Ghost in the Shell

By Brian Eggert |

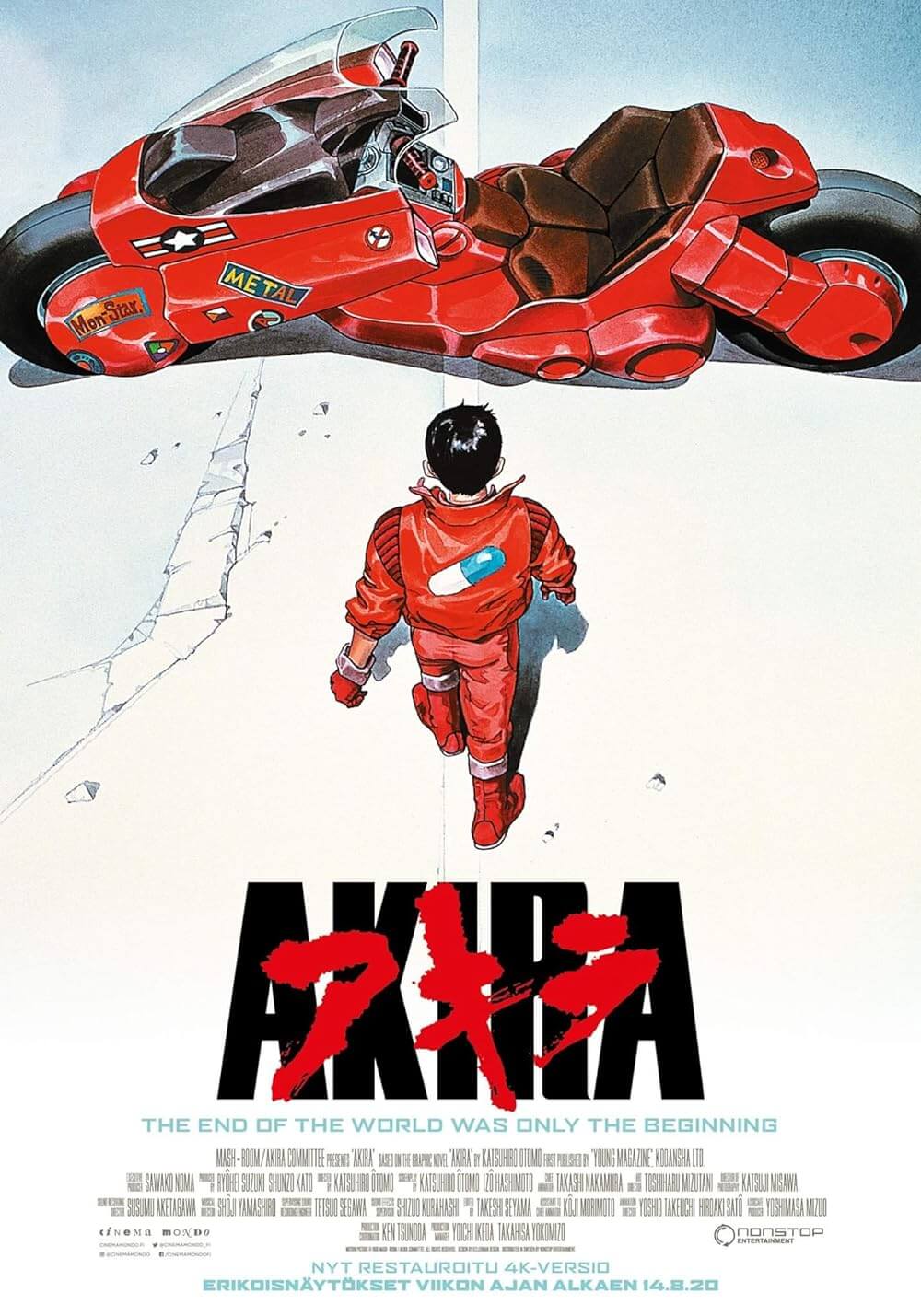

Cyberpunk and Japanese animation aficionados drool over Ghost in the Shell, the influential 1995 feature that, along with Akira in 1988 and the entire oeuvre of Hayao Miyazaki, marked the popularization of anime overseas. After anime’s proved popular outside of its country of origin, animators began catering to the other markets, and many fans feel that the purity of the Japanese artistry lessened—which is to say, became westernized—as a result. Ghost in the Shell was a major contributor to anime’s increasing popularity; its posters could be found on college dorm room walls alongside those for The Boondock Saints and Scarface. But like many other anime titles of its day, the film has not aged well, emphasizing the cultish, fad-level enthusiasm for anime in the 1990s. Nevertheless, its contribution to science-fiction remains more significant even than its status as an anime.

Based on the serialized 1989 manga by Masamune Shirow, Ghost in the Shell was directed by Mamoru Oshii, and it remains his most successful and popular film (next to his Patlabor series and the 2004 sequel, Ghost in the Shell: Innocence). Kazunori Ito, Oshii’s frequent collaborator, wrote the screenplay, though the director’s vision shaped the film. Oshii’s preoccupation with futureworlds and the infancy of the digital age led to an exploration of these themes. Looking back, Oshii reflected a very specific paradigm in which the understanding of computers and the internet was limited. Take the now-laughable title sequence that displays archaic, Windows 95-level computer animations that were rather rudimentary even in 1995. Such animations are more memorable for their use of neon green letters on a black digital plane (following the look of every computerized corporate interface from the preceding decade).

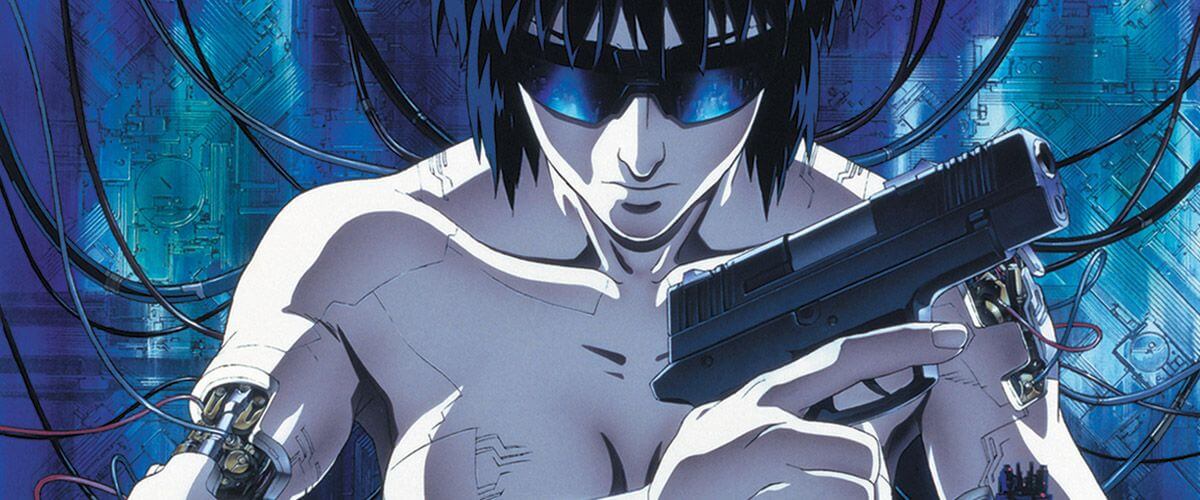

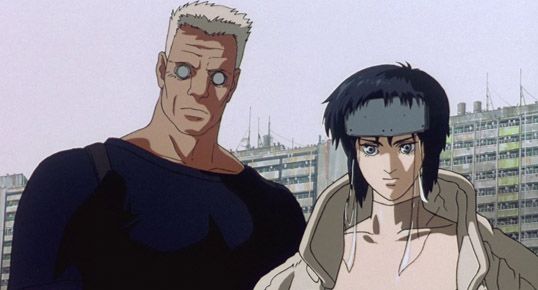

Set in 2029, the story takes place in the vast New Port City, which appears to be in the beginning stages of gentrification. Technology has been ungainly applied to buildings and human beings alike. It’s a world of cyborgs, as most people have robotic body parts, while others exist as a human consciousness inside of a “shell”—a robot body with special abilities (super strength, invisibility, etc.). The story follows public security officer Major Motoko Kusanagi, whose voluptuous body is a factory model and mostly always nude (shame and modesty do not apply when your body is not real). She and her partners, the sharpshooter Batou and regular guy Ishikawa, are tasked with capturing an American hacker-terrorist known as the Puppet Master. But as Maj. Kusanagi eventually learns, the Puppet Master achieved consciousness after being created by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs as a covert hacking weapon. After Maj. Kusanagi and the Puppet Master are both nearly destroyed in a climactic battle, they merge together as one, forming a new being comprised of multiple layers of technology and consciousness.

Set in 2029, the story takes place in the vast New Port City, which appears to be in the beginning stages of gentrification. Technology has been ungainly applied to buildings and human beings alike. It’s a world of cyborgs, as most people have robotic body parts, while others exist as a human consciousness inside of a “shell”—a robot body with special abilities (super strength, invisibility, etc.). The story follows public security officer Major Motoko Kusanagi, whose voluptuous body is a factory model and mostly always nude (shame and modesty do not apply when your body is not real). She and her partners, the sharpshooter Batou and regular guy Ishikawa, are tasked with capturing an American hacker-terrorist known as the Puppet Master. But as Maj. Kusanagi eventually learns, the Puppet Master achieved consciousness after being created by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs as a covert hacking weapon. After Maj. Kusanagi and the Puppet Master are both nearly destroyed in a climactic battle, they merge together as one, forming a new being comprised of multiple layers of technology and consciousness.

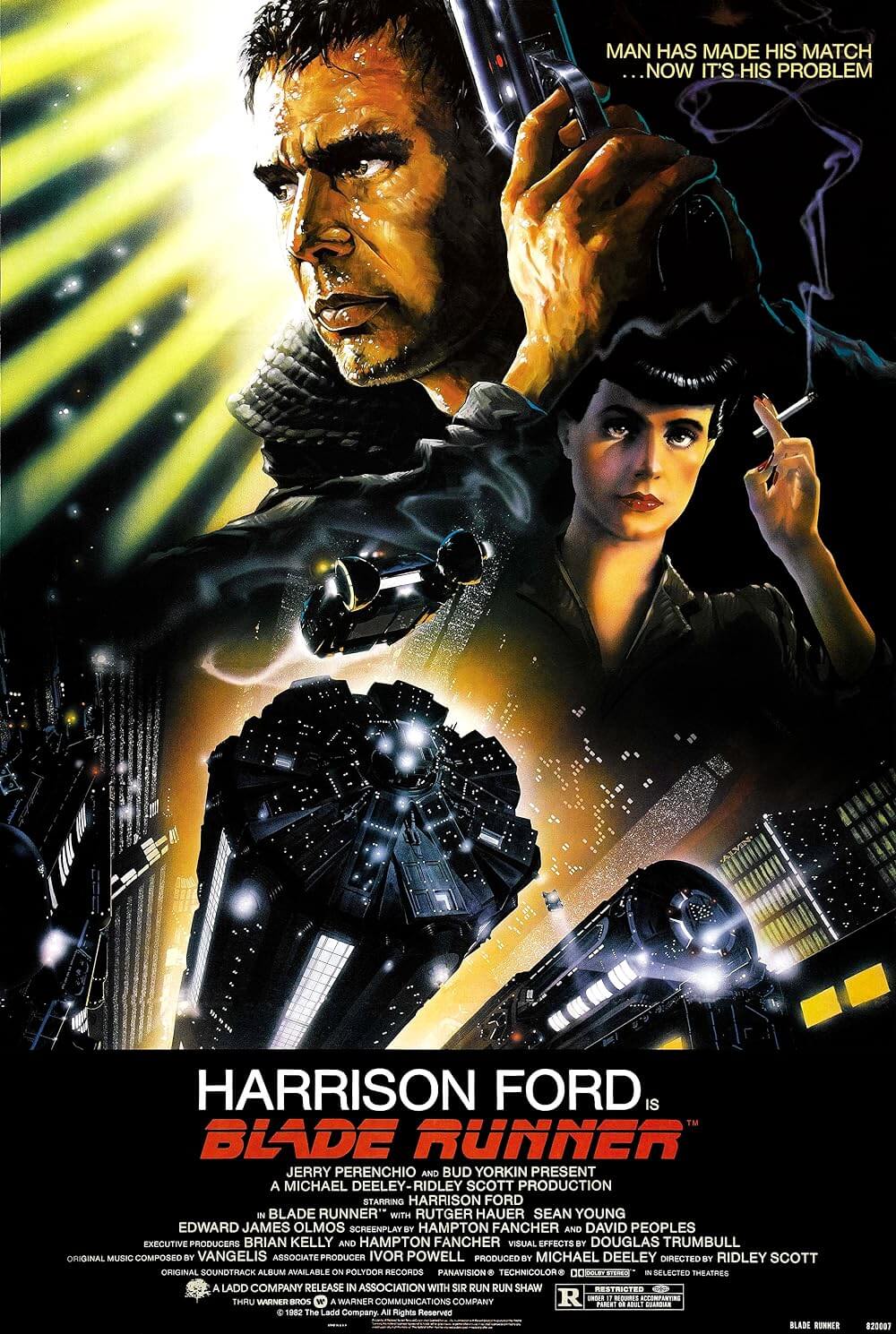

Ghost in the Shell is also a neo-noir mystery in the same way as Blade Runner, and both films contain a hero who achieves a sort of transcendent revelation in the finale. But Oshii’s film is perhaps overly concerned with its ideas about technology. Rather than developing characters through action and personality, the script’s wooden dialogue pours out in expositional form, rendering the technological themes inescapable. Maj. Kusanagi ruminates, “There are countless ingredients that make up the human body and mind, like all the components that make up me as an individual with my own personality. Sure, I have a face and voice to distinguish myself from others, but my thoughts and memories are unique only to me, and I carry a sense of my own destiny.” The film ponders whether humanity is reserved for human beings or even just a scanned ghost within a shell. Or can the synthesis of an artificial mind and body create its own soul?

Such questions linger in the external script, as opposed to the subtext where they belong, and don’t delve into characterization beyond the dense plot. Running 82 minutes, much of the film exists as a setup for grandiose revelations that have minor emotional resonance. They are mind-blowing for their story machinations and the questions they incite after viewing, but the discussion within the film itself is rudimentary. Consider the vague implications of Ghost in the Shell’s final line, “Time to become a part of all things.” The reference remains ambiguous in part because Oshii has not thoroughly explored the implications of his science-fiction world. Hints that people can “ghost hack” another mind and draw from its knowledge or memories are alluded to, but not adequately discussed, nor is the apparent network of connectivity that would allow the Maj. Kusanagi-Puppet Master hybrid to indeed become part of all things.

For every cumbersome hunk of dialogue or underexplored idea, there’s a gorgeously animated action set piece or beautiful, soft-filtered visual sequence. Much of the imagery and many of its themes have been borrowed from other material or replicated elsewhere. Its cityscape, which Oshii based on Hong Kong, contains buildings that reach as high as those in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis; though, they also recall those of Blade Runner, decrepit and falling apart, and what’s more drenched in an omnipresent rain. A beautiful montage sequence looks around the city to a hypnotic choral score, a wedding song no less, while a procession of boats on the flooded canal streets evokes melancholy. The sequence shows us a world that combines old and new spliced together into an ungainly whole, not unlike the protagonist. Meanwhile, the interface cords that input into the back of a shell’s neck were borrowed for The Matrix, and the Wachowskis also evoked Ghost in the Shell’s title sequence and computer animations in their now-iconic representation of the Matrix’s numbered rainfall.

For every cumbersome hunk of dialogue or underexplored idea, there’s a gorgeously animated action set piece or beautiful, soft-filtered visual sequence. Much of the imagery and many of its themes have been borrowed from other material or replicated elsewhere. Its cityscape, which Oshii based on Hong Kong, contains buildings that reach as high as those in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis; though, they also recall those of Blade Runner, decrepit and falling apart, and what’s more drenched in an omnipresent rain. A beautiful montage sequence looks around the city to a hypnotic choral score, a wedding song no less, while a procession of boats on the flooded canal streets evokes melancholy. The sequence shows us a world that combines old and new spliced together into an ungainly whole, not unlike the protagonist. Meanwhile, the interface cords that input into the back of a shell’s neck were borrowed for The Matrix, and the Wachowskis also evoked Ghost in the Shell’s title sequence and computer animations in their now-iconic representation of the Matrix’s numbered rainfall.

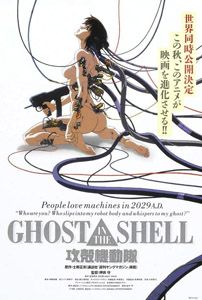

Thematically, Maj. Kusanagi has been the center of a conversation about Ghost in the Shell’s portrayal of female strength and independence. Anime often depicts women as headstrong heroes, impressive fighters, and protectors of a noble morality—all while objectifying the female form with a fetishized representation of their bodies (Roger Ebert addressed this trend in the film in his review as well). It’s an unfortunate ideological conflict that’s evident throughout Ghost in the Shell, and even its poster. Similarly, Maj. Kusanagi could be seen as the future of female reproduction in a cyborg world. Though she has no sexual reproductive organs (she’s like Barbie down there), she merges with the Puppet Master to form a third, unique psyche in an ostensible procreation without coitus. Through this process, the parental units must sacrifice themselves for a child that contains all the data of its parents, yet also harbors a new consciousness. Unfortunately, any apparent theme of sexuality or reproduction remains projected by the viewer, since the screenplay avoids addressing gender in the cyborg world outside of the events of the thin plot.

To be sure, Ghost in the Shell is part of a long tradition of science-fiction films that consider the limits of humanity, technology, and the potential for consciousness within an artificial intelligence—all existing in a dystopian future. Though its female hero stands as a genre icon of strength and badassery, Maj. Kusanagi and her prominent nipples have nonetheless been animated to turn on the same audience she’s meant to inspire. With another half-hour and a script with more subtlety (and fewer exploitative artistic renderings of the female form), the film may have explored its themes with a greater sense of grace and emotion. Alas, Ghost in the Shell relies on a surface-level investigation of its ideas and images. Of course, fans of the cyberpunk and sci-fi genres must be thankful for its existence and unmistakable vision, while others should revisit the film to witness how it incited other directors to make better films.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review