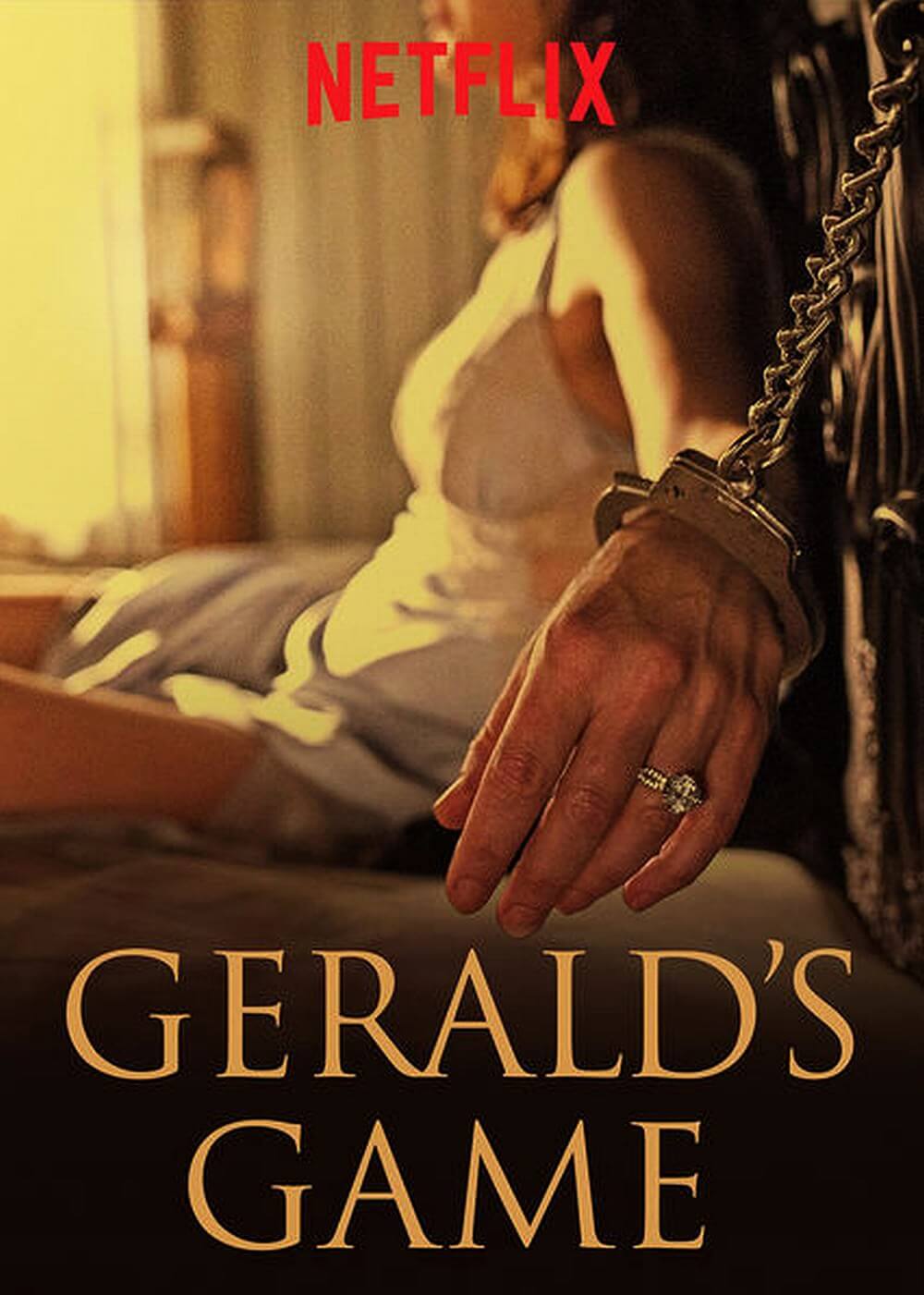

Gerald’s Game

By Brian Eggert |

In the last few years, Hollywood has produced several high-profile adaptations of Stephen King’s most popular novels, and in some cases, big and small screen versions had already been made. The 2017 and 2019 chapters of Andy Muschietti’s It franchise earned hundreds of millions at the box-office between them, reminding viewers of their innate fear of clowns, even though the surface-level adaptations failed to resonate as much as the televised miniseries from 1990. Also in 2017, Sony finally brought King’s fantasy series The Dark Tower to the screen and, though it had lofty potential as an ongoing franchise and featured stars Idris Elba and Matthew McConaughey, it was virtually laughed out of theaters. King’s scariest novel, Pet Sematary, was once again brought to the screen this year, some twenty years after Mary Lambert’s dull adaptation, earning oodles of cash in spite of its unsatisfying execution. Though Hollywood has renewed its interest in the Stephen King brand, it seems unwilling to thoughtfully translate the author’s meandering prose, which so essentially delves into the minds of his characters to make otherwise absurd situations seem plausible.

While major studios throw millions of dollars at large-scale adaptations of King’s most iconic written work, the streaming service Netflix produced the best adaptation in recent years with Gerald’s Game from 2017. In almost every respect, it’s a comparatively smaller-scale film next to Hollywood’s multiplex adaptations. A tense chamber thriller about a woman trapped handcuffed to a bed after a kinky sex game with her husband went horribly wrong, the story takes place almost entirely in the mind of the protagonist. Its director, Mike Flanagan, once described the material as unfilmable, and rightfully so. After all, it’s a tale of suppressed memories coming to the fore, visualized hallucinations, and possibly imagined figures looming in the shadows. Maybe Flanagan saw Danny Boyle’s 127 Hours (2010) since first reading the book in college. After all, there’s a striking similarity between Aron Ralston’s real-life experience in 2003 and the pulpy, fictionalized one written by King in 1992. They both involve the mental process that leads to their respective heroes breaking free of their literal and psychological entanglements.

In an attempt to “spice things up, push a few boundaries” in the bedroom, Jessie (Carla Gugino) and her older husband Gerald (Bruce Greenwood) head to their lakehouse to save their sexless marriage. The disparity between their expectations for the next few days is apparent in the first shots: Jessie packs a sexy silk nightgown, while Gerald packs two sets of no-bullshit handcuffs. Once they arrive, they move into the bedroom so quick that they forget to shut the front door. Jessie prepares herself, lying on the bed in her slip, and Gerald emerges with his handcuffs, having primed himself with a dose of Viagra. But after Gerald locks his wife to the bedposts, the playful bondage devolves into his rape fantasy. About the time he tells Jessie to call for help and refers to himself as “daddy,” she kicks him off, demanding to be set free. Their sex life and marriage seem to be over in the same instant—the very instant that Gerald has a heart attack and falls dead onto his shackled wife.

What ensues is a series of delusions and mental progressions, coupled by a touch of grotesque horror, that unfolds in a limited visual space. The screenplay by Flanagan and Jeff Howard indicates that the writers have thought about King’s book and have done more than just turn the written page into visuals—this is a true adaptation, with full consideration of how the story could best be told on the screen. In written form, Gerald’s Game has a stream of consciousness quality; it’s a patchwork of random thoughts that, in their entirety, build toward an entire experience. Rather than use the cinematic faux pas of constant narration, the writers have turned Jessie’s inner dialogue into figurative elements, and Flanagan visualizes the voices in Jessie’s head. Though his corpse is soon kicked onto the floor at the foot of the bed, Gerald’s phantom stands up, as if a portion of her unconscious mind has split. Likewise, a more composed, rational version of herself appears. These voices occasionally interact and debate each other on how Jessie should proceed to escape. Also, a stray and hungry dog tiptoes into the bedroom, sniffing at Gerald’s corpse. And there’s a dark figure, here dubbed the “Moonlight Man,” who may or may not be a personification of Death, in the form of a giant who carries a bag of bones and jewelry.

What ensues is a series of delusions and mental progressions, coupled by a touch of grotesque horror, that unfolds in a limited visual space. The screenplay by Flanagan and Jeff Howard indicates that the writers have thought about King’s book and have done more than just turn the written page into visuals—this is a true adaptation, with full consideration of how the story could best be told on the screen. In written form, Gerald’s Game has a stream of consciousness quality; it’s a patchwork of random thoughts that, in their entirety, build toward an entire experience. Rather than use the cinematic faux pas of constant narration, the writers have turned Jessie’s inner dialogue into figurative elements, and Flanagan visualizes the voices in Jessie’s head. Though his corpse is soon kicked onto the floor at the foot of the bed, Gerald’s phantom stands up, as if a portion of her unconscious mind has split. Likewise, a more composed, rational version of herself appears. These voices occasionally interact and debate each other on how Jessie should proceed to escape. Also, a stray and hungry dog tiptoes into the bedroom, sniffing at Gerald’s corpse. And there’s a dark figure, here dubbed the “Moonlight Man,” who may or may not be a personification of Death, in the form of a giant who carries a bag of bones and jewelry.

Jessie’s projections may help her reason out the situation, guiding her through how to gain access to water and eventually free herself from the cuffs, but they also bring about several realizations. The sheer trauma of the situation stirs up all manner of memories and associations in the grandly sentimental way that King’s narratives often do. First comes the awareness that Gerald is a misogynist, and perhaps he has always been a misogynist who’s willing to tell jokes such as, “What is a woman anyway? A life support system for a cunt.” Next comes a memory from Jessie’s childhood as a 12-year-old girl, where, during a solar eclipse (the same one King wrote about in the similarly rape-themed Dolores Claiborne), her father (Henry Thomas) manipulates and abuses her. It’s a haunted sequence, shot like a half-imagined dream under the red eye of the eclipse. But the trajectory of the story follows Jessie’s full awareness of the pattern of abusive, fatherly men in her life, and thus her liberation from them. And while some of the symbolism and dialogue here may seem obvious or convenient, it’s no less dramatically resounding when the climactic and stomach-churning scene of escape finally takes place.

Flanagan’s direction is superb. Gerald’s Game is a film that looks like it was storyboarded, and that those storyboards were followed in every detail. Not until the final coda of the film—when Jessie’s self-actualization plays like the keynote by a motivational speaker, followed by a silly last shot of our hero walking defiantly down the middle of the street—is there evidence of a misstep. Jessie reads aloud, via voiceover, a letter to herself that puts too fine a point on the story’s themes. Nevertheless, Flanagan has steered two career-best performances from Gugino and Greenwood. The former must operate under physically limited conditions, evoking an impressive emotional range (everything from anxiety to panic to the tears of an abused child) in a stationary position. Gugino embodies the growth of her character from trophy wife to an independent woman capable of self-preservation to gory, gut-wrenching extremes. Alternatively, without cuffs to restrain him, the mostly shirtless Greenwood brings his misogynist to life. In one incredible extended shot, the actor delivers a punishing monologue about why Jessie should resign herself to death—it’s a masterful choice on Flanagan’s part to leave the scene intact, and a stirring delivery from an actor that should have been a leading man.

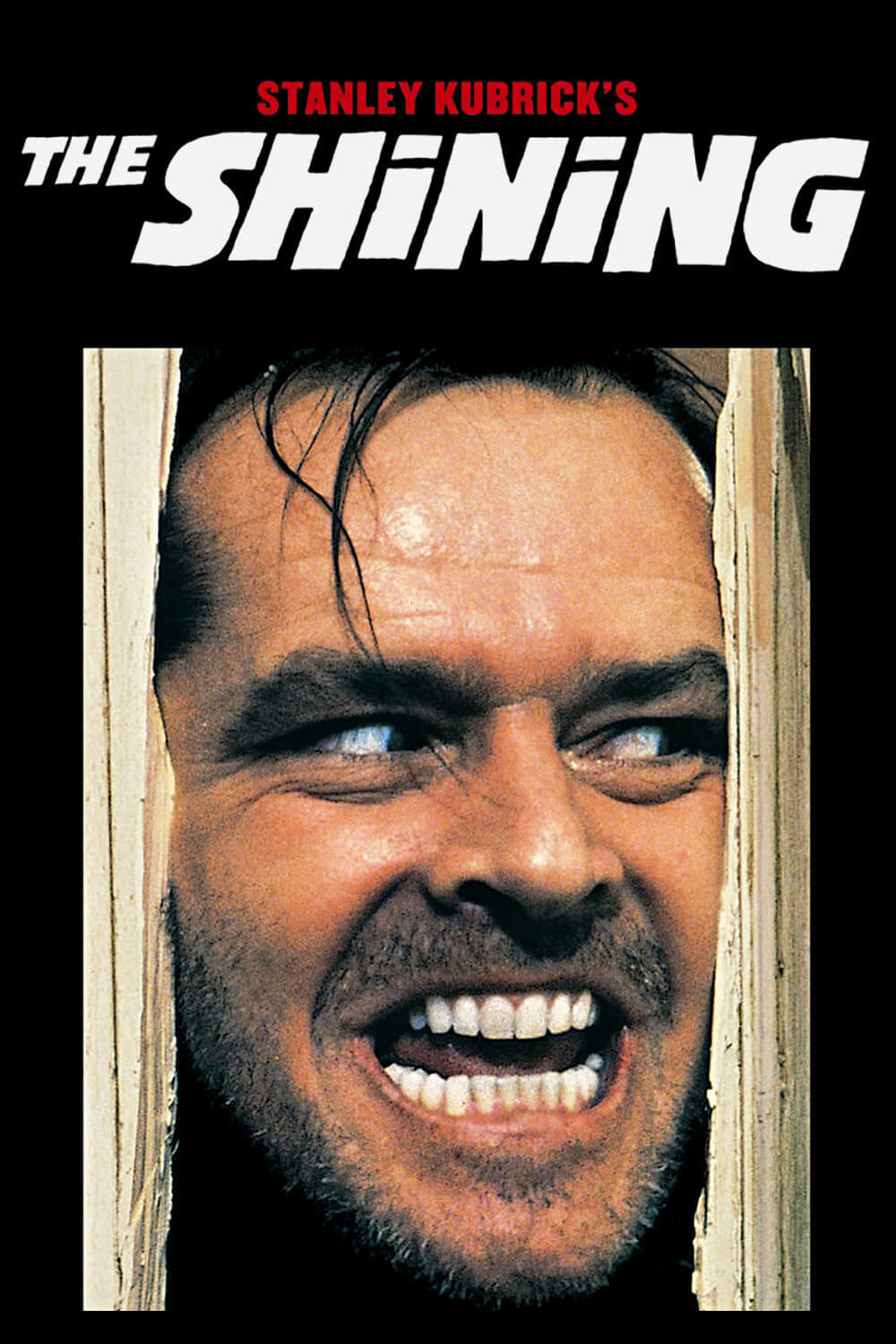

Flanagan is relatively new on the scene. With a small but impressive body of work, he has shown himself to be a filmmaker who elevates horror by exploring themes of grief and trauma among complex characters. His earlier films—Absentia (2011), Oculus (2013), Hush (2016), Before I Wake (2016)—show a craftsman developing his voice. But he made his first fully formed work of psychological and supernatural horror with Ouija: Origin of Evil (2016), a great prequel to a terrible movie. Later, the Netflix limited series The Haunting of Hill House (2018) demonstrated his rich sense of character, combined with supernatural trappings that enhance the overall genre appeal. Gerald’s Game is his best work, and it far exceeds any of the recent King adaptations purveyed by Hollywood. It’s a fully realized and intentional piece of filmmaking that, like the best King novels, both makes the viewer squirm and raises our compassion. It may subject Flanagan’s upcoming Doctor Sleep, the sequel to King’s The Shining, to unreasonable expectations, but even so, it belongs on a shortlist of faithful and thrillingly made King adaptations.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review