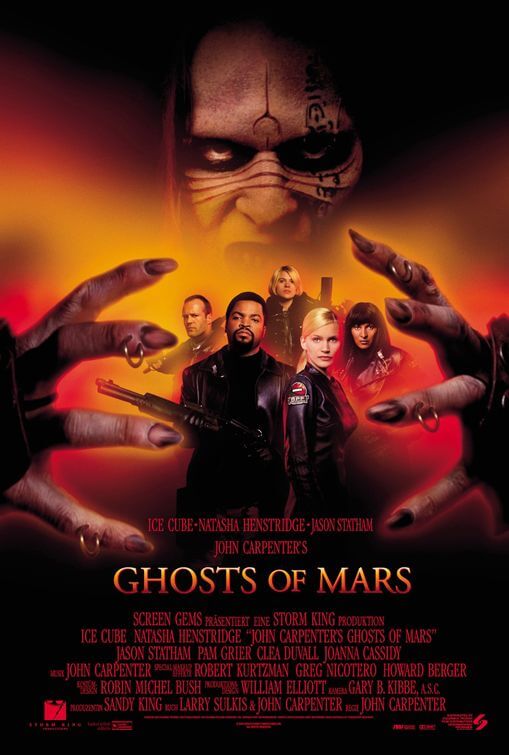

Ghosts of Mars

By Brian Eggert |

Even among ‘Master of Horror’ John Carpenter’s most devoted followers, Ghosts of Mars has a sour reputation. The director’s fans customarily rank his 2001 effort alongside Vampires and Village of the Damned as one of his very worst. And yet, the movie combines attributes spanning Carpenter’s entire career to deliver a satisfying concoction on a level of auteurist investigation, as well as basic genre entertainment value. Part Western, part sci-fi actioner, part grisly horror, the release has no pretenses about its own B-movie status. Aside from two or three titles with political implications, the movie’s goals are no loftier than the majority of Carpenter’s works, which is to say it merely wants to amuse those of us interested in the kind of movie where Ice Cube fights punked-out zombie aliens on Mars.

For a period in the early 2000s, before NASA announced the ending of the space program and Mars was the next viable goal for space exploration, Hollywood related America’s fascination with Mars through a trio of science-fiction movies about our sister planet—not unlike the duo of killer meteorite movies in the ‘90s (Armageddon and Deep Impact). First came Brian De Palma’s grossly underwhelming Mission to Mars (2000), a film with heady ideas but schmaltzy writing that turned an interesting concept into an uneven and literalized nod to Kurbick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. Next was Red Planet (2000), a thriller where a crew of explorers on Mars’ surface contends with flesh-eating bacteria and an endless string of equipment trouble, including a killer dog-like robot. After these two titles, audiences were more than finished with the Mars setting and unwilling to approach Ghosts of Mars, debuting a year later, with an open mind.

Box-office receipts were lousy, and, overall, critics panned the movie. Rotten Tomatoes holds a 20% “Rotten” rating. Writing for Entertainment Weekly, Bruce Fretts called the movie “borderline incoherent” and suggested Carpenter’s efforts were driven by “incompetence.” Robert Koehler’s review in Variety condemns the movie and claims it could only appeal to drive-in crowds, “a bygone filmgoing culture that reveled in cheap chills and thrills.” Despite Koehler’s understanding of the movie’s exploitative intentions, he points out such characteristics with disdain, as though Carpenter had a haughty objective but failed miserably. Not so. Among the few detractors who grasped the raw moviegoing simplicity behind Carpenter’s purpose was Roger Ebert, who said of the movie, “[It’s] all basic stuff, and yet Carpenter brings pacing and style to it.” But then, Ebert has always had a soft spot for B-movies.

Shot with a $28 million budget, relatively high for a Carpenter picture, Ghosts of Mars was filmed almost entirely at night at a New Mexico gypsum mine. White gypsum was dyed with thousands of gallons of biodegradable red dye to create the Martian landscape, and the effect is far more tangible and believable than other CGI-enhanced Martian backdrops. Star Natasha Henstridge (from Species) signed on last minute after the original cast member, Courtney Love (!), bowed out due to a domestic injury. And though Jason Statham was cast in a major role after standing out in Guy Ritchie’s Lock, Stock, and Two Smoking Barrels and Snatch, he was demoted with the hiring of Ice Cube, who was then a larger box-office draw. Today the opposite would be true. When the strenuous shoot had been completed, Carpenter found himself suffering from filmmaking exhaustion and temporarily retired from Hollywood, and survived off the royalties from several Halloween spin-offs and a remake of The Fog, until 2011, when he released The Ward.

Shot with a $28 million budget, relatively high for a Carpenter picture, Ghosts of Mars was filmed almost entirely at night at a New Mexico gypsum mine. White gypsum was dyed with thousands of gallons of biodegradable red dye to create the Martian landscape, and the effect is far more tangible and believable than other CGI-enhanced Martian backdrops. Star Natasha Henstridge (from Species) signed on last minute after the original cast member, Courtney Love (!), bowed out due to a domestic injury. And though Jason Statham was cast in a major role after standing out in Guy Ritchie’s Lock, Stock, and Two Smoking Barrels and Snatch, he was demoted with the hiring of Ice Cube, who was then a larger box-office draw. Today the opposite would be true. When the strenuous shoot had been completed, Carpenter found himself suffering from filmmaking exhaustion and temporarily retired from Hollywood, and survived off the royalties from several Halloween spin-offs and a remake of The Fog, until 2011, when he released The Ward.

Set in 2167, the movie opens with a train pulling into the Martian metropolis of Chryse City with only one passenger aboard, drug-addicted cop Melanie Ballard (Henstridge). Writers Carpenter and Larry Sulkis employ a non-linear structure through Ballard’s testimony to an official tribunal. As a result, the story is told through flashbacks, and flashbacks within flashbacks. And while normally this configuration would denote lousy storytelling, Carpenter uses it to establish a mystery built with frightening imagery and an eerie atmosphere, all leading to an explosive climax. Ballard and her crew—a group that includes Jericho (Statham), Helena (Pam Grier), and Bashira (Clea Duvall)—were tasked with a prisoner transfer of ruthless criminal Desolation Williams. As she tells her superiors, her squad arrives in the mining town of Shining Canyon to find it all but deserted, with signs that something horrible had occurred. The feeling of isolation, not only removed from humanity in the ghost town setting and, moreover, on a foreign planet, dominates the tone. Shadows move across the foreground accompanied by a jarring musical shrill, while Ballard’s squad finds odd-shaped decorations made from barbed wire and sharpened metal. Spatters of blood garnish the walls, and corpses are found hanging from the ceiling like in a slaughterhouse.

The prime suspect for their findings: Desolation Williams (Ice Cube), who is found quietly brooding in his cell. He claims he didn’t do it. And his story is confirmed when they find another survivor, a scientist named Whitlock (Joanna Cassidy), who tells them what they’re up against. She describes an archeological operation to uncover a Martian tomb. When Whitlock’s team opened the tomb, they released the souls of Martians who drift across the dusty plains in a gaseous red cloud, inhabit human host bodies, and turn them into bloodthirsty creatures led by “Big Daddy Mars” (Richard Cetrone) with a penchant for decapitations. When one of the hosts dies, the Martian’s spirit moves into another body, so there’s no stopping them. This relentlessly dire tone is offset by Desolations’ trio of criminal lackeys (Duane Davis, Lobo Sebastian, and Rodney A. Grant), who provide some comic relief during a scene involving some ill-advised chopping while under the influence.

As this collection of cops and crooks holes up inside a police station, hiding from the faceless horde outside and planning their next move, we cannot help but think of Carpenter’s first feature from 1976, Assault on Precinct 13, which in turn was a loose retelling of Howard Hawks’ archetypal Western Rio Bravo from 1959. Both sources feature cops defending their position against an oncoming horde of criminals. Perhaps Ballards’ use of psychedelic drugs is equivalent to Dean Martin’s alcoholism, and her crew tossing explosive sticks compares to John Wayne tossing dynamite and detonating it over the bad guys with a rile. Furthermore, the theme of cops and crooks banding together against a wholly indefinite force recalls Assault on Precinct 13, with Desolation Williams a badass alternate for Darwin Joston’s Napoleon Wilson—Carpenter’s first antihero of many. Ghosts of Mars feels like the next logical step in Carpenter’s homage to Hawks’ film, first with an update to a modern setting, and here infusing Westerns and science-fiction with railcar trains and ghost towns in a futuristic landscape.

Despite his harsh take on the movie, Koehler was wise enough to point out that, when asked once why he inserts his name before the title of his films, Carpenter responded, “Who else would make these movies?” Indeed, Carpenter’s affinity for low-key, low-budget horror and genre exploration has defined his reputation. Those of us intrigued by his Westworld-esque blend of Westerns and science-fiction are true genre enthusiasts. And, just like the blending of genres, those of us who see Ice Cube in camouflage pants and a black sleeveless tank and think of Kurt Russell’s Snake Plissken from Carpenter’s Escape from New York, and deem the costuming inspired instead of derivative, are true Carpenter devotees. The director’s persistent themes pour out of Ghosts of Mars, not merely because of Ice Cube’s effective antihero performance. Themes from The Thing and They Live—where an invisible enemy overtakes a small group of protagonists one by one in a claustrophobic setting, only to finally surface with graphic violence—also drive this movie. Some critics have pointed out that Carpenter retreads his previous work out of laziness, but if he didn’t explore these themes again and again, then he would hardly deserve his auteur status.

Despite his harsh take on the movie, Koehler was wise enough to point out that, when asked once why he inserts his name before the title of his films, Carpenter responded, “Who else would make these movies?” Indeed, Carpenter’s affinity for low-key, low-budget horror and genre exploration has defined his reputation. Those of us intrigued by his Westworld-esque blend of Westerns and science-fiction are true genre enthusiasts. And, just like the blending of genres, those of us who see Ice Cube in camouflage pants and a black sleeveless tank and think of Kurt Russell’s Snake Plissken from Carpenter’s Escape from New York, and deem the costuming inspired instead of derivative, are true Carpenter devotees. The director’s persistent themes pour out of Ghosts of Mars, not merely because of Ice Cube’s effective antihero performance. Themes from The Thing and They Live—where an invisible enemy overtakes a small group of protagonists one by one in a claustrophobic setting, only to finally surface with graphic violence—also drive this movie. Some critics have pointed out that Carpenter retreads his previous work out of laziness, but if he didn’t explore these themes again and again, then he would hardly deserve his auteur status.

Each production element looks at once backward and forward, borrowing from established tropes and innovating upon them with the personal touch that classifies Carpenter’s craft. Production designer William Elliott instills Shining Canyon with leathery details of a dilapidated Western town, yet the entire set piece looks self-contained, as though shot entirely in a sound stage, affording incredible detail within this confined space. The Martian hordes (designed by makeup crew Robert Kurtzman, Greg Nicotero and Howard Berger) look like gory rejects from a Marilyn Manson backup singer audition—horribly campy, yet undeniably creepy and effective as their trancelike behavior sends them into bouts of self-mutilation and piercing. And the score, composed by Carpenter, with help from bands Buckethead and Anthrax, suggests the heavy metal aspirations of the production. Through it all, Carpenter maintains his frame’s composure thanks to his cinematographer Gary B. Kibbe, whose steady, no-frills lensing delivered Prince of Darkness and In the Mouth of Madness.

With Ghosts of Mars, Carpenter recognizes and explores a general appeal behind the convergence of the Western and science fiction, his instincts dead-on, as audiences experienced similar experiments of late with Hollywood’s big-budget releases of Priest and Cowboys & Aliens. With about one-fifth the budget, however, Carpenter’s amalgamation of genres is far more successful, allowing each opposing genre to flourish, rather than one overcoming the other. When combined, components that shouldn’t work together do, making the result a funhouse of familiar ideas and retro stylization assembled in the tradition of B-movies. Granted, Ghosts of Mars doesn’t pretend to require heavy thought or provoke reactions beyond the basest of rudimentary moviegoing (as the head-banging score indicates). And even the most stringent Carpenter apologist cannot claim the movie feels as inspired as The Thing or Escape from New York. But it’s hardly “incompetent” either. Simply stated, for moviegoers who enjoy an abundance of badassery and the occasional decapitation, this is a fun and underrated movie deserving of any Carpenter fan’s affection.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review