Gemini Man

By Brian Eggert |

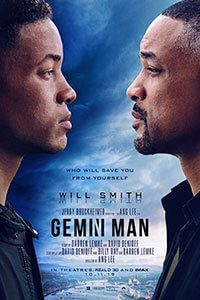

The spirit of the ‘90s is alive in Gemini Man, a high-concept action movie starring Will Smith. In the tradition of outlandish shoot-em-ups such as Face/Off (1997), the movie pits a deadly hired gun against his mirror image. Between his roles in Independence Day (1996) and Men in Black (1997), no blockbuster star was more prominent in the 1990s than Smith. He stars as a government hitman who, upon retirement, is targeted for execution by a younger clone of himself. The actor plays both roles, the younger one rendered with de-aging computer animation to create a Fresh Prince of Bel Air-era performance—a nostalgic look, to be sure. Gemini Man strives to recapture Smith’s glory days with the uncanny special effect, while also supplying a throwback actioner similar to Bad Boys (1995). Moreover, Jerry Bruckheimer, another ‘90s icon, serves as producer for director Ang Lee. Together, they conjure the Hollywood heyday of John Woo here, delivering the sort of bullets-over-brains material filled with inane dialogue, obvious symbolism, operatic slow-motion shootouts, and motorcycle fights.

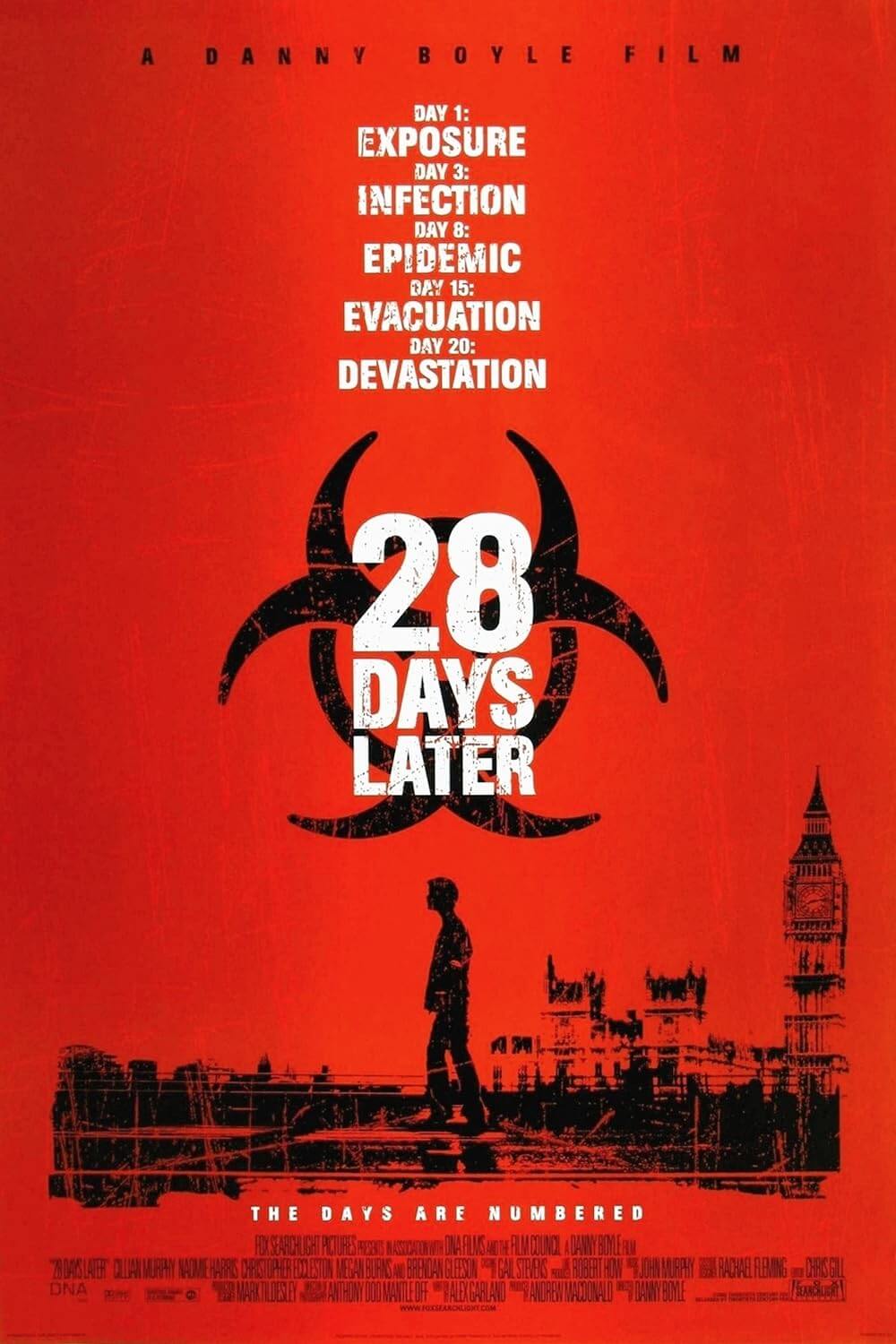

The use of de-aging technology has supplied Gemini Man with an ample promotional tool, giving the Paramount Pictures promotional department a chance to Photoshop not just one but two Will Smith heads onto the movie poster. It’s an effect employed by the MCU and even Martin Scorsese’s latest crime epic, yet it remains an imperfect tool that never quite convinces. If that wasn’t enough, Lee has even more technological tricks up his sleeve. He once again (after Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk in 2016) shoots using a high frame rate (HFR), an unproven gimmick that enhances the typical frames per second (fps) from 24 to 60 or even 120 fps, depending on what’s offered by your local multiplex. The device is meant to make everything onscreen appear more realistic, though the images often end up looking like an episode of Masterpiece Theater. After watching Peter Jackson’s The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey (2012) at 48 fps and finding myself unable to settle into the experience, it’s safe to say the result is jarring and even a hindrance, much like 3D, and not for me. Accordingly, this review refers to the standard 24 fps version.

Still, these visual bells and whistles fail to distract from Gemini Man’s by-the-numbers screenplay by David Benioff, Billy Ray, and Darren Lemke—a story utterly devoid of surprises or any emotional consequence. Smith stars as Henry Brogan, a 51-year-old assassin who recognizes that he’s past his prime for America’s Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA). A lone wolf, Brogan has chronic nightmares about his countless victims, no personal relationships, and has started to develop a conscience. Even so, he somehow manages to be as cheery as most of Smith’s ‘90s-era characters. Anyway, Brogan’s plan to retire equates to trouble for his DIA overseers, namely his former associate, Clay Verris (Clive Owen). Owen is hammy as a cartoonish heavy whose “Gemini Project” has a solution to circumvent the reflection and morality that comes with old age: he creates “a new breed of soldier” by cloning Brogan. Verris has raised the resultant test tube baby as his own, even giving him a cute name, Junior. But the clone character is a hollow-eyed and dubious creation of CGI painting that only occasionally looks like a 20-year-old version of Smith.

The writers heavy-handedly embed themes and symbolism into Gemini Man, reflecting the title with its use of mirrors, mortality, and fathers and sons. Of course, Brogan sees himself in Junior—a naive copy yet-uncorrupted by years of psychological compartmentalization. “He’s the mirror you don’t want to look into,” says Danny (Mary Elizabeth Winstead), a young agent who, when she’s not pointing out the obvious, helps Brogan escape the clutches of his double and the DIA. They’re also joined by the chummy Baron (Benedict Wong), a pilot character underused as comic relief. The action inevitably brings Brogan and Junior face-to-face with gunplay and motorcycle chases, and the symbolism of the protagonist meeting his younger self amid catacomb skulls couldn’t be more overt. Similarly, Brogan’s abandonment and daddy issues come to the fore as a reason for his self-imposed isolation and choice of métier. As it turns out, Verris has been a lousy father to Junior, and Brogan isn’t opposed to taking up the job as a symbolic, saw-it-coming-an-hour-ago second chance.

The writers heavy-handedly embed themes and symbolism into Gemini Man, reflecting the title with its use of mirrors, mortality, and fathers and sons. Of course, Brogan sees himself in Junior—a naive copy yet-uncorrupted by years of psychological compartmentalization. “He’s the mirror you don’t want to look into,” says Danny (Mary Elizabeth Winstead), a young agent who, when she’s not pointing out the obvious, helps Brogan escape the clutches of his double and the DIA. They’re also joined by the chummy Baron (Benedict Wong), a pilot character underused as comic relief. The action inevitably brings Brogan and Junior face-to-face with gunplay and motorcycle chases, and the symbolism of the protagonist meeting his younger self amid catacomb skulls couldn’t be more overt. Similarly, Brogan’s abandonment and daddy issues come to the fore as a reason for his self-imposed isolation and choice of métier. As it turns out, Verris has been a lousy father to Junior, and Brogan isn’t opposed to taking up the job as a symbolic, saw-it-coming-an-hour-ago second chance.

The sheer amount of CGI required to accomplish the de-aged image of Smith, not to mention the HFR, makes almost every moment of Gemini Man difficult to watch. Because of the challenges around both effects, cinematographer Dion Beebe had to light scenes in a way that leaves backgrounds appearing detached from the characters in the foreground. And since Lee, ever the experimenter, wants to showcase his de-aging effect, he employes a series of Jonathan Demme-style close-ups with characters looking into the camera. But the effect wavers—it sometimes looks about right, and sometimes it appears frighteningly unrealistic with Junior’s soulless eyes. (“A doll’s eyes,” to quote a particular shark hunter.) In any case, the viewer is always aware of the trick, and the character of Junior proves so underdeveloped that he has no hope of overcoming the effect. The CGI also seeps into the otherwise engaging scenes of action. During a hand-to-hand combat fight between Brogan and Junior, the two characters look like computer-things beating on each other. In the age of Mission: Impossible – Fallout (2018) and Tom Cruise’s stunt realism, the artificial quality of the action, complete with animated faces over the stuntmen operating the motorcycles, is a disappointment.

At every turn, it seems that Lee has allowed the form to dictate the function of the story, which is counterintuitive. Formal elements from the lighting to the staging of action sequences serve the technology, not the narrative. But Gemini Man has such a hackneyed script that no amount of eye-popping special effects could overshadow the predictable scenario and glib dialogue. It’s the sort of movie that follows the basic rules of screenwriting with dull adherence, resulting in shockless twists and a laughable case of Chekhov’s bee sting. The material reeks of 1990s flair, from the hitman-versus-hitman scenario of Assassins (1995) to the cloned supersoldiers of Judge Dredd (1995). And much like a ‘90s actioner, there’s a noticeable amount of product placement. Characters frequently engage in banal conversation over a conspicuously placed can of Coke, Budweiser, Stella Artois, or Wellington water crackers (an entire scene in the finale could be a commercial in which Brogan tells another character to have a Coke instead of drinking alcohol). Lee and Bruckheimer have drained the material of any life, as storytelling remains secondary (even tertiary) to Gemini Man’s need to sell supermarket goods and make so-called advances in film technology. It’s a lifeless experiment and a restless two hours.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review