Get Out

By Brian Eggert |

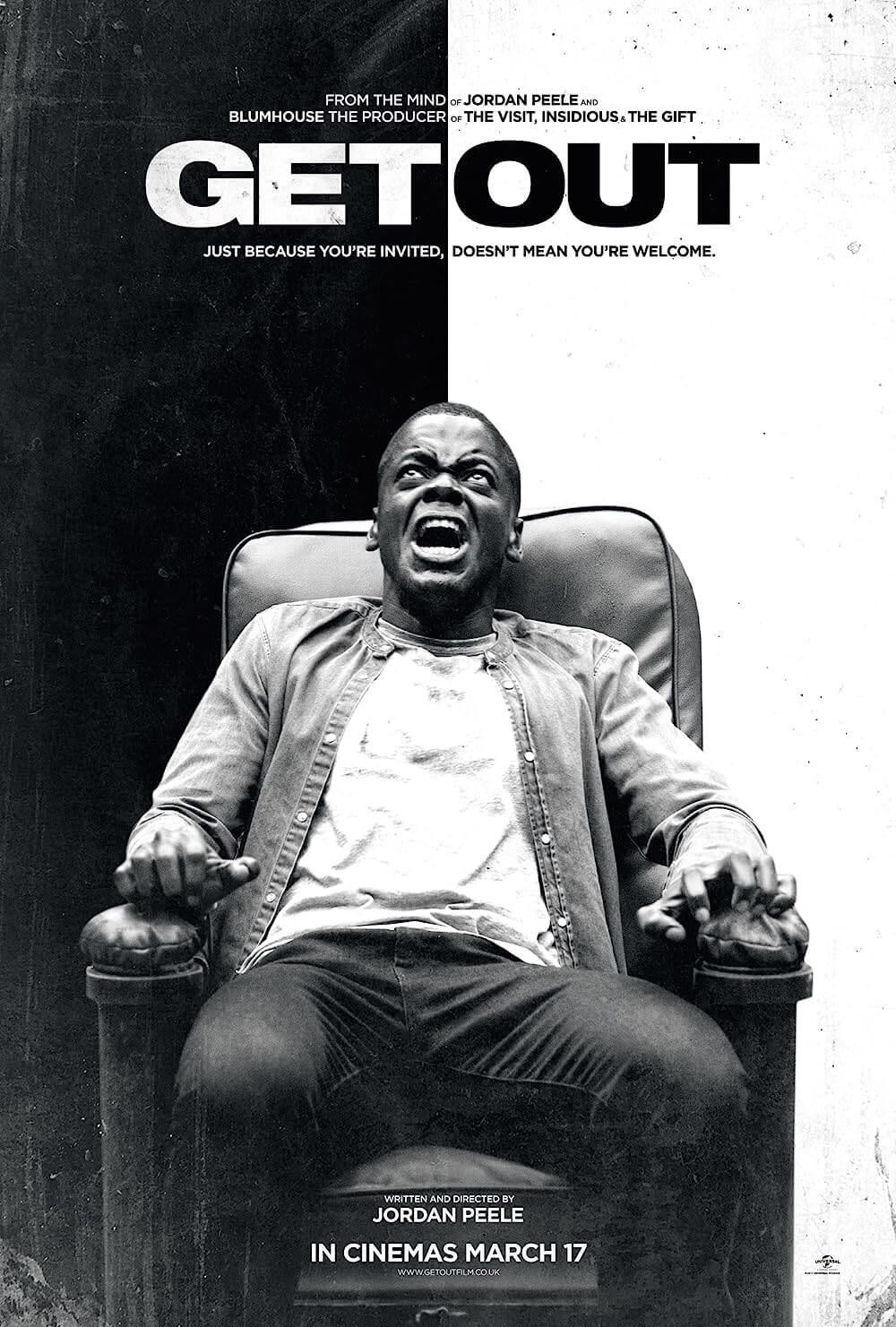

Get Out marks the filmmaking debut of Jordan Peele, who offers a rare, exceptional addition to the Blumhouse Productions label. Jason Blum’s factory of schlocky supernatural horror—steeped in franchises like Insidious, Paranormal Activity, and The Purge—receives a much-needed injection of vitality and vision here. Serving as both writer and director, Peele puts his apparent love of genre films into something far more searing than a common homage; instead, he engages an unnerving shocker that doubles as a burning sociopolitical satire about the racist state of America. From the first scene that evokes the fate of Trayvon Martin, to the sinking feeling of the final sequence when a cop car arrives at an uncertain moment, Get Out seems inspired by headlines yet not dependent on them. But like the best genre films, Peele’s debut does not sacrifice its story or entertainment value to stand on a soapbox and proclaim its commentary.

Alongside Keegan-Michael Key, Peele followed his five-year run on the lauded sketch-comedy show Key & Peele with 2016’s serviceable laugher Keanu. Comedy aside, fans will remember Key and Peele’s passion for horror flicks from Halloween episodes, while movie spoofs in general were a regular function of their show. Suffice it to say, Peele is a movie geek. To underscore this, the first-time filmmaker saturates Get Out with influence from Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, The Stepford Wives, and The Manchurian Candidate. An argument could also be made for The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, since both films involve unwitting victims walking into a veritable house of horrors. Indeed, Peele has since announced (to Variety) his intention to remain behind the camera, exploring the “human demon” with a series of social thrillers. The demon of Get Out is racism, and Peele has remarked that his experiences growing up biracial in America were a nightmare.

In the eerie prologue, a Black man (Keith Stanfield) follows some bad directions into a wealthy white community whose quiet, empty streets emanate a sense of dread. The sequence flips the cliché of white people driving through a “bad urban neighborhood” on its head when a car pulls up alongside him and, as you might guess, it doesn’t end well. This opener echoes Peele’s theme of Get Out: being black in America is a living horror show. The film settles on young photographer Chris (Daniel Kaluuya, from the Black Mirror episode “Fifteen Million Merits”), who prepares for a weekend trip to meet his girlfriend’s family. Rose (Allison Williams, from Girls) maintains that her affluent parents aren’t racist, though she concedes her father will probably mention to Chris how he would vote for Obama a third time if he could. So just casually racist.

When they arrive at the elaborate, secluded estate of Rose’s parents, Chris finds himself in the company of white liberals who seem desperate to bond with their new Black guest. Rose’s father Dean (Bradley Whitford) uses phrases like “my man” and “thang,” while her mother Missy (Catherine Keener), a hypnotherapist, seems oddly preoccupied with helping Chris kick his smoking habit. Less well-meaning is Rose’s unstable brother (Caleb Landry Jones) and his allusions to Chris’ “genetic” physical superiority. Chris reacts to this nonchalantly racist behavior with subtle, often silent reactions. Kaluuya does a lot with his eyes and slight expressions that suggest Chris has been in similar circumstances before, even as he preserves some disbelief over the awkward situation. It’s an understated, rather brilliant performance.

But Chris’ restraint gives way as the oddities build up. Initially, he questions minor details. Why do Rose’s parents employ a Black groundskeeper (Marcus Henderson) and maid (Betty Gabriel), and worse, behave toward them with an air of superiority? Why does someone keep unplugging his smartphone from the charger? At the family party the next day, why do the guests treat Chris like a specimen (one woman grabs his arm as if inspecting livestock)? Only a single guest (Stephen Root), who happens to be blind, seems concerned with Chris’ photography skills over his racial identity. When Chris tries to address such peculiarities with Rose, she dismisses them as paranoia. Soon enough, the minor details add up into an altogether more terrifying and sinister development. And these questions haven’t even addressed the fantastical elements of the film.

But Chris’ restraint gives way as the oddities build up. Initially, he questions minor details. Why do Rose’s parents employ a Black groundskeeper (Marcus Henderson) and maid (Betty Gabriel), and worse, behave toward them with an air of superiority? Why does someone keep unplugging his smartphone from the charger? At the family party the next day, why do the guests treat Chris like a specimen (one woman grabs his arm as if inspecting livestock)? Only a single guest (Stephen Root), who happens to be blind, seems concerned with Chris’ photography skills over his racial identity. When Chris tries to address such peculiarities with Rose, she dismisses them as paranoia. Soon enough, the minor details add up into an altogether more terrifying and sinister development. And these questions haven’t even addressed the fantastical elements of the film.

Peele has loaded Get Out with secrets and twists galore, beyond what any audience could ever hope to guess. He reveals them in disturbing ways and, at every turn, he also comments on the social divisions between races, as well as economic divisions between the upper one-percent and, well, everyone else. In the last year, race has come to the forefront of most political discussions: Relations between police officers and African-American groups have intensified and grown tragically violent, a demonstrably racist commander-in-chief has been voted into the White House, Black Lives Matter continues to call for awareness, and talk of diversity seems painfully urgent everywhere you look. When Peele was writing his screenplay prior to 2015, he could not have known what was coming; and while recent headlines may bring the conversation into the media spotlight, it’s important to note: these are not new conversations, nor should the impassioned debate stop if ever the volatile political climate calms.

Though Peele’s film has plenty to say about people of color living in white-dominated society, he also follows several well-treaded tropes of the horror genre. Savvy viewers will see evidence of Rosemary’s Baby not only in the paranoid-nightmare-come-true scenario but also the humor Peele brings to the material. Chris’ best friend Rod (Lil Rel Howery) cuts the tension with humor; he launches his own investigation after learning about several disappearances of Black men in the area where Rose’s family lives. (He reports his findings to a detective, played by Living Single’s Erika Alexander, and her reaction is priceless.) Rod echoes that voice in the viewer’s head—the one shouting at Chris to “Get out!” before it’s too late—and his conspiracy theories about what’s going on prove funny, if surprisingly semi-accurate. Besides a comic relief sidekick, Peele relies on other clichés; however, each time he embraces a known formula he reinvigorates it.

On a formal level, Get Out shows Peele making smart choices about shadows and brooding camera movements alongside cinematographer Toby Oliver. He also incorporates chilling music, some of it piercing strings by Michael Abels, some of it just the right song for the scene (the old-timey tune “Run Rabbit Run” by Flanagan and Allen is appropriately unsettling). Most impressive is how well this freshman effort demonstrates Peele’s complete vision: his technique has an individual style, he exhibits his love of classic horror films without becoming overtly derivative, his personal touches and grim sense of humor are evident, and all while exploiting the evil beneath varying degrees of racism—from subtle to monstrous—in a thriller with germane overtones. Get Out is essential viewing for the socially conscious horror fan.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review