Ghost in the Shell

By Brian Eggert |

Drawing from and building upon science-fiction’s ubiquitous questions about the nature of Self in the face of burgeoning technology, Masamune Shirow’s 1989 manga Ghost in the Shell explored the relationship between humanity, robotics, and an early form of the internet. Mamoru Oshii’s popular 1995 anime adaptation turned the story into a cult classic that shaped The Matrix, among many other films. After nearly thirty years of gestating to form a now-cemented nostalgia, the story has become an essential intellectual property. And since Hollywood’s obsession with thirtysomething franchises, nostalgia, and live-action versions of popular animated fare has achieved a peak, it seems inevitable that a Scarlett Johansson-starring Ghost in the Shell would arrive in theaters. But unlike the source material or animated film, the live-action production, released by Paramount Pictures, exists less as an essential addition to its genre than a chance to exploit its name brand.

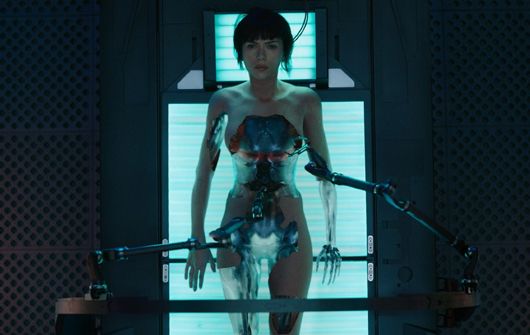

Director Rupert Sanders delivers another gorgeous looking picture; following his lavish but empty 2012 debut on Snow White and the Huntsman, he establishes himself as a visualist filmmaker. The story takes place in an uncertain future in New Port City, a megalopolis amalgamated from Hong Kong, Toyko, and several cities from sci-fi essentials (Metropolis, Blade Runner, etc.). Sanders and his team of FX wizards indulge in sweeping shots of the city, where digitized holographic advertisements intrude on the skyline. As characters walk or drive down any street, the filmmakers inundate each frame with flashing, floating animated ads, a design for the future explored in Minority Report and satirized in The Zero Theorem. It’s a rather stunning view and the viewer could easily find themselves lost in the details of any given shot. Additionally, the many cybernetically enhanced humans throughout the film appear to be CG-rendered, at least their mechanical parts, giving the viewer an endless source of visual stimuli. But, as is often the case with visualists, the quality of the storytelling in Sanders’ film does not live up to the eye candy.

Actually, most of the screenplay by Jamie Moss, William Wheeler, and Ehren Kruger improves upon Oshii’s anime. Fans of the original film cling to its existentialism and influence, but it was an emotionless experience—a downfall the writers of the new film have corrected. Bonds between characters have been filled in, the story’s personal significance has been linked to character backstories, and emotional connections firmly established. There’s even some warmth among these otherwise cold, cynical perspectives of the future. And while mild controversy looms over Johansson playing a character originally determined to be Japanese, the English- and Japanese-language production features performers from Denmark, Singapore, France, Australia, England, Romania, and Japan as well. Indeed, Ghost in the Shell was made in the spirit of multiculturalism with a bankable international star at the forefront.

Actually, most of the screenplay by Jamie Moss, William Wheeler, and Ehren Kruger improves upon Oshii’s anime. Fans of the original film cling to its existentialism and influence, but it was an emotionless experience—a downfall the writers of the new film have corrected. Bonds between characters have been filled in, the story’s personal significance has been linked to character backstories, and emotional connections firmly established. There’s even some warmth among these otherwise cold, cynical perspectives of the future. And while mild controversy looms over Johansson playing a character originally determined to be Japanese, the English- and Japanese-language production features performers from Denmark, Singapore, France, Australia, England, Romania, and Japan as well. Indeed, Ghost in the Shell was made in the spirit of multiculturalism with a bankable international star at the forefront.

Johansson plays Major Mira Killian, a soldier for the elite Section 9 task force. After an accident in which her family died and she was unrecoverably injured, her brain became the first human mind attached to a completely cybernetic body. Now an elite weapon designed by the motherly Dr. Ouelet (Juliette Binoche) but considered property by Hanka Corporation CEO Cutter (Peter Ferdinando), the Major begins to question her identity after a hacker named Kuze (Michael Pitt) begins targeting Hanka executives. Alongside her tough-but-tender partner Batou (Pilou Asbaek), and under the instruction of her noble Section 9 head (legendary Japanese action director-star “Beat” Takeshi Kitano), the Major comes to realize that everything she’s been told about her inception isn’t true, and perhaps Kuze has the answers she needs for self-discovery.

While many icy qualities of Oshii’s anime have been warmed up, the film’s devotion to the original’s basic plot combines with its unfortunate Hollywoodisms to sour the overall experience. Without getting into specifics, the ending has one of those typical blockbuster conclusions—the sort that feels compelled to summarize the film through clunky narration, despite the fact that no narration whatsoever was used earlier. It’s the sort of unwieldy narration that repeats several themes, as if to present a reminder of the film’s own thematic significance (“It’s not what I am. It’s what I do that matters.”). Along with some obvious cutting choices by editors Billy Rich and Neil Smith to avoid showing violence and nudity, thus ensuring a box-office friendly PG-13 rating, the film seems to have been compromised, but not unrecoverable. If a “director’s cut” or “unrated edition” on home video correct these issues (as they often tend to do), then this would be a much more positive review. Even so, a tamed version of Ghost in the Shell seems curious, given how similar material like The Matrix was R-rated and performed well, while lately a restricted rating seems to be a badge of honor for titles like Deadpool and Logan.

Aesthetically, Ghost in the Shell looks and sounds incredible. Production designer Jan Roelfs (Gattaca) captures the anime’s appearance, where futuristic technology has tried to cover up the otherwise crumbling cityscape, while certain scenes, particularly the famous invisible water fight and the spider-tank finale, look like shot-for-shot recreations. Of course, watching a live-action replica of the 1995 anime leaves the viewer in comparison mode as opposed to feeling engaged. Hollywood has yet to learn the true meaning of the word “adaptation” when it comes to certain intellectual properties. And so, ironically enough, people unfamiliar with the original may be the best audience for Sanders’ film. Elsewhere, composers Clint Mansell and Lorne Balfe engage in a mostly synth score that rivals Daft Punk’s work on TRON: Legacy. But the best flourish of all belongs to the performers. Johansson, Asbaek, Binoche, and Kitano bring life to their characters and give them deeper personalities than the anime allowed.

Aesthetically, Ghost in the Shell looks and sounds incredible. Production designer Jan Roelfs (Gattaca) captures the anime’s appearance, where futuristic technology has tried to cover up the otherwise crumbling cityscape, while certain scenes, particularly the famous invisible water fight and the spider-tank finale, look like shot-for-shot recreations. Of course, watching a live-action replica of the 1995 anime leaves the viewer in comparison mode as opposed to feeling engaged. Hollywood has yet to learn the true meaning of the word “adaptation” when it comes to certain intellectual properties. And so, ironically enough, people unfamiliar with the original may be the best audience for Sanders’ film. Elsewhere, composers Clint Mansell and Lorne Balfe engage in a mostly synth score that rivals Daft Punk’s work on TRON: Legacy. But the best flourish of all belongs to the performers. Johansson, Asbaek, Binoche, and Kitano bring life to their characters and give them deeper personalities than the anime allowed.

Ghost in the Shell is best when it concentrates on exploring Major’s search for identity, such as understated scenes in which Johansson connects with a stray dog, a female prostitute, or her mother in exploratory moments of her own humanity. As evidenced in Under the Skin, Johansson is capable of emoting layers of ponderous feeling that go beyond limitations of the source material or the remake’s screenplay. But the filmmakers resolve to concentrate their attention more on action set-pieces—and there are several impressive ones—a choice that ultimately results in a film not unlike its protagonist: caught between two states, human and robot, or in the film’s case action movie and existential sci-fi. Ghost in the Shell has too much potential emotion to be another version of The Matrix; and while it approaches the mysterious humanism of Blade Runner, the presentation has been shaped to Hollywood specifications and robbed of its potential uniqueness, insight, or innovation.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review