Glass

By Brian Eggert |

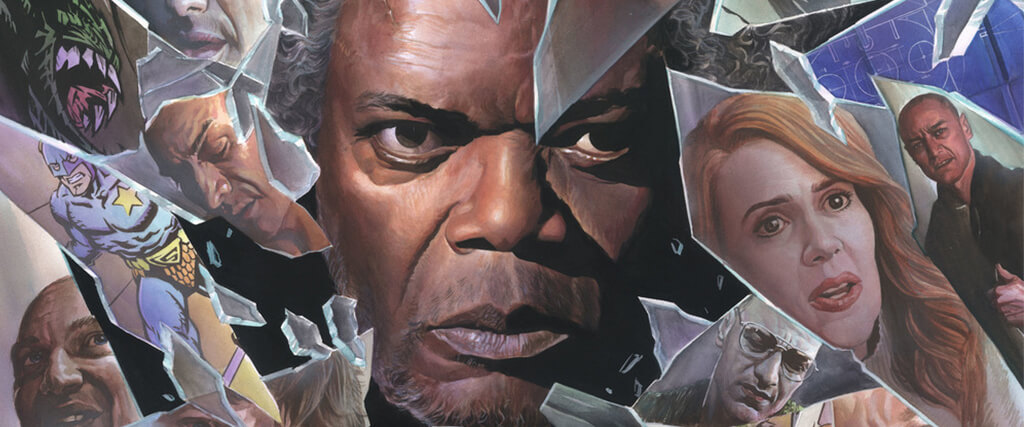

M. Night Shyamalan completes his trilogy of realistic comic book stories with Glass, the final chapter in a series that began with Unbreakable (2000) and continued, seventeen years later and much to the surprise of audiences, with Split. Taking the whole trilogy as a narrative that carries through each entry and concludes here, it’s not surprising that the writer-director punctuates his finale with a Shyamalan-level twist. But as those familiar with his body of work know, his penchant for radical shifts in the third act sometimes ruin an otherwise intriguing concept. Glass is similar to the worst films in Shyamalan’s career—The Village (2004), Lady in the Water (2006), and The Happening (2008)—in that it executes a fascinating concept with such clumsiness, approaching the idea from such a misguided angle, that the viewer can only respond with incredulity and bafflement.

Shyamalan’s career has been a rollercoaster both creatively and at the box-office, and Glass signals another steep descent. His last film, Split, was an unexpected hit that made $278 million in receipts internationally. However, it arrived after a long line of creative and financial failures that signaled the plummet of the once-promising director from hits like The Sixth Sense (1998) and Signs (2002) into underperforming duds like The Last Airbender (2010) and After Earth (2013). After hitting a low point, Shyamalan climbed back up by demonstrating he could make a sizable profit on a microbudgeted “found footage” horror yarn, The Visit (2015). Perhaps out of necessity, his writing also became less self-conscious, his filmmaking less grandiose. Watching his next cheapie, Split, you see a filmmaker who excels because he’s forced to make creative, cost-conscious decisions. But its unexpected success seems to have gone to Shyamalan’s head; with Glass, he indulges himself in ways that do a disservice to the material and its fans.

At the end of Split, Shyamalan connected his Hitchcockian thriller, about James McAvoy’s multiple-personalitied psycho The Horde, to the same universe as Unbreakable, where Bruce Willis’ strongman David Dunn was a makeshift superhero opposite Samuel L. Jackson’s evil, physically fragile mastermind Mr. Glass. The title of Glass misguides the viewer into thinking it’s Jackson’s show. Alas, Mr. Glass spends the bulk of the film tranquilized in a mental institution, where he’s been since 2000, until Dunn and The Horde join him. Early in the film, Dunn, wanted for his illegal vigilantism, confronts The Horde, who has left a sizeable body count of dead teenage girls in his wake, before the authorities capture them both. Together, all three will receive treatment from Dr. Ellie Staple (Sarah Paulsen), a specialist in a very particular field: superhero-related delusions of grandeur.

The main thrust of Glass, then, is Dr. Staple’s attempt to disprove what we already know to be true—these three have super-powers that resemble comic book characters. She argues that there’s a scientific explanation for their abilities (“damaged frontal lobes”) and that each man has conflated their powers in their own minds. And while Dr. Staple admits their talents are perhaps extraordinary, she splits hairs when she refuses to acknowledge they are super, which seems like a meaningless distinction. After all, why, if she believes that Dunn’s super-strength is an exaggeration, does she bother to seal him in a metal room with an expensive-looking high-pressure sprinkler system that will expose him to his weakness, water, which she claims is another delusion? Why not just lock him in a padded cell? Moreover, she claims to have been given three days to convince Dunn and the others that their abilities are part of an elaborate delusion. By whom, and why only three days? It all makes sense by the end, but not without dragging the viewer through two hours of illogical scenarios.

Rather than create dramatic tension by telling a story with, say, a protagonist who has a conflict to overcome, Shyamalan uses a device only a screenwriter could conceive. Dr. Staple introduces the idea that there aren’t actual super-people and gives each of her prisoners something to prove to the world. This feels out of character for Dunn, who fights crime in the shadows, as well as The Horde, whose personalities are too busy contending with “The Beast” to care about how the world views his superness. By contrast, Glass’ raison d’être is to convince everyone around him that he’s playing a part in a real-life comic book scenario. Most of his dialogue consists of underscoring how their lives resemble comic book tropes, which lends a self-consciousness to the proceedings that renders it dramatically inert. Indeed, the setup is a lousy conceit on Shyamalan’s part as, besides being full of plot holes, it refuses to embrace what might have been a dazzling showdown.

Rather than create dramatic tension by telling a story with, say, a protagonist who has a conflict to overcome, Shyamalan uses a device only a screenwriter could conceive. Dr. Staple introduces the idea that there aren’t actual super-people and gives each of her prisoners something to prove to the world. This feels out of character for Dunn, who fights crime in the shadows, as well as The Horde, whose personalities are too busy contending with “The Beast” to care about how the world views his superness. By contrast, Glass’ raison d’être is to convince everyone around him that he’s playing a part in a real-life comic book scenario. Most of his dialogue consists of underscoring how their lives resemble comic book tropes, which lends a self-consciousness to the proceedings that renders it dramatically inert. Indeed, the setup is a lousy conceit on Shyamalan’s part as, besides being full of plot holes, it refuses to embrace what might have been a dazzling showdown.

On the sidelines, Glass’ mother (Charlayne Woodard, under laughably bad old-age makeup because she’s five years younger than Jackson) confronts Dr. Staple about her methods. Dunn’s son Joseph (Spencer Treat Clark), whose only super-ability is to perform basic Google searches, tries to convince the hospital to release his dad. And The Horde’s kidnapping victim from Split, Casey (Anya Taylor-Joy), seems to have succumbed to Stockholm syndrome. Casey, apparently unfazed by The Horde having slaughtered several other teenage girls, tries to help Dr. Staple reassemble the killer’s fractured mind. Throughout the proceedings, Willis is checked-out, not that it matters; his character isn’t the focus. McAvoy, once again, steals the show. But the character’s routine of alternating amid a dozen-or-so personalities has lost its novelty and becomes tedious.

Shyamalan’s writing is usually the problem with his work, whereas his use of form often shines. But on Glass, the director seems strapped by his $20 million budget, which isn’t much for a well-cast superhero film. Instead of necessity being the mother of invention, the limited funds expose how Shyamalan has little idea how to shoot an action scene. Willis and McAvoy wear body-mounted cameras that face them during Dunn and The Horde’s showdowns, so we see them react to the fight, but we don’t get a clear view of the battle itself. In another cost-cutting measure, there are several scenes of a very vascular McAvoy disrobing, roaring, and then attacking his opponent just out of view. Shyamalan, cinematographer Mike Gioulakis, and the team of editors may achieve a well-framed or arranged moment or two, but overall, they deliver a patchy experience devoid of narrative rhythm. It’s all set to an annoying score of high-pitched strings by West Dylan Thordson.

If Split was Shyamalan’s ode to Psycho (1960), then Glass pays homage to the dreadful end of that film where a doctor explains the killer’s motivations in dumbed-down Freudian terms. Between Staple’s psychobabble and Glass’ endless comparisons of real-life and comic books, Shyamalan’s script dwells on what he thinks worked best about the earlier films: the notion of comic books imitating real superheroes, and McAvoy’s multilayered performance. But he’s got it all wrong. The best part of Unbreakable was watching an average Joe realize he’s a hero, and the best part of Split was the director’s clear Hitchockian inspiration. It’s all punctuated with an insulting finale. By the end of Glass, Shyamalan’s signature twist results in a complete waste of the characters he so meticulously established in the trilogy’s earlier films, while resting on a scene that’s laughably stupid and entirely too optimistic about humanity’s lack of skepticism. Glass is among Shyamalan’s worst films, and it’s all the more disappointing because by association it spoils two of his best.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review