Reader's Choice

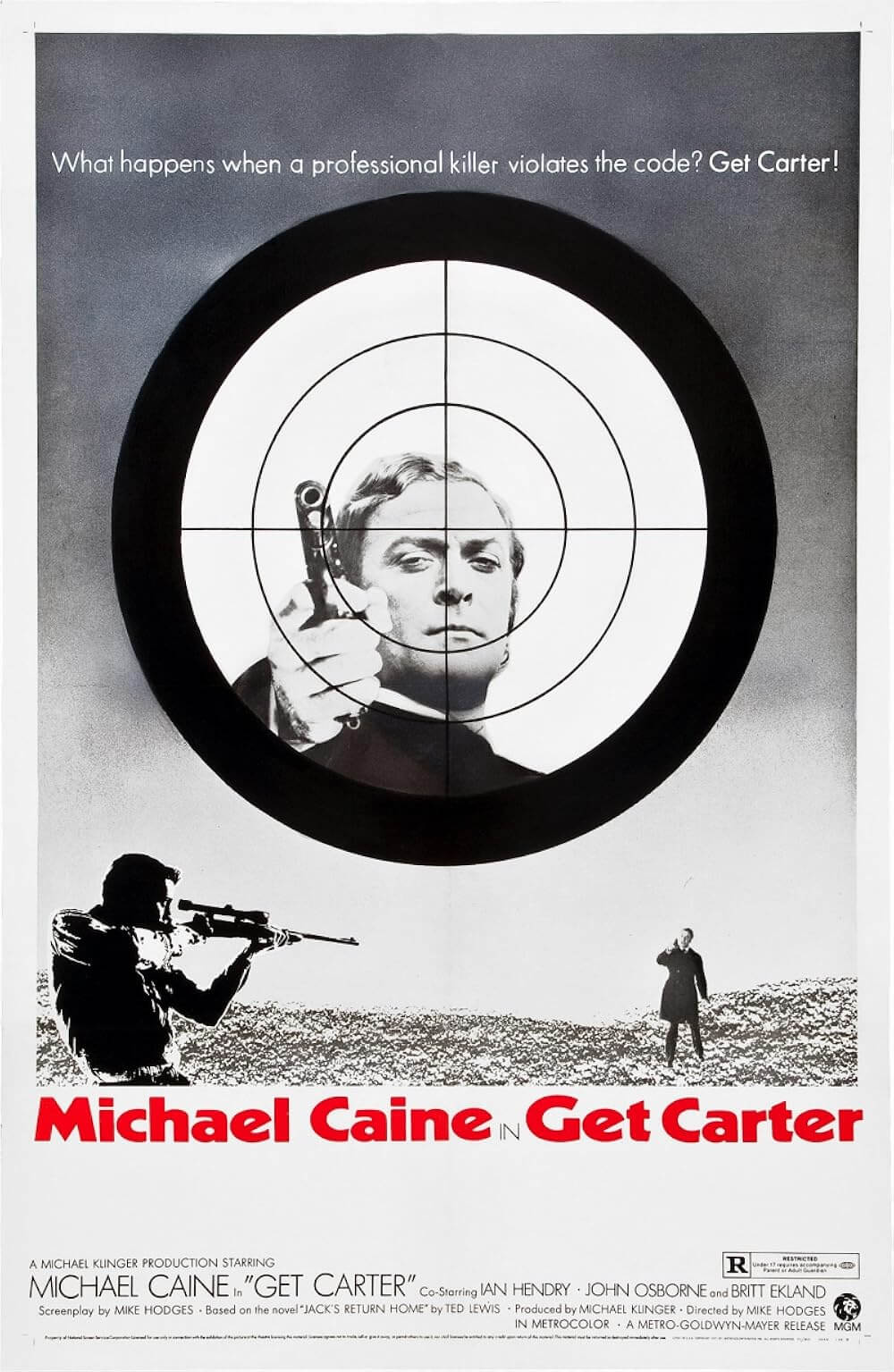

Get Carter

By Brian Eggert |

Get Carter is the volatile gangster film that solidified the British culture’s embrace of the genre. It came long before John Mackenzie’s The Long Good Friday (1980), Neil Jordan’s Mona Lisa (1986), or the advent of Danny Boyle, Guy Ritchie, and Matthew Vaughn—modern directors who repopularized the genre for a new generation and further integrated Lad Culture into the mainstream. The film is a harsh and unpleasant neo-noir more than a cucumber-cool portrait of the chic criminal underworld, complete with a protagonist doomed by his astounding number of character flaws. Michael Caine stars in an explosive performance as Jack Carter, the personification of unreconstructed masculinity. He’s a combination of his sexually zealous—but here unrepentant—chap from Alfie (1966) and a teeth-baring ruthlessness that only an actor of his caliber could render with such dimension, and do so again in Harry Brown (2009) decades later. Written and directed by Mike Hodges, Get Carter is a sordid tale of vengeance that for many, more even than Brighton Rock (1948) or any earlier landmarks, laid the foundation of the modern British gangster film.

The film opens when Carter, the creation of novelist Ted Lewis, departs northward from London to visit his “craphole” home of Newcastle, the corrupt steel town where his brother Frank has been murdered. Nevermind the fact that, along the title sequence’s train ride to Newcastle, Carter does about the most unmasculine thing imaginable: he eats a bowl of awful-looking creamy soup. During his quest for revenge, Carter throws a man off the roof of a building, stabs another, locks a porno actress in the trunk of a car that is later pushed into a river, murders a prostitute by giving her an overdose of heroin, and bludgeons a man to death. Carter also beds his landlady, has phone sex with his London boss’ girlfriend, and before locking that woman in his trunk, he has sex with her too. By all measures, Carter is a real bastard, and Get Carter is a nihilistic film shot with a sense of gritty realism instead of flashy displays of a glamorous gangster lifestyle. Caine’s mostly flat expressions throughout signal a routine quality to his nastiness, to the extent that he carries out his revenge at a temperature that rarely gets above ice cold. We’re left asking: Is he a badass or just plain bad?

The labyrinthine plot exposes a seedy system of racketeers, sex workers, and ruthless killers unto which Carter unleashes his retribution, and ultimately falls victim. Keeping track of who betrayed who and why may prove challenging. Here’s the gist of it: Off-screen, Carter’s brother Frank was murdered after seeing that his 16-year-old daughter (Petra Markham) was forced into an underground porno film arranged by a crime boss named Kinnear (John Osborne). A gambling machine operator, Brumby (Bryan Mosley), Kinnear’s competition, told Frank about the porno and encouraged Frank to take down Kinnear by alerting the police. In response, Kinnear’s henchman Eric Paice (Ian Hendry) murdered Frank by pouring alcohol down his throat and forcing him to drive, and the resulting accident appeared to be a case of drunk driving. On the screen, Carter learns about Eric’s role in his brother’s killing, and he arranges for a secluded meeting where he proceeds to force Eric to down an entire bottle of whiskey, just as Eric had done with Frank. But rather than shoot Eric, Carter beats the man to death, using a shotgun like a caveman’s club. Hodges’ significant departure from Lewis’ text is the final moment when a sniper, who has seemingly followed Carter the entire film, puts a bullet in our anti-hero’s brain, ending an already venomous film with a particularly cruel end.

The labyrinthine plot exposes a seedy system of racketeers, sex workers, and ruthless killers unto which Carter unleashes his retribution, and ultimately falls victim. Keeping track of who betrayed who and why may prove challenging. Here’s the gist of it: Off-screen, Carter’s brother Frank was murdered after seeing that his 16-year-old daughter (Petra Markham) was forced into an underground porno film arranged by a crime boss named Kinnear (John Osborne). A gambling machine operator, Brumby (Bryan Mosley), Kinnear’s competition, told Frank about the porno and encouraged Frank to take down Kinnear by alerting the police. In response, Kinnear’s henchman Eric Paice (Ian Hendry) murdered Frank by pouring alcohol down his throat and forcing him to drive, and the resulting accident appeared to be a case of drunk driving. On the screen, Carter learns about Eric’s role in his brother’s killing, and he arranges for a secluded meeting where he proceeds to force Eric to down an entire bottle of whiskey, just as Eric had done with Frank. But rather than shoot Eric, Carter beats the man to death, using a shotgun like a caveman’s club. Hodges’ significant departure from Lewis’ text is the final moment when a sniper, who has seemingly followed Carter the entire film, puts a bullet in our anti-hero’s brain, ending an already venomous film with a particularly cruel end.

Lewis drew inspiration for his book from the so-called one-armed bandit murder of 1967, a case that made headlines for signaling the presence of organized crime in the northeast of England, whereas before it was isolated in the southern region around London. The case involved the murder of Angus Sibbet, who had been skimming profits from the fruit machine business (slots) run by postwar gangster Vincent Luvaglio. Dennis Stafford and Vincent’s brother, Michael, were convicted of Sibbet’s murder. Before the 1960s, gangsterism had remained somewhat hidden from public view; along with Sibbet’s murder, a turf war between the infamous Kray twins and the Richardson gang dominated the underworld and earned widespread national attention. As such, representations of the British gangster in film have a unique identity, particularly in the mid-twentieth century. In the years between Brighton Rock, one of the earliest and most influential British gangster films, and Mona Lisa, one of the most revisionist and post-modern (especially in its recasting of Caine as a villain), the British gangster genre told personal stories that revealed an otherwise clandestine world to the audience. But they focused on the individual rather than the system, heightening their dramatic effect while, by extension, exposing the viewer to the harsh reality.

Unlike the glorified representations of American gangsterism in Hollywood films or the lyrical examples in the French works of Jean-Pierre Melville, the twentieth century’s British gangster reflects the significant effort that a British individual must go through to become a criminal, both psychologically and institutionally. It is more of a statement to be a British gangster in a film like Get Carter. Psychologically, the gangster stands in opposition to British identity. The typical—somewhat stereotypical—identity for a twentieth-century British person, men especially, include qualities such as restrained emotions, a prudent spending of money, sexual repression, and adherence to class decorum. This means that being a British gangster is to go against the typical British identity, representing a more significant psychological leap away from the status quo than, say, in American culture where crime and violence—qualities associated with gangsterism—are much more prevalent, even commonplace within the culture. The divide between British gangsters and the society in which they exist is far more expansive than those in other countries, and thus their stories naturally prove more rebellious and compelling.

Institutionally—politically, legally, or infrastructurally within the British state—it’s more challenging to access guns than in the United States. There’s a legal system in place that prevents a British person from owning a gun without the proper certifications. Carter’s gun, a double-barrel shotgun best used for upland hunting, is perhaps not an ideal weapon of an American gangster, but it’s how Carter can arm himself. Someone in the U.S. could get an assault rifle or handgun with few obstacles, whereas the act of equipping oneself as a British gangster requires that they either risk registering a firearm and getting caught using it in criminal activity, or they use stolen weapons. This represents another oppositional statement against the norm: the degree to which a British criminal has to go out of their way to acquire the tools of the gangster trade, at least compared to an American gangster, is significant, and so the act itself is more pronounced. The act has more symbolic meaning within the culture. Not only using a gun in criminal activity but having a gun is a statement and transgression. British gangsters are therefore not viewed as romantic opportunists as American gangsters often are; they’re seen as incompatible with the culture or, in many more recent cases, they’re romanticized for their rebellion against cultural strictures.

Institutionally—politically, legally, or infrastructurally within the British state—it’s more challenging to access guns than in the United States. There’s a legal system in place that prevents a British person from owning a gun without the proper certifications. Carter’s gun, a double-barrel shotgun best used for upland hunting, is perhaps not an ideal weapon of an American gangster, but it’s how Carter can arm himself. Someone in the U.S. could get an assault rifle or handgun with few obstacles, whereas the act of equipping oneself as a British gangster requires that they either risk registering a firearm and getting caught using it in criminal activity, or they use stolen weapons. This represents another oppositional statement against the norm: the degree to which a British criminal has to go out of their way to acquire the tools of the gangster trade, at least compared to an American gangster, is significant, and so the act itself is more pronounced. The act has more symbolic meaning within the culture. Not only using a gun in criminal activity but having a gun is a statement and transgression. British gangsters are therefore not viewed as romantic opportunists as American gangsters often are; they’re seen as incompatible with the culture or, in many more recent cases, they’re romanticized for their rebellion against cultural strictures.

Because gangsterism contradicts dominant values and institutions in British culture, there’s a need to suppress gangsters more than in other countries. As a result, for the majority of the twentieth century, British gangster films were considered B-movies of unworthy subject matter by many of the contemporary British censors, which is why few of them appeared in the first half of the century. Although they depicted the everyday lives of criminals that exist in British culture, these figures remained hidden from public view, unlike the public image of American gangsters in the headlines and Hollywood cinema. British gangsters were less high-profile in their crimes, whereas the Prohibition-Era gangsters in the U.S. were mythologized by the media and public into cult heroes. This isn’t the case with many real-life British gangsters, who were a dirty little secret, and so films about them were considered “underworld films” by many British scholars as opposed to “gangster films.” Certainly, the world depicted in Get Carter bears little resemblance to the age of the Tommy gun and the Italian mob in America; it’s located in an underbelly where seedy men carry out dirty deeds.

Part of this has to do with the nature of the crimes themselves. The British gangster’s crimes were taking place under the noses of the general public, and so putting them into a film is, in part, about exposing the viewer to this clandestine world of gangsterism. Watch Get Carter before the opening credits, where Carter and a few of his London cohorts sit around watching a graphic porno film—a shocking sight even by today’s standards. Although Carter seems uninterested, the viewer gets the full view of a degraded scene that shows group spectatorship of pornography, a far cry from a glamorous portrait of apparently commonplace underworld activity. To be sure, the picture of the British gangster is not defined by violence as American gangsters are, but rather their underworld-ness. The crimes of British gangsters aren’t so widespread as the creation and distribution of, say, illegal alcohol during Prohibition times, and the warring and body count that goes along with that. It’s in the vein of racketeering (money laundering, fraud, numbers, protection, extortion, loan sharking, dog fighting, and prostitution). These are not publicly visible crimes. They’re crimes in which an individual benefits from a system (hides money, pays for protection, gambles, etc.) that never impacts a large segment of the public as Prohibition did.

Hodges and cinematographer Wolfgang Suschitzky worked together to create an almost documentarian-style portrait of the British gangster’s underworld, using long lenses and actual locations to achieve a really-there effect. Besides shooting on city streets, Hodges picked places either once owned by or known to be associated with Vincent Luvaglio and those involved in the one-armed bandit murder. The effect gives Get Carter a sense of realism that purveyed the British gangster film for much of the twentieth century, a quality in aide of exposing the underground it represented. Around the early 1990s, after Quentin Tarantino repopularized the crime genre, Boyle’s Trainspotting (1996), Guy Ritchie’s Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels (1998) and Snatch (2000), and Jonathan Glazer’s Sexy Beast (2000) injected a flashiness and stylistic bravado that has remained associated with British gangster films to this day. But in the decades after Get Carter, the genre had been associated with a vérité aesthetic.

Hodges and cinematographer Wolfgang Suschitzky worked together to create an almost documentarian-style portrait of the British gangster’s underworld, using long lenses and actual locations to achieve a really-there effect. Besides shooting on city streets, Hodges picked places either once owned by or known to be associated with Vincent Luvaglio and those involved in the one-armed bandit murder. The effect gives Get Carter a sense of realism that purveyed the British gangster film for much of the twentieth century, a quality in aide of exposing the underground it represented. Around the early 1990s, after Quentin Tarantino repopularized the crime genre, Boyle’s Trainspotting (1996), Guy Ritchie’s Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels (1998) and Snatch (2000), and Jonathan Glazer’s Sexy Beast (2000) injected a flashiness and stylistic bravado that has remained associated with British gangster films to this day. But in the decades after Get Carter, the genre had been associated with a vérité aesthetic.

Even so, every few years Get Carter is re-released onto British screens and savored by audiences, who are no doubt surprised by the particular bitterness of this pill. In a tale of casual sex and downright sadistic murders, Carter is a melancholic, red-blooded killer exacting his revenge, but he does it with Caine’s unique ability to appear remote and charismatic at the same time. Get Carter is unlike the easily accessible, rather unchallenging, but no less entertaining subsequent entries in the genre, in that it confronts the viewer with Carter’s unflinching cruelty in his determination. The character’s singular persona stands at a distance from any standard or accepted forms of British cultural identity, and so he remains an object of curiosity and fascination exceptional in that culture, yet visceral even for American viewers. What continues to make Get Carter endure is this: Although it’s easy to cheer for Ritchie’s string of tough guys and real RocknRollas, Carter commands our respect in the same manner as an unforgiving force of Nature that we both fear and admire.

(Editor’s Note: This review was commissioned on Patreon. Thank you for your support, Alex!)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review