Godzilla

By Brian Eggert |

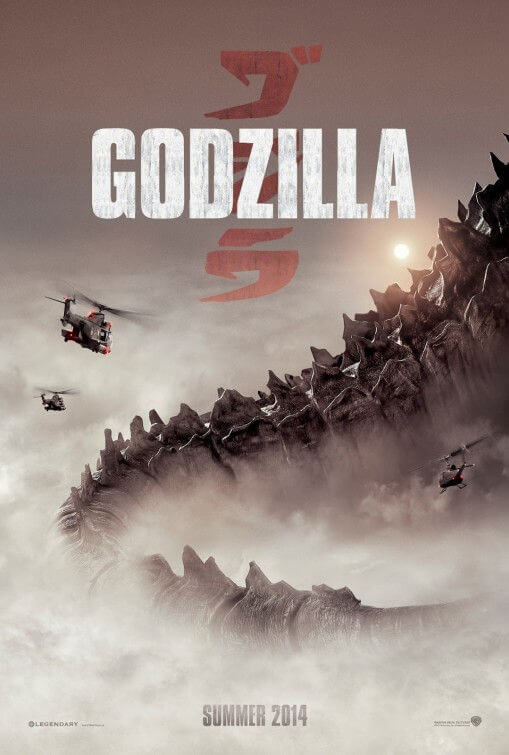

Taking a cue from Skyfall, which paid homage to its franchise’s 50-year history by compiling its standard formulas into a singular yet artful amalgamation, Warner Bros. and Legendary Pictures celebrate the 60th anniversary of the King of All Monsters with Godzilla. And like the last James Bond film, the new production embraces the best aspects of Godzilla’s various interpretations and long history, beginning with Toho Films’ 1954 original Gojira, director Ishiro Honda’s sobering disaster film steeped in an anti-nuclear commentary. Along with hints of environmentalism similar to those in Honda’s original, the franchise reboot also honors the lighter “versus” sequels, such as Godzilla vs. Mothra (1964) and Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla (1974), which put Godzilla against other large kaiju (the Japanese term for colossal monsters) in epic, and corny, city-destroying battles. Following that strain, the new film also reestablishes Godzilla as a heroic figure, even though it also contains a degree of disaster movie sensationalism borrowed from Roland Emmerich and Dean Devlin’s notoriously dim remake from 1998, all but disowned by Godzilla enthusiasts and Toho alike.

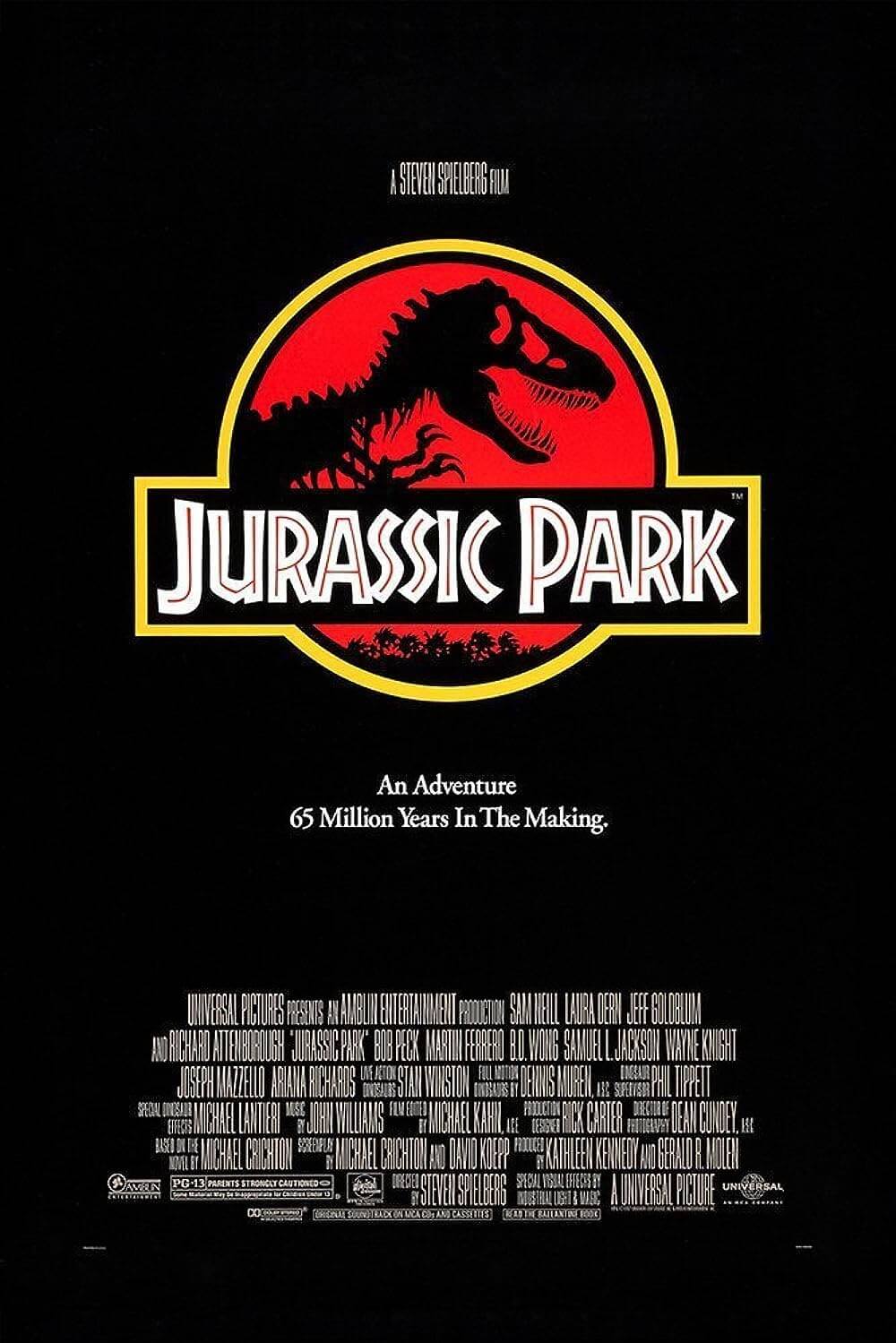

At the helm is British filmmaker Gareth Edwards, whose $250,000 indie debut Monsters was an underdeveloped romance set against a landscape ridden by giant alien creatures. Godzilla feels like an extension of Monsters, only on a grander, blockbuster scale, and a price tag of $160 million. Edwards also taps into a number of obvious influences, but rather than follow his predecessors in the Godzilla franchise or even Guillermo del Toro’s recent kaiju disappointment Pacific Rim, the director draws from Steven Spielberg—specifically Spielberg’s Jurassic Park and, even more, War of the Worlds. Indeed, much like Spielberg’s underrated H.G. Wells’ adaptation from 2005, Godzilla‘s screenplay (story by David Callaham and writing by Max Borenstein) centers on several characters scrambling to survive amid fantastical dangers, the gravity of their human drama meant to outweigh the sheer size of the monster movie thrills. Unlike War of the Worlds, however, this film’s characters lack the flaws, humor, vulnerability, and family dynamics that would otherwise make the material stirring. Still, Edwards delivers enough raw spectacle to make Godzilla entertaining.

After an opening credits sequence that shows vintage footage of nuclear bomb testing designed to kill Godzilla, the film jumps to 1999, when in the Philippines, a mining operation discovers an enormous skeleton underground. Japanese scientist Dr. Serizawa (Ken Watanabe) and his assistant Dr. Graham (Sally Hawkins, underused) find something else nearby—a huge cocoon-like thing that’s hatched, and whatever was inside has crept into the ocean. Meanwhile, at a nearby Japanese nuclear power plant, scientist couple Joe and Sandra (Bryan Cranston and Juliette Binoche) try to prevent a meltdown brought about by mysterious tremors that soon reduce the entire plant to rubble. Cut to fifteen years later. Joe has fanatically researched for what he insists is a government cover-up of the plant disaster and implores his only son, Ford (Aaron Taylor-Johnson), a bomb disarmer for the U.S. Navy, to assist him in exposing the conspiracy at the former plant’s location—now a quarantine zone. What they find is a top-secret station feeding radiation to the cocoon-thing, which soon hatches into a gigantic, flying, triangle-headed insect with electromagnetic powers (not unlike Gyaos, a popular rival of Godzilla’s turtle-shaped cousin, Gamera).

Dubbed M.U.T.O. (Massive Unidentified Terrestrial Organism), the creature wreaks havoc by seeking out radiation foodstuff (missiles, submarines, etc.). The American military, headed by David Strathairn’s dry admiral character, attempts to destroy this radiation-eating baddie, albeit ineffectually. At the same time, Godzilla stirs in the ocean, an “alpha predator” of ancient origin, seemingly awakened by the M.U.T.O.-caused ruckus and impelled to “restore balance to nature”—both assumptions in the monster’s motivations and scientific logic made by Dr. Serizawa. Hunting down the M.U.T.O. and invariably misunderstood by the narrow-minded men in charge, Godzilla doesn’t appear onscreen until well into the second act, looking thicker than earlier versions, but bipedal, and downright ferocious. Meanwhile, the film quickly disposes of the one human character in whom we’ve become emotionally invested, Joe, and with his loss, and the desirable presence of Cranston, we’re left with an ensemble of uninteresting and one-dimensional humans. Most of the action from here on out follows Ford, who tries to get home to his concerned wife (Elizabeth Olsen), but given his handy background in bomb disarmament, he is drawn into a world-saving mission.

Much like Monsters, Edwards saves his creature money shots until the awe-inspiring finale. During the middle of the film, when we’re most desperate to get a good look at the kaiju, the director toys with his audience by savoring Spielbergian moments in true Jurassic Park form. The first major battle between M.U.T.O. and Godzilla is glimpsed on a television newscast watched with wonder by Ford’s son (Carson Bolde). Another scene shows the water recoiling from the Hawaiian shoreline as Godzilla emerges from the sea, this caught by a young girl who notices before anyone else. On the Golden Gate Bridge, a school bus driver wipes the fog away to spy Godzilla rising from the bay. However Spielberg-inspired these individual shots may be, and however much they suggest the focus of Godzilla is human more than monster, the human characters, though portrayed by an incredibly interesting ensemble, prove so uninteresting that the long delay in the monster showdown does the film a disservice.

Then again, the last 30 minutes of Godzilla are so marvelously exciting that by this point, the dull humans, and the film’s generally slow-build, are secondary to the pure blockbuster showmanship anyway. Several larger-than-life scenes are also elegant and indescribably perfect: an electromagnetic pulse forces jets to fall from the clouds; airliners explode in a domino-effect cascade on a Hawaiian tarmac; paratroopers descend into the monsters’ battle, their fall ominously set to Alexandre Desplat’s score (which borrows a haunting riff from 2001: A Space Odyssey for this scene). None is more exhilarating than the final confrontation between Godzilla and a M.U.T.O. pair, a sequence that will undoubtedly incite cheers by the end. All of these moments are gorgeously realized in top-notch CGI and set in Edwards’ color palate of muted browns and grays to reflect the film’s overall humorless tone. To be sure, the level of seriousness maintained by Godzilla is admirable, giving the production respectability no Godzilla film has had since Honda’s original. But the film’s lasting impact, or lack thereof, resides in the human characters and their shortage of interesting qualities.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review