Gambit

By Brian Eggert |

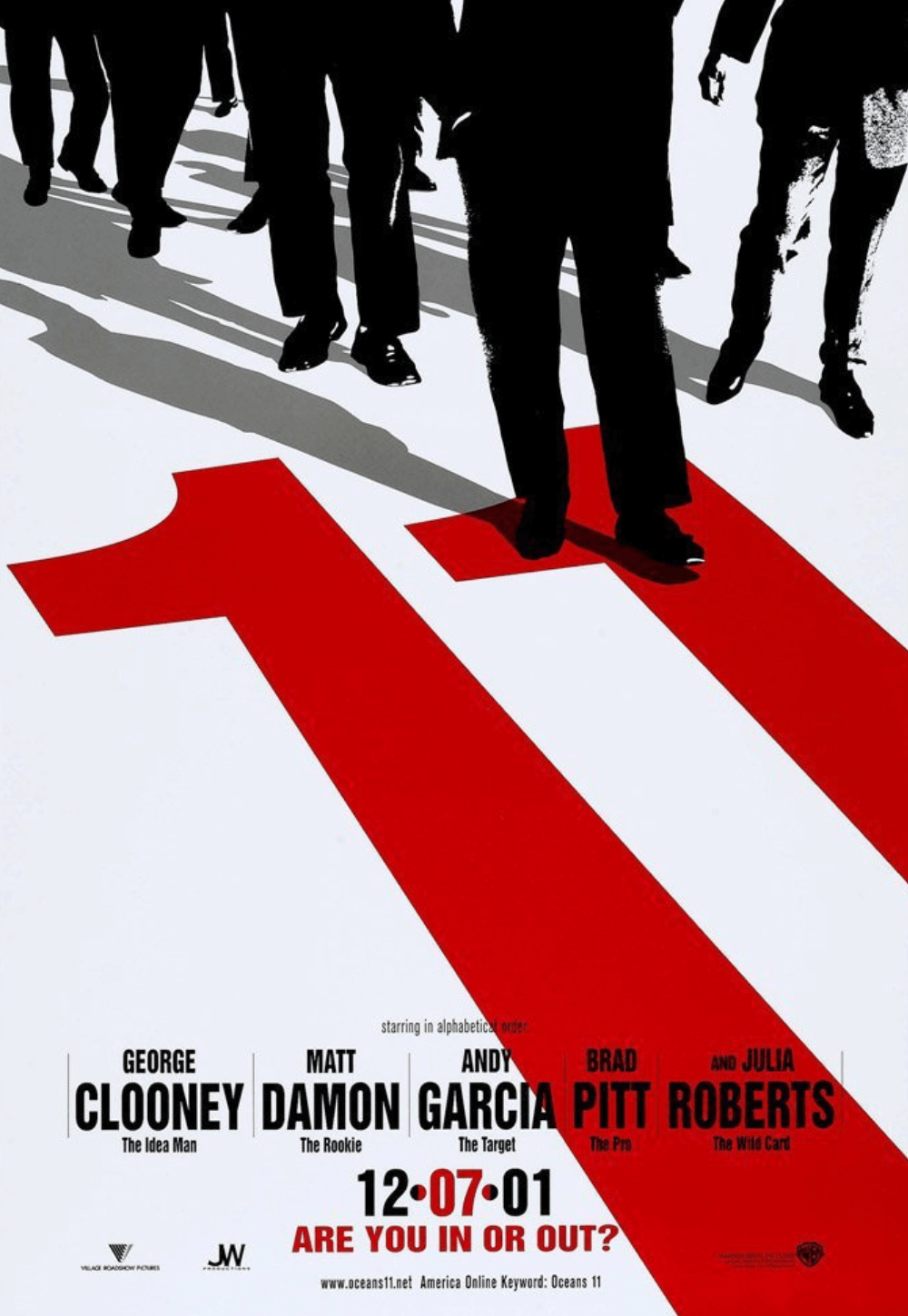

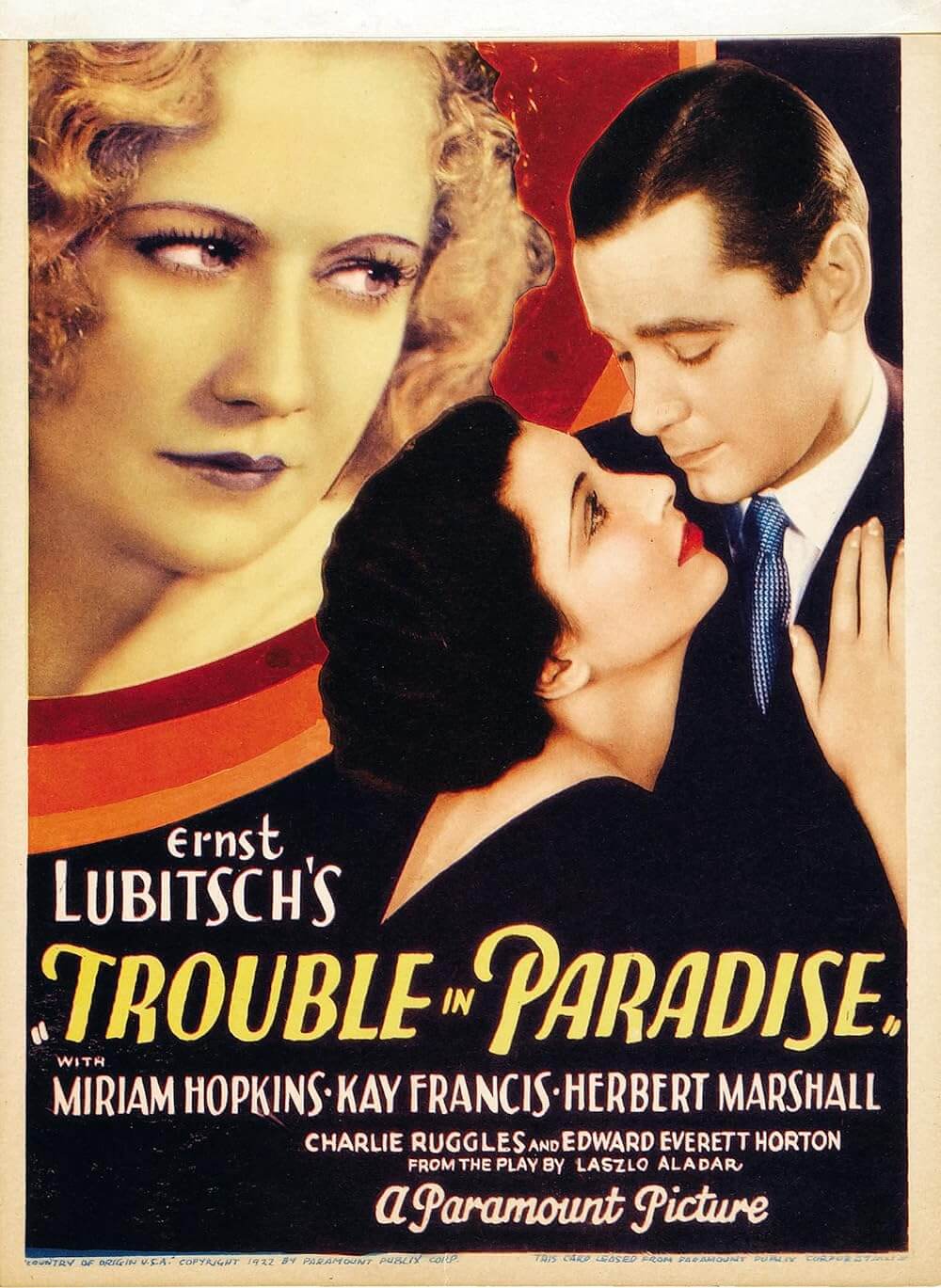

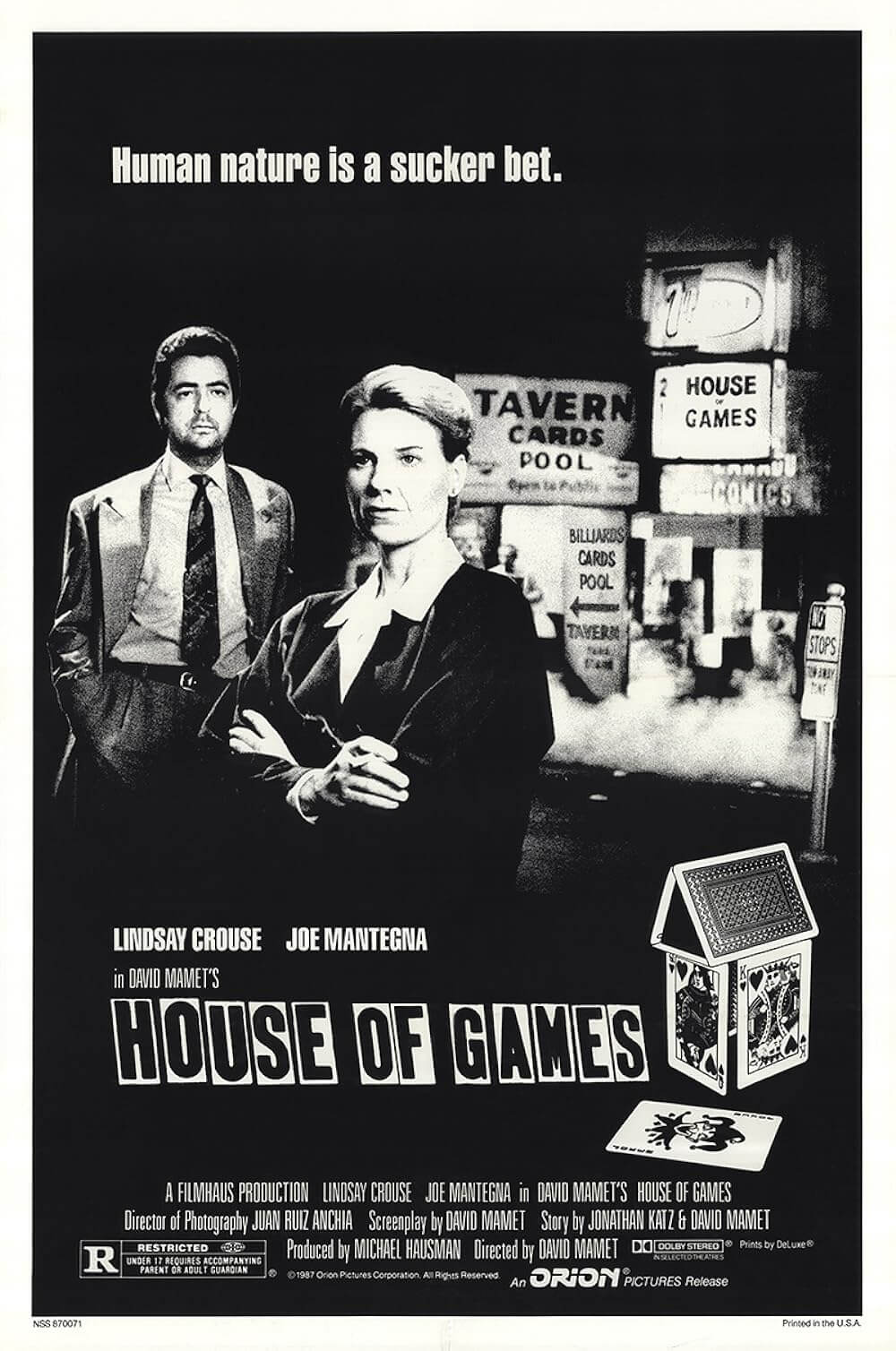

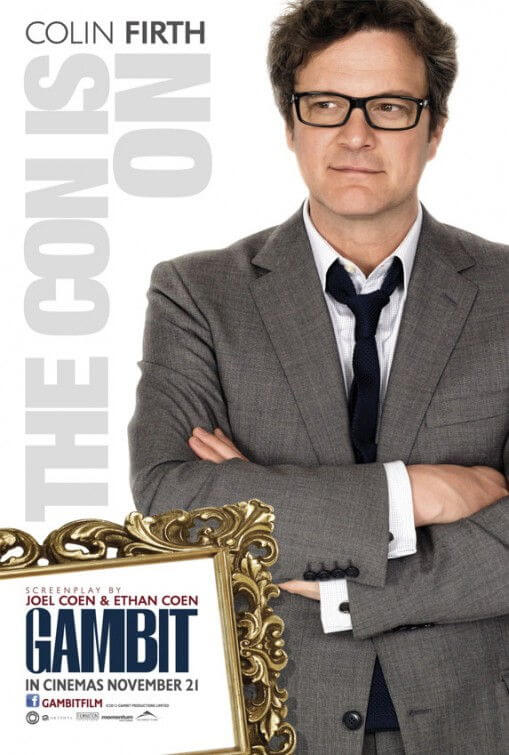

Tedious and juvenile, Gambit boasts a script by the Coen brothers, a promising cast (including Colin Firth, Cameron Diaz, and Alan Rickman), and a twisting scenario ripe with potential. But this light farce becomes tiresome long before its brief 89-minute runtime expires. Remade from Ronald Neame’s comedy from 1966, which starred Michael Caine, Shirley Maclaine, and Herbert Lom, the new film involves art forgeries and elaborate con games—both typically interesting plot elements when combined (see Oceans 12, The Thomas Crown Affair remake, or this year’s The Art of the Steal), especially so when some cinematic verve and attractive stars are added to the mix. Except, Gambit carries a narrow sense of humor ranging from flatulence to shocking racial stereotypes, while everyone behind the camera and in front seems disinterested in the material.

Spearheaded by producer Mike Lobell, a remake of Neame’s mildly enjoyable original has been discussed in Hollywood since the late 1990s, with names like Alexander Payne and Robert Altman cited to direct, while talent from Reese Witherspoon to Jennifer Aniston was in discussions to star. The Coens completed their script back in their lowest of lows, during their Intolerable Cruelty and The Ladykillers days, taking the assignment as writers-for-hire between projects. Fresh off his Oscar for The King’s Speech, Firth’s attachment gave the production legs under director Michael Hoffman, whose work ranges from Soapdish (1991) to The Last Station (2009). The film premiered in the UK in 2012, but poor performance and word-of-mouth ensured its limited theatrical and VOD release stateside—a surprising turn for a picture featuring one Oscar-winner and another box-office draw.

The film opens with an animated title sequence somewhere between those in The Pink Panther (1963) and Catch Me if You Can (2002), and therein gives away the entire plot of the film in animation, forcing us to sit through the kooky hijinks in live-action form. Firth plays Caine’s original role as Harry Deane, an ineffectual art historian who works for a ferocious and boorish media mogul, Lionel Shabandar (Rickman). To dupe Shabandar out of millions and exact revenge for years of humiliating verbal abuse in the office, Deane and his art forger friend, The Major (Tom Courtenay), concoct a plan that will result in Shabandar buying a forged Monet canvas. For reasons not worth explaining in this review, Deane must elicit the help of Texas rodeo star P.J. Puznowski (Diaz), who goes along with the plan without much convincing. Puznowski and Shabandar hit it off. Deane grows jealous, having fallen for Puznowski himself. Antics ensue.

One humorous aside carried over from the original involves a tease in the opening sequence, where Deane’s plan works out to the last detail—Shabandar conveniently takes the bait, and Puznowski’s later-heard motormouth remains silent for the first 10 minutes. Reality spoils Deane’s illusion, and, of course, nothing goes as planned. Take the film’s sole audible laugh, when Deane attempts to check Puznowski into London’s swanky Savoy Hotel, but their endless banter is misunderstood by the hotel’s staff. Not so funny is the broad nationalistic typecasting: A throng of Japanese businessmen talk in horrific accents, dropping their Ls into Rs and engaging in bad karaoke; the British are seen as hoity-toity and incurably stuffy; Americans are exclusively Texan, with twangy accents; playing a German art curator, Stanley Tucci’s accent is so exaggerated that one suspects he’ll be revealed as an American posing as a German, but this is not so.

Achingly unfunny situations try to force laughs out of an unengaged audience, who spends the majority of the film’s runtime wincing at Diaz’s horrendously bad Texan accent. Firth and Rickman are serviceable if unbelievable characterizations. But what can we expect from a farce modeled after 1960s-brand Euro-comedies? By the time Firth stands pantless on a hotel ledge for longer than any such gag should be carried out, Gambit has forced us to wonder how this formless heap ever came from such distinguished authors as the Coen brothers. Certainly, the Coens have delved into the lowbrow territory and slapstick humor with much success in Raising Arizona (1987) or Burn After Reading (2008), but more often than not, within a narrative that has multiple layers and meanings. Never subtle and always over-the-top, nothing about this unnecessary remake suggests anything but a routine and painfully dull “madcap romp” in need of a distinct personality driving the production.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review