Reader's Choice

Gattaca

By Brian Eggert |

In Andrew Niccol’s feature debut, Gattaca, the writer-director crafts a paranoid, discriminatory world out of ripped-from-the-headlines science. Adopting a noirish mood amid an austere dystopian backdrop, it’s the sort of Orwellian vision that could only exist in a movie. Every detail—including the sleek production values, retrofuturist designs, and character constructions—explores the dangers of eugenics. Indeed, Niccol’s film involves a world so obsessed with genetic perfection and eliminating any unwanted hereditary flaws in a lab that its society has been completely reshaped around this premise. Released in 1997, the film tapped into society’s fear of genetic tampering that followed the launch of the Human Genome Project in 1990, rampant discussion of cloning throughout the decade, and prescient fear of gene editing long before the recent births of CRISPR babies. But Gattaca operates better on world-building and conceptual levels than on narrative terms. While initially thought-provoking, it’s the sort of setup that prompts the viewer to nitpick afterward. The film raises questions without convincing answers, and ultimately, it proves only superficially interested in its characters and is compelled instead by intriguing concepts.

The New Zealand-born Niccol spent a decade directing commercials before making his feature debut with Gattaca, launching a trend in his work of exploring science-fiction scenarios as vast social problems that penetrate every facet of his on-screen dystopias. For instance, his 2011 feature In Time stars Amanda Seyfried and Justin Timberlake in a capitalist society where the currency is time, and mortality depends on a countdown clock with a financial component—the more currency you have, the more longevity you can buy. The heroes attempt to crash the system controlling so many lives, and, while navigating countless time-related puns, they confront those who remain in power because of their longer expiration dates. Anon (2018), another Niccol film starring Seyfried, takes place in a future dominated by constant surveillance from government-mandated recording devices implanted into the eyes of every living person. Seyfried’s character finds a way to block herself from being recorded, recognizing that power lies in denying access. In each case, Niccol creates a high-concept world where the extreme integration of technology reshapes social hierarchies—a setup reminiscent of many 1970s sci-fi movies, such as Soylent Green (1973) and Logan’s Run (1976), and episodes of Black Mirror. However, he rarely explores his premises in satisfying emotional ways.

As a result, it’s easy to get caught up in the neat world Niccol has constructed. Set in the “not-too-distant future,” Niccol’s social dynamic in Gattaca is the most well-realized of his concepts. A new family planning measure allows parents to subject unborn children to genetic screenings, adhering to a society obsessed with eliminating genetic imperfections and socially undesirable traits. Not only does the screening process remove unwanted conditions, such as heart disease or depression, but it creates an almost superhuman population of bioengineered people who also happen to look like cover models and behave like robots. Thus, the film’s society has been segmented into two distinct groups. Valids, whose genes have been screened by geneticists for perceived flaws and defects before birth. Invalids, however, have not been screened and may have a higher risk of genetic weaknesses or medical conditions. Valids receive the best jobs and higher pay, whereas Invalids occupy the lowest rungs on the social ladder. The ideals of this society extend from scientists to corporate hiring—even social interactions. One scene in the film depicts a woman vetting a potential suitor by checking his genetic makeup, taken from the residue of a recent kiss, at a convenient kiosk.

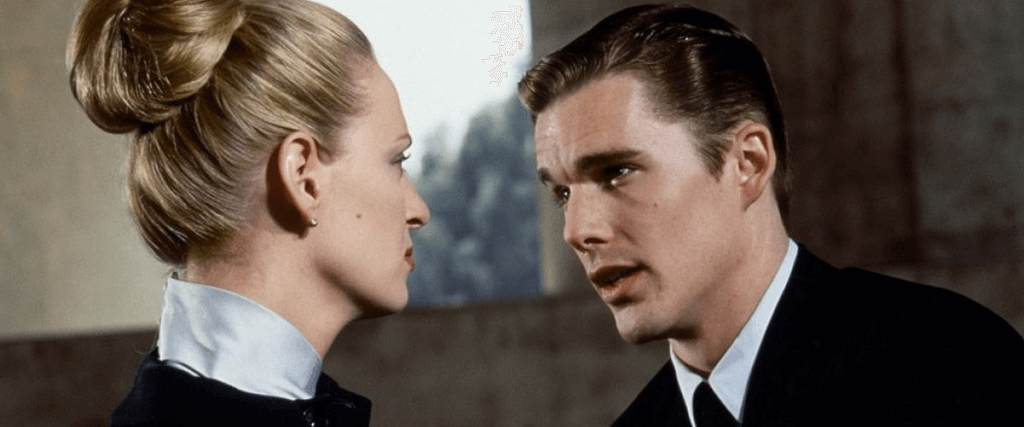

In the world of Gattaca, a person’s genes encapsulate their potential. But the film’s protagonist, played by Ethan Hawke, named Vincent Freeman—one of Niccol’s many on-the-nose touches—defies such “genoism.” An Invalid with a heart defect, Vincent aspires to be an astronaut at Gattaca headquarters (actually Frank Lloyd Wright’s Marin County Civic Center), an elitist company whose exploratory shuttles launch daily. But Gattaca practices the strictest genoism, evidenced by the orderliness and uniformity of their workforce—predominantly upper-class Valids who look and dress the same. They have also adopted the ideal of cleanliness (it’s “next to godliness”), as an outward symbol of their genetic perfectionism. As an Invalid, Vincent could never pass their screening process, which considers future employees according to their genetic makeup, using a urine test in place of a job interview. Gattaca even prohibits Invalids from entering their building with mandatory blood scans at the entrance. And while discrimination based on genes remains illegal, as Vincent’s voiceover explains, it’s a common practice. These obstacles require that Vincent adopt the genetic identity of Jerome Morrow (Jude Law), a Valid and former Olympic athlete who was rendered a paraplegic after a car accident, so Vincent can work his dream job under Jerome’s name at Gattaca in a form of criminal passing.

In the world of Gattaca, a person’s genes encapsulate their potential. But the film’s protagonist, played by Ethan Hawke, named Vincent Freeman—one of Niccol’s many on-the-nose touches—defies such “genoism.” An Invalid with a heart defect, Vincent aspires to be an astronaut at Gattaca headquarters (actually Frank Lloyd Wright’s Marin County Civic Center), an elitist company whose exploratory shuttles launch daily. But Gattaca practices the strictest genoism, evidenced by the orderliness and uniformity of their workforce—predominantly upper-class Valids who look and dress the same. They have also adopted the ideal of cleanliness (it’s “next to godliness”), as an outward symbol of their genetic perfectionism. As an Invalid, Vincent could never pass their screening process, which considers future employees according to their genetic makeup, using a urine test in place of a job interview. Gattaca even prohibits Invalids from entering their building with mandatory blood scans at the entrance. And while discrimination based on genes remains illegal, as Vincent’s voiceover explains, it’s a common practice. These obstacles require that Vincent adopt the genetic identity of Jerome Morrow (Jude Law), a Valid and former Olympic athlete who was rendered a paraplegic after a car accident, so Vincent can work his dream job under Jerome’s name at Gattaca in a form of criminal passing.

To carry out the required deception, Vincent works with an underground agent named German (Tony Shalhoub)—a name that evokes thoughts of Nazism and its fixation on eugenic and racial purity. Hungarian scholar Anna Petneházi points out the film’s “direct references to the dark heritage of eugenics programs which made racial hygiene and the ‘treatment’ of genetic impurity a pivotal element of (bio)political practices.” Whereas natural evolution may improve genes over time without human intervention, eugenics attempts to apply a specific gene goal according to a particular human agenda. For example, Nazis shaped the body politic according to their discriminatory ideology, carrying them out with the creation of concentration camps and the Final Solution. Niccol suggests that pre-birth tampering with genes to achieve an idealized form is tantamount to discrimination according to race, furthered by Gattaca’s hope to find the “right kind” of people according to their genes. Moreover, Petneházi notes “the underlying connections between the capitalist and eugenic production of the body through its biologization and commodification.” Indeed, every trait of a Valid’s body can be engineered according to their parents’ specifications, leaving no detail to chance. Therefore, each attribute registers as a separate, commodified choice. When Vincent undergoes a urine test at Gattaca, the geneticist on staff (Xander Berkeley) casually remarks on the size of Vincent’s penis, as though he’s commenting on a customizable automobile part—it’s not so much a part of Vincent’s body as an option selected at the point of sale.

One could go on and on about the details of Niccol’s world-building and the rules of his society, how constant genetic screenings require Vincent to scrape excess skin cells and hair from his body, or how he must conceal Jerome’s blood and urine on his person in case of a random scan. Such details amount to an elaborately conceived science-fiction premise, naturally embedded with universal and dramatically involving themes about the underclass defying an oppressive elitist system. But Gattaca remains characteristic of Niccol’s genre work in that his concepts often outweigh his interest in characters and sometimes even narrative logic. Take Vincent’s singular desire to explore space. It’s a passion that requires him to break laws and commit frauds as a “borrowed ladder”—someone who uses another’s genetic identity to move up the societal ladder. But there’s no particular reason for Vincent’s desire, other than choosing an objective that allows him to defy the discriminatory system that considers him incapable. He is singularly focused on a mission to Titan, the largest of Saturn’s moons, but his motivations remain underdeveloped by Niccol’s script. Instead, Vincent’s goal is merely a pretense for Niccol to concoct a thriller around his concept.

A murder at Gattaca prompts an investigation overseen by two detectives, played by Loren Dean and Alan Arkin. The police presence puts Vincent on alert. They scan for loose skin cells and hairs and screen employee urine and blood for a potential Invalid presence—emphasizing their prejudice linking the so-called genetically inferior to criminal behavior. When Arkin’s detective vows to “round up the usual suspects,” he means Invalids. While these scenes create tension around Vincent’s secret and possible exposure, they also draw from genre conventions. The framework of Niccol’s narrative blends science fiction with the tonality of film noir, apparent in Gattaca’s red herrings, reserved emotions, serious mood, and Vincent’s predominant narration, most of which supplies a continuous stream of expositional information. Niccol’s noir influences inform the film’s look as well. Costume designer Colleen Atwood dressed the detectives in long coats reminiscent of noir characters, while Gattaca employees wear almost identical suits, underlining their sameness. Atwood’s throwback designs and clean lines accompany the sharp clarity of Jan Roelfs’ production design, which has the hygienic look of a utopia, albeit with futuristic electric cars that borrow 1960s designs.

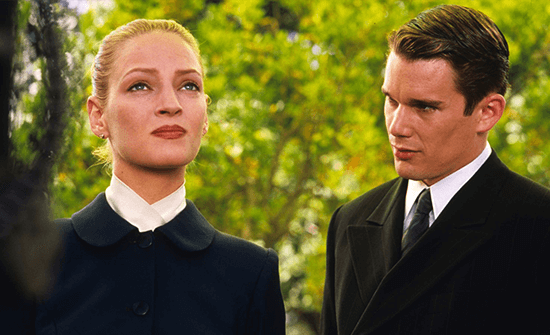

Fortunately for Vincent, Niccol delivers an ending that’s more hopeful than a film noir finale might’ve been. His true identity as an Invalid remains a secret, partly because his estranged brother Anton, a Valid, is the primary detective on the case. The penis-regarding geneticist also buries evidence of Vincent’s true identity in a late scene, having hinted several times throughout the movie, much to Vincent’s obliviousness, that his son, too, is an Invalid. He’s been aware of Vincent’s deception all along. However convenient these details may seem, they underscore the class warfare between Valids and Invalids, dramatically crystallized by Anton and Vincent’s sibling rivalry, with Anton resentful about Vincent’s ability to defy his projected 30-year lifespan. More engaging is a romantic subplot involving Irene (Uma Thurman), a Valid who doubts herself because of her elevated risk of heart disease. Thurman’s twitchy, uncertain performance hints at the rigorous genetic paranoia created by Niccol’s world, even if her character feels underserviced as a romantic interest. In one of his first major film roles, Law gives a nuanced turn as a Valid whose genetic potential was destroyed in a car accident, and therefore, he feels robbed of his Valid life. Gore Vidal, Ernest Borgnine, Blair Underwood, and Elias Koteas also make brief appearances.

Fortunately for Vincent, Niccol delivers an ending that’s more hopeful than a film noir finale might’ve been. His true identity as an Invalid remains a secret, partly because his estranged brother Anton, a Valid, is the primary detective on the case. The penis-regarding geneticist also buries evidence of Vincent’s true identity in a late scene, having hinted several times throughout the movie, much to Vincent’s obliviousness, that his son, too, is an Invalid. He’s been aware of Vincent’s deception all along. However convenient these details may seem, they underscore the class warfare between Valids and Invalids, dramatically crystallized by Anton and Vincent’s sibling rivalry, with Anton resentful about Vincent’s ability to defy his projected 30-year lifespan. More engaging is a romantic subplot involving Irene (Uma Thurman), a Valid who doubts herself because of her elevated risk of heart disease. Thurman’s twitchy, uncertain performance hints at the rigorous genetic paranoia created by Niccol’s world, even if her character feels underserviced as a romantic interest. In one of his first major film roles, Law gives a nuanced turn as a Valid whose genetic potential was destroyed in a car accident, and therefore, he feels robbed of his Valid life. Gore Vidal, Ernest Borgnine, Blair Underwood, and Elias Koteas also make brief appearances.

Other details about Niccol’s conception feel less considered and representative of the writer-director not fleshing-out his ideas. Why, for instance, do automobiles use green headlights? Why do Gattaca’s astronauts wear three-piece suits into space? Why is a concert pianist born with six fingers on each hand venerated for his aberration in this world obsessed with genetic purities? Or has he been engineered to have extra digits, opening the door for other genetic liberties with the human form? Niccol includes a few details such as these that seem random in the broader set of rules governing the screen story. Elsewhere, he creates moments that seem out of character for Vincent. For example, when Irene discovers his symbiotic relationship with Jerome, Vincent confronts her in a manner that proves disturbing: “How are you, Jerome?” Jerome asks Vincent. “Not bad, Jerome,” responds Vincent, in a moment that feels designed to unnerve Irene. Most of these inconsistencies and oddities go overlooked in place of the slick visual treatment by Polish cinematographer Sławomir Idziak, a regular collaborator with Krzysztof Kieślowski. Idziak’s amber-hued, almost orange-tinged color timing bears a distinct look that gives Gattaca its futuristic character.

Regardless of the occasional plot hole or simplistic character motivation, most critics praised Gattaca for its intelligence and thought-provoking setup. Typical of the critical response, Roger Ebert called it a “thriller with ideas,” and Janet Maslin described it as a “fully imagined work of cautionary futuristic fiction”—though few remarked about its powerful emotions or three-dimensional characters. While the production earned back just over a third of its $36 million budget at the box office, Niccol’s film became popular on the home video market. It also inspired imitators, including 2015’s Equals and Niccol’s subsequent work. Gattaca remains formative for introducing viewers to the concept of genoism with a distinct, precise visual style, whereas its message about defying the expectations thrust upon you—that people can be more than their résumé or genes suggest—proves lasting, if simplistic. Ultimately, the film’s intentional emotional detachment and minimally explored psychology leave the proceedings at a remove and best left to intellectual consideration. The film poses a series of “What if?” questions that Niccol explores with his usual focus on premise over people, albeit captured by an attractive cast, stark visuals, and not altogether satisfying dramaturgy.

(Note: This review was originally suggested and posted to Patreon on January 24, 2023. Thank you for your continued support and patronage, Dustin!)

Bibliography:

Hughes, Rowland. “The Ends of the Earth: Nature, Narrative, and Identity in Dystopian Film.” Critical Survey, vol. 25, no. 2, 2013, pp. 22–39. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/42751032. Accessed 10 January 2023.

Kirby, David A. “The New Eugenics in Cinema: Genetic Determinism and Gene Therapy in ‘GATTACA.’” Science Fiction Studies, vol. 27, no. 2, 2000, pp. 193–215. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4240876. Accessed 10 January 2023.

Petneházi, Anna. “‘Who Can Straighten What He Hath Made Crooked?’: Eugenics and the Camp in Gattaca and The Island.” Hungarian Journal of English and American Studies (HJEAS), vol. 22, no. 2, 2016, pp. 351–70. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26894828. Accessed 10 January 2023.

Rabkin, Eric S. “Science Fiction and the Future of Criticism.” PMLA, vol. 119, no. 3, 2004, pp. 457–73. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25486061. Accessed 10 January 2023.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review