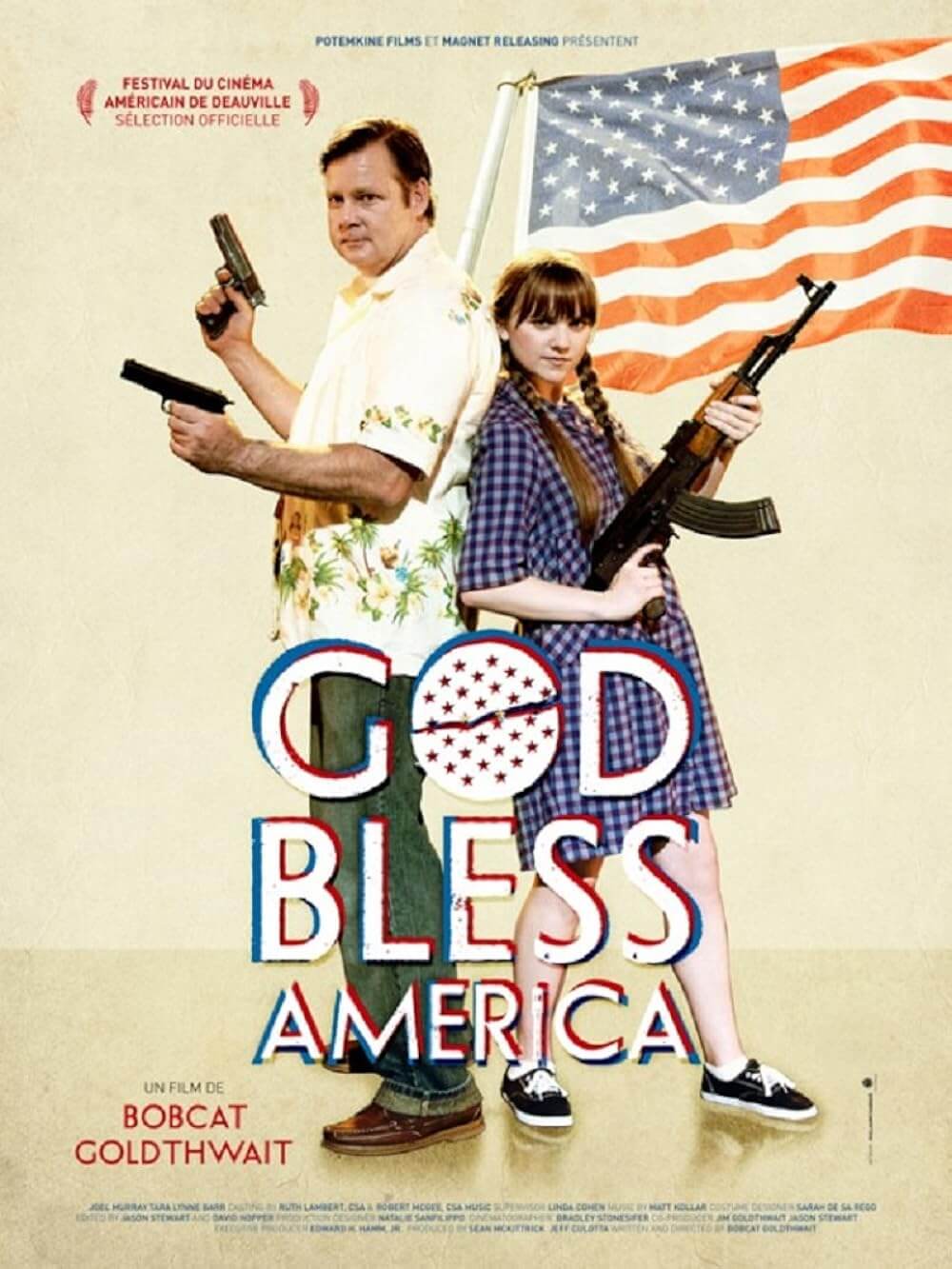

God Bless America

By Brian Eggert |

In Bobcat Goldthwait’s wonderful rant-of-a-film God Bless America, the writer-director’s two heroes take aim at America’s very worst and pull the trigger. This is not a metaphor. A mad-as-hell-and-can’t-take-it-anymore office worker and spunky teenage girl arm themselves and target morally corrupt pop-culture icons, reality TV stars who debase themselves for ratings, and self-important cell phone gabbers, and then gun them down for an unrivaled sense of wish-fulfillment. At once unnerving and bitingly hilarious, Goldthwait’s script—fuelled by rage over America’s cultural downturn as of late, a sentiment no doubt shared by many in his audience—douses acid in the face of our culture and watches it fry (this is a metaphor). For a comedian whose black comedies involve subjects like dysfunctional clowns, autoerotic asphyxiation, and experimentation with bestiality, none boasts satire darker, more confronting, or more consequential than this.

A sequence where everyman anti-hero Frank, played by Joel Murray, channel surfs on late-night television sums up everything that has infuriated Goldthwait to make this film. He sees loud commercials for energy drinks, crass political commentators, and just plain bad behavior. In one of these segments, there’s an American Idol spoof where a young hopeful fails miserably, and it turns into a national story; this William Hung-esque figure becomes a hot topic overnight and supplies the butt of endless jokes at water coolers and on various news outlets. Frank observes that people can no longer have real conversations: “Nobody talks about anything anymore; they just regurgitate everything they see on TV.” When Frank loses his job, finds out he’s dying of a brain tumor, and gives up on seeing his spoiled daughter all in the span of a day, he resolves to take his gun and shoot down a loathsome reality TV brat who berated her parents when they didn’t buy her the correct model car on her sweet sixteen.

After his first kill, Frank plans to commit suicide, but he’s interrupted by his unlikely future partner, a spirited 16-year old, Roxy (Tara Lynne Barr), who shares Frank’s disdain for society’s mass intellectual impairment. Roxy proposes a killing spree where they target only those who “deserve to die,” like people who use up two parking spaces or aggressive Tea Partiers. My favorite among their list of despised: People who say “literally” to exaggerate a figurative statement (such as “My heart was literally beating out of my chest”). Know the difference. In voiceover, Frank admits his behavior isn’t normal; killing people who bother you isn’t condoned by this film, nor recommended by anyone involved. To be sure, Frank is a curiously moral figure, killings aside. For example, when Roxy asks if he thinks she’s cute, he refuses to answer on moral grounds. He’s not a pedophile, and, though he develops a close platonic bond with Roxy, he despises how culture has taught men to objectify young women’s bodies.

Another, somewhat unrelated film kept creeping into my head during this one: George A. Romero’s Dawn of the Dead, a satire of the highest order that paints symbolic strokes of bloody red. Both films employ a scenario populated by extreme characters and circumstances, and they use these elements to expound a scathing belief about and reflection of our culture. Violent acts in God Bless America transform what would otherwise amount to an extended sardonic tirade. Violence becomes a mode of expression through which the audience finds catharsis, but also helps punctuate our comparable feelings toward Frank and Roxy’s targets. And yet, this film is not absent of tender moments between the protagonists, making it an oddly touching killer road trip movie.

The danger in using violence in a movie like this rests in audiences missing the point, because Goldthwait runs the risk of viewers being too shocked or appalled by the violence on display to see his completely valid point. In an early scene, Frank laments about the neighbors on the other side of his paper-thin wall, the couple’s arguing, and their endlessly crying baby. “They’re incapable of comprehending that their actions affect other people,” Frank observes, unable to sleep. Then, he drifts off into a reverie where he enters their home, guns down the father, and then shoots the crying baby, showering its mother in its blood. Any viewer who still hasn’t gotten what Goldthwait is going for by this point will probably be lost as the film continues. The film’s most satisfying scene will resonate with frequent moviegoers. Frank and Roxy take their seats in an arthouse theater showing a documentary about wartime atrocities. A twentysomething double date sits behind them, gabbing away and playing on their cell phones. You can predict what happens next.

Intentional references to Bonnie and Clyde, Taxi Driver, Natural Born Killers, and Jackie Brown aside, Goldthwait’s script finds a unique, angry voice that’s oddly relatable, in that many of us will watch Frank and Roxy make lists of their annoyances and socially inconsiderate types and passionately agree. Using satiric violence and frequent verbal soapboxing, Goldthwait’s philosophy bears ugly truths about American culture that many embrace as normality, but that’s the problem. God Bless America cries out for a change in a funny, shocking, unflinching manner and probes the depths of what it means to be a black comedy. It was made to shake viewers out of their complacency. Anyone who endures the experience can’t help but notice how accurate an assessment Goldthwait has made. When you return to work the next day, and your coworkers begin to discuss what happened on American Idol, first you’ll cringe with disgust, and then you’ll realize just how much you agree with what Goldthwait has to say.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review