Reader's Choice

Giant

By Brian Eggert |

Giant is a film with an identity crisis. Made in the tradition of sweeping postwar epics designed to draw people away from their television sets and back into cinemas, the massive production was mounted by director George Stevens and resulted in a landmark of Hollywood prestige filmmaking, complete with a huge price tag, legendary stars of the screen, and a three-hour-plus runtime. Embedded into the melodrama about three generations of a Texas family are deconstructions of class, gender, social change, and racial intolerance. Following A Place in the Sun (1951) and Shane (1953), Stevens’ equally critical portraits of American sensibilities, Giant is the director’s commentary on a distinctly Texan culture of excess, typified by its exclusively nouveau riche upper class. The film’s willingness to critique the larger-than-life Texan identity as a metaphor for all of America is contradicted by the draw of its own production value, which at the time was called Texas’ own Gone with the Wind (1939). And like that film, Giant has not aged well in its rudimentary treatment of race, female agency, and inclusivity. It denounces racism, yet its denunciations unintentionally creates division; it questions the patriarchy, yet its central female character ultimately bows to her husband’s wishes. To watch Giant is to experience a series of contradictions, albethey in an impressive package.

As observed by Stevens biographer Marilyn Ann Moss, Giant was released during an era of social change for women and people of color. It was a period of consumerism, “where big was better and where women had influential buying power.” After the Second World War, a growing middle class flourished alongside the booming United States economy. Nearly half of all families in the country belonged to the middle class, the consumer class. And within the average American household of the 1950s, women served as the primary shoppers. Women, therefore, played an essential role in America’s consumer marketplace, and manufacturers went to significant lengths to appease this demographic. Given the new value of women as postwar consumers, their power in the household grew, just as products themselves had grown. Bigger homes, bigger cars, and bigger families indicated success and status, and a sense of ownership over these items often belonged to the women who picked them out or raised them.

Along with the new importance given to women, other disenfranchised groups were rising up and declaring a voice for themselves. The Civil Rights movement was underway, as African Americans leaders called for equality, school segregation had just ended, and Rosa Parks had refused to give up her seat on a bus. More pertinent to Giant, relations between Mexico and the United States intensified after President Eisenhower’s immigration control program took the name of a racial epithet: “Operation Wetback” led to the arrest and deportation of more than 1.1 million Latin Americans in 1954 alone, some of them U.S. citizens. In many cases, the workers had their personal property seized and were separated from their families. The initiative resulted in an outcry for social justice among Mexicans working in the U.S. under the Bracero program—an initiative between the U.S. and Mexico during the Second World War that ensured immigrant workers would receive fair conditions as farmers while the U.S. needed them. After the war, however, the U.S. government determined that the presence of undocumented Latin Americans was no longer necessary, and mass deportations ensued.

It was during these times of emboldened female importance, bigger-is-better consumerism, and public debates about racial equality that Giant was published. Edna Ferber’s story, originally serialized in issues of Ladies’ Home Journal before its 1952 publication as a novel, tells the story of a Texas rancher who meets his match in a Maryland socialite. She questions his male-dominated and prejudiced way of life, and he’s slow to change. Ferber’s book and its portrayal of Texas culture made its journey to the screen on a rockier path than most best-sellers. It depicts Texans as racist, corrupt, laughably simple-minded, and exploitative of Mexican workers. Many in Texas took offense, whereas Ferber’s target was America on the whole. As one could imagine, many studios wanted nothing to do with the debate about the book. But Stevens was drawn to the controversy around the best-selling novel, its built-in audience, and its portrait of a complicated marriage. Together with producer Henry Ginsberg, Steven launched his own production company in 1953, and they used appropriately named Giant Productions to shop the project to various Hollywood studios. Fox passed due to the rumors of a troubled production on Stevens’ yet-unreleased Shane—a mistake, since Shane would become a huge success. But Warner Bros. saw the obvious potential in Giant and signed a contract to finance, distribute, and market the film.

It was during these times of emboldened female importance, bigger-is-better consumerism, and public debates about racial equality that Giant was published. Edna Ferber’s story, originally serialized in issues of Ladies’ Home Journal before its 1952 publication as a novel, tells the story of a Texas rancher who meets his match in a Maryland socialite. She questions his male-dominated and prejudiced way of life, and he’s slow to change. Ferber’s book and its portrayal of Texas culture made its journey to the screen on a rockier path than most best-sellers. It depicts Texans as racist, corrupt, laughably simple-minded, and exploitative of Mexican workers. Many in Texas took offense, whereas Ferber’s target was America on the whole. As one could imagine, many studios wanted nothing to do with the debate about the book. But Stevens was drawn to the controversy around the best-selling novel, its built-in audience, and its portrait of a complicated marriage. Together with producer Henry Ginsberg, Steven launched his own production company in 1953, and they used appropriately named Giant Productions to shop the project to various Hollywood studios. Fox passed due to the rumors of a troubled production on Stevens’ yet-unreleased Shane—a mistake, since Shane would become a huge success. But Warner Bros. saw the obvious potential in Giant and signed a contract to finance, distribute, and market the film.

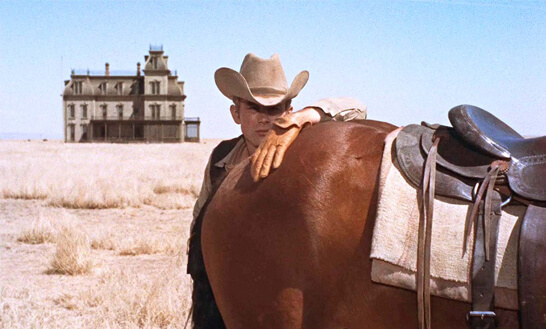

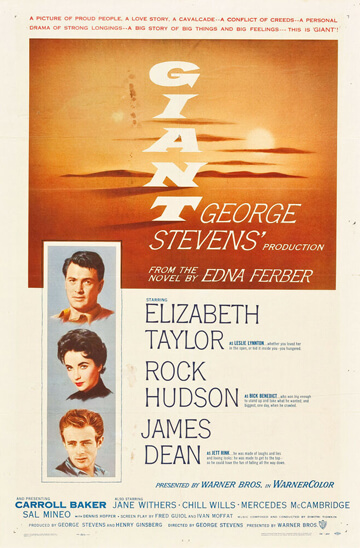

As was often the case with Stevens’ postwar films, the director’s production was a drawn-out process that involved multiple scripts, a highly publicized casting call, and a longer-than-usual editing process. Ferber originally set out to adapt her book for the screen, but she clashed with Stevens over several alterations he demanded, and she was eventually replaced by Fred Guiol and Ivan Moffat. For the cast, Stevens reached out to the era’s most famous stars. Grace Kelly, Rita Hayworth, and Olivia de Havilland were considered for the female lead, Leslie Benedict, but Elizabeth Taylor took the role. William Holden and Robert Mitchum were in the running for the male lead, but along with his sheer size, Rock Hudson had demonstrated his range in a series of collaborations with Douglas Sirk, and he was cast as Jordan “Bick” Benedict. For the young-upstart-turned-drunken-industrialist Jett Rink, Stevens thought about Montgomery Clift, Van Heflin, and Anthony Quinn, but James Dean had impressed the director with his performance in Rebel without a Cause (1955). Dean made his final screen appearance in Giant before dying in an auto-racing accident in 1955, just after completing his scenes.

Giant went before cameras in May 1955, and the director quickly realized that the initial budget estimate of $1.5 million was unrealistic. After a series of delays and unexpected costs resulting from Stevens’ perfectionist style of shooting, the production exceeded the allotted 70-day shooting schedule and the budget ballooned to over $5 million. Jack Warner, head of production at Warner Bros., was ready to take over the production himself. But before any actions could be taken, Warner received universally positive feedback from an audience test screening. Given such overwhelming positivity, Stevens was allowed to continue working, and he spent the next year editing the picture down to a three-hour-and-seventeen-minute runtime. He originally intended a roadshow edition, complete with an intermission. The final cut, however, was released without a break. This duress on the human bladder was perhaps why, among the almost universally positive reviews from the period, so many critics complained about the protracted runtime. Regardless, Stevens delivered one of Warner’s most successful pictures of the era; it was a huge box-office earner, and it nabbed Stevens an Oscar for Best Director, along with nine other Academy Award nominations for the cast and crew of Giant.

The story opens as the towering bachelor “Bick” Benedict arrives in Maryland to purchase an unruly stallion, and he can’t take his eyes off of the seller’s privileged daughter, Leslie. “That sure is a beautiful animal,” says Bick of Leslie, when he’s supposed to be looking at a horse. Before long, Bick marries the independent-minded Leslie and delivers her to Reata, his 595,000-acre cattle ranch in Texas, where his family has long been king of the hill. But Leslie quickly rustles the feathers of her husband’s rough, traditionalist sister, Luz (Mercedes McCambridge). When Luz dies in a horse-riding accident, she leaves a plot of land to their resentful ranch hand Jett, who refuses to sell the land back to Bick for a paltry $1,200 payday. Over time, Jett works the inherited land himself and strikes oil, and he becomes the millionaire owner of the absurdly named “Jetexas,” if only out of spite for Bick and the entire Benedict name. Times change as three decades pass. The state’s chief product shifts from cattle to oil. Leslie and Bick have heated arguments about matters of race and the roles of women in the household, most of which are resolved with make-up sex, resulting in children. Eventually, Bick must accept change and face his prejudices when his son (Dennis Hopper) resolves to break from tradition—he wants to study animal husbandry over ranching and marries a Mexican-American woman.

The story opens as the towering bachelor “Bick” Benedict arrives in Maryland to purchase an unruly stallion, and he can’t take his eyes off of the seller’s privileged daughter, Leslie. “That sure is a beautiful animal,” says Bick of Leslie, when he’s supposed to be looking at a horse. Before long, Bick marries the independent-minded Leslie and delivers her to Reata, his 595,000-acre cattle ranch in Texas, where his family has long been king of the hill. But Leslie quickly rustles the feathers of her husband’s rough, traditionalist sister, Luz (Mercedes McCambridge). When Luz dies in a horse-riding accident, she leaves a plot of land to their resentful ranch hand Jett, who refuses to sell the land back to Bick for a paltry $1,200 payday. Over time, Jett works the inherited land himself and strikes oil, and he becomes the millionaire owner of the absurdly named “Jetexas,” if only out of spite for Bick and the entire Benedict name. Times change as three decades pass. The state’s chief product shifts from cattle to oil. Leslie and Bick have heated arguments about matters of race and the roles of women in the household, most of which are resolved with make-up sex, resulting in children. Eventually, Bick must accept change and face his prejudices when his son (Dennis Hopper) resolves to break from tradition—he wants to study animal husbandry over ranching and marries a Mexican-American woman.

Just a few drinks and murders shy of Written on the Wind (1956), Giant is a melodrama in the traditional, non-pejorative sense, wherein class conflicts are dramatized with heightened emotions and an escalating theatricality. (The setup was undoubtedly an inspiration for the prime-time soap opera Dallas.) Leading the wonderful cast, Hudson and Taylor beam with the Texas-sized emotions on display. However troublesome his character may be, Hudson embodies the manliness and intimidating power of Bick—an actor with less charisma and charm would have reduced Bick to a mere bigot. Taylor’s performance is strong, at least in the first half when she has more to do, before her character settles into her assigned role as wife and mother in the second half. Dean’s odd mannerisms and volatile onscreen presence end up being the most interesting aspect of the film, as Jett has a significant digression. Jett becomes the thing he hates, an elitist, and he knows it, which is why he drinks and remains in an almost one-sided competition with Bick. Even so, other characters label him as “a great Texan, an outstanding American… a man”—and this is after he builds a hotel and orders his staff not to admit persons of color. Giant is particularly good at critiquing what makes a man and an American by way of the stereotypical Texan of this era: a white, macho male who’s prejudiced, materialistic, and violent.

When the production of Giant was first announced, the League for Spanish Speaking People reached out to Stevens, hoping to ensure a fair and honest representation that avoided any “derision, ridicule or criticism to the eight million Americans of Mexican ancestry.” And while Giant seeks to recognize the humanity of its Latin American characters, it never portrays them as anything but outsiders to the central Benedict clan. They are an integral part of Texas, but they have been relegated to an Other. Even though Ferber’s story boasts a social consciousness, Stevens, as usual, was swept up by the relationships in the film, resulting in a film of mixed messages. This is a pattern in Stevens’ work. His comedy Woman of the Year (1942) found the ambitious Katherine Hepburn rallying against traditional roles for women, but ultimately sacrificing her professional independence to become Spencer Tracy’s “good wife.” Or consider A Place in the Sun, whose source material critiqued the hollowness of American capitalism and ambition—but Stevens rendered those themes inert when he cast stars Montgomery Clift and Elizabeth Taylor, whose tabloid romance overshadowed the film’s commentary.

The well-meaning but finally misguided treatment of race in Giant begins when Leslie questions Bick about Texas’ history of stealing land from Mexico, or his town’s treatment of the local Latin American citizens. Don’t make a fuss over “those people,” Bick tells his wife. “You’re a Texan now.” Leslie disapproves when Bick’s sister claims that Mexicans “sit on their honkers all day,” or when she’s warned not to be around “the wrong people.” And while she’s quick to point out the Texan prejudices against Latin Americans, neither she nor the film adequately acknowledges her own family’s treatment of African Americans, such as their black servant or grotesque lawn jockey. By the end, Bick seemingly redeems his racist behavior when he confronts a diner owner who refuses to serve a Latino family (played by actors who appear to be in brownface). Bick receives a beating as his atonement. Afterward, Leslie calls him out on his lifelong racism, especially in the wake of their two grandchildren, one white and the other Chicano. Just a few minutes after atoning for his racism in the diner, Bick regards his grandchild and says, ”So help me, but he looks like little wetback.” Though Bick has learned very little, Leslie lovingly dismisses his stubborn racism. “Do you want to know something?” she tells him. “I think you’re great. Don’t ask me why. Some things are difficult to explain.” And at this point, the audience is thoroughly confused about where Giant stands about its characters and their racist behavior.

The well-meaning but finally misguided treatment of race in Giant begins when Leslie questions Bick about Texas’ history of stealing land from Mexico, or his town’s treatment of the local Latin American citizens. Don’t make a fuss over “those people,” Bick tells his wife. “You’re a Texan now.” Leslie disapproves when Bick’s sister claims that Mexicans “sit on their honkers all day,” or when she’s warned not to be around “the wrong people.” And while she’s quick to point out the Texan prejudices against Latin Americans, neither she nor the film adequately acknowledges her own family’s treatment of African Americans, such as their black servant or grotesque lawn jockey. By the end, Bick seemingly redeems his racist behavior when he confronts a diner owner who refuses to serve a Latino family (played by actors who appear to be in brownface). Bick receives a beating as his atonement. Afterward, Leslie calls him out on his lifelong racism, especially in the wake of their two grandchildren, one white and the other Chicano. Just a few minutes after atoning for his racism in the diner, Bick regards his grandchild and says, ”So help me, but he looks like little wetback.” Though Bick has learned very little, Leslie lovingly dismisses his stubborn racism. “Do you want to know something?” she tells him. “I think you’re great. Don’t ask me why. Some things are difficult to explain.” And at this point, the audience is thoroughly confused about where Giant stands about its characters and their racist behavior.

In his analysis of race in Giant, scholar Rafael Pérez-Torres wrote the film “gives voice to a new America, one that struggles with discourses of inclusion and pluralistic liberalism.” This is never more apparent than the final shot of the Benedict family future: the grandchildren. Bick and Leslie’s son Jordie has fathered a Chicano child with his Mexican wife, while their daughter Judy has given birth to a Caucasian son with her white husband. The final image shows Judy’s Caucasian child with a white lamb behind him, whereas a black sheep stands behind Jordie’s Chicano child. The two share the same crib, which suggests that we’re all human beings living in the same world, and therefore we should all treat each other with equality. But the animals in the image have another association. A white lamb was chosen for the white child and the black sheep for the multiracial child, and the animals create a negative racial commentary. The idiom “black sheep,” of course, has an association with undesirable outsiders, whereas a white lamb often represents purity and innocence. By framing the two children together in this way, Stevens’ unintended metaphor reinforces generalizations based on race and underscores difference rather than promoting equality. As Moss notes, “Despite Stevens’s liberal politics and humanistic values, Giant’s depiction of racial tensions—and what critics like to call Leslie’s feminist views—have more to do with their contribution to the story’s dramatic tension than anything else.”

Indeed, Bick never becomes a tolerant, modern man who stops seeing Latin Americans as the Other or accepts his wife as his equal. Even though Leslie is a strong-minded, independent woman, she never achieves any real agency. From the first moment she appears onscreen, her presence is linked with that of a wild stallion that must be tamed, and Bick ultimately tames her, even if he must endure a few bucks and kicks along the way. Watch the sequence early in the film where Leslie attempts to talk politics with the men. “Don’t you go worrying your pretty little head about politics,” they tell her, much to her incredulity. Leslie explodes at Bick in front of everyone in a satisfying bout of feminist rage: “You ought to be wearing leopard skins and carrying clubs!” Later that evening, after a passionate argument, all is forgotten because of the essential child-making dynamic of their relationship: make-up sex. Leslie’s protests against Bick’s white, male-dominated sense of superiority represent a satisfying defiance, but the film creates a correlation between her disapprovals and a mare in heat, underlined by the association between Leslie and the stallion Bick arranged to buy in the film’s opening. Her protestations against Bick’s behavior are calmed when Bick breaks her in through intercourse, and as long as they keep having children, she falls into line and does not question her husband. And so, Bick has no need to change. The times change, as do the subsequent generations, but Bick never does.

Similar to Stevens’ other films, the humanist message of Giant results in a confused and uncommitted social stance, evidenced in how the film ungainly blends the social drama with melodrama, two strains that work separate from one another instead of in tandem—the former is focused on the lessons learned (or not), the latter on the emotions felt. Even so, Giant remains a superb example of the lasting allure of spectacles in the Western genre. Massive productions such as Duel in the Sun (1946), Red River (1948), The Searchers (1956), and The Big Country (1958) each dealt with issues of race, authority, and xenophobia to some extent, while also employing a visual scope worthy of their expansive settings. Watching Hudson, Taylor, and especially Dean in such an exquisite backdrop has its basic thrills. But any extended thought about what Giant wants to say or how it communicates its social consciousness to the viewer through narrative and story results in a confrontation with its unwieldy symbolism and the characteristic overdirection by Stevens.

(Editor’s Note: This review was commissioned on Patreon. Thanks for your suggestion, Rose!)

(Updated November 7, 2020, to reflect correct acreage.)

Bibliography:

Moss, Marilyn Ann. Giant: George Stevens, A Life on Film. Terrace Books, 2015.

Pérez-Torres, Rafael. Mestizaje: Critical Uses of Race in Chicano Culture. University of Minnesota Press, 2006.

Rosenfield, John. “Texas-Size Giant.” Southwest Review, vol. 41, no. 4, 1956, pp. 370–379.

Worden, Daniel. “Fossil-Fuel Futurity: Oil in ‘Giant.’” Journal of American Studies, vol. 46, no. 2, 2012, pp. 441–460.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review