Funny People

By Brian Eggert |

Stand-up comics make up a strange, moody group of people. Most have more problems than you might imagine—everything from depression to substance abuse. They tell jokes about their problems for the crowd’s benefit, and then they walk offstage back to their often miserable lives from which they draw that humor. The laughter provides a high, and they crave it like heroin, desperate for another hit so they can laugh away their troubles. This sad clown dynamic, an ebb and flow between the gloomy and the hilarious, provides the structure for Judd Apatow’s third film, Funny People.

More substantial than his previous work on The 40-Year-Old Virgin and Knocked Up, Apatow has written and directed another comedy that’s both dirty-minded yet touching, but it’s more the latter. Except here, the humor is merely the setting for an affecting drama about comedians. Their material is endlessly amusing, and their chummy and sarcastic behavior toward one another riotous. Yet underneath that, Apatow emphasizes how the humor presents a façade. Think about Sam Kinison or Lenny Bruce, how these were singular comic figures who, offstage, were complex personalities. Apatow considers such a personality and finds a wealth of emotional material.

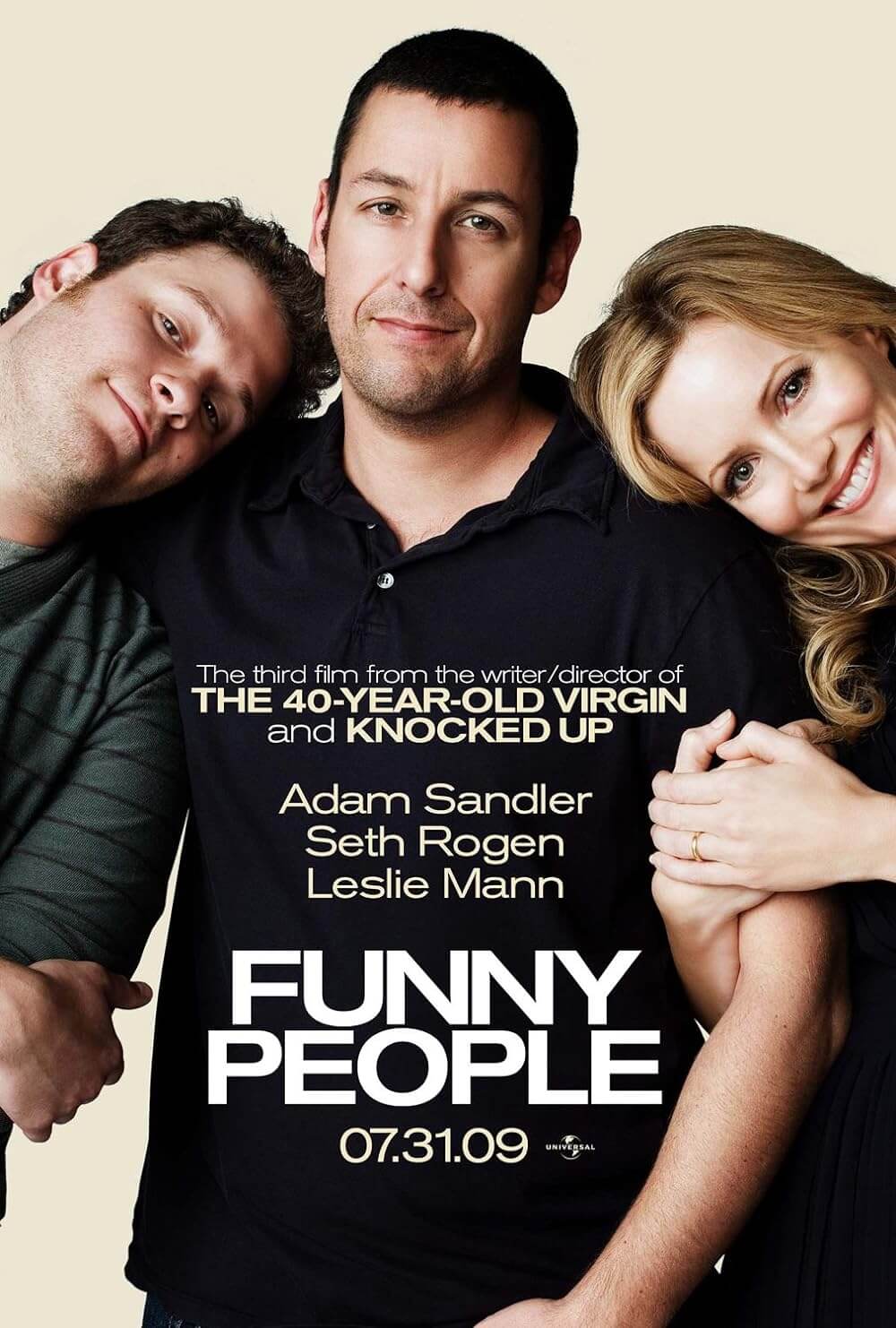

Adam Sandler plays George Simmons, a thinly veiled construct of himself. Simmons began as a stand-up but has since made millions starring in absurd blockbuster comedies, becoming every young act’s idol and aspiration. Simmons lives alone in his massive mansion with no close ties of any kind. When he learns that he might be dying, there’s no one there to comfort or care for him. He reaches into his past—shown through actual vintage tapes of Sandler’s stand-up career and home movies taken from when Apatow and Sandler were roommates—and decides to get back to his origins on the circuit.

There, he meets one of the uncountable struggling comics working improv night, a rookie named Ira (Seth Rogen). Perhaps out of isolation and fear of being alone forever, Simmons asks Ira to write jokes for him and become his personal assistant. They tour small venues together, and ultimately, Ira becomes his confidante, the only person to know he’s dying, and the sole ear to which Simmons can talk about life and comedy. Simmons maintains plenty of walls between them, never wanting to admit they’re friends or that he cares about anyone but himself. Ira, meanwhile, can’t help but care; he cries for his new boss on occasion and shares his sadness with his roommates (Jonah Hill and Jason Schwartzman).

There may be some hope for Simmons’ happiness in Laura (Leslie Mann, Apatow’s wife), an old flame that left when he became a star and couldn’t resist the sexual benefits of being a celebrity. She’s since had two children (played by Apatow’s daughters Maude and Iris) with her husband Clark (Eric Bana), an unfaithful Australian brute who’s left Laura questioning her marriage and vulnerable to Simmon’s new, friend-needy outlook on life. Ira observes as Simmons walks a line between apologizing to an ex-lover and pursuing a married woman as a romantic interest.

When Adam Sandler chooses to act beyond his standard silly voices, his range is really quite surprising. Films like Punch Drunk Love, Spanglish, and Reign Over Me come once every few years, with mindless comedies like Bedtime Stories and You Don’t Mess With the Zohan beating those quality pictures out of our memory, leaving us with a skewed onscreen persona that Sandler will never be able to shake. This is his best, most personal performance, as clearly, he’s playing a version of himself that in some respect, must be true. So while Sandler might not be reflecting on a near-death experience, it’s apparent he’s tapped into a level of himself audiences have not yet seen.

Rogen, too, offers a tender performance that comes unexpectedly from an actor whose roles, even the genial ones, are often nothing more than the lovable stoner. Imagine that, Rogen doesn’t smoke pot once in this film. He’s lost a staggering amount of weight, and he presents himself as shy and awkward. He’s the heart of the movie, fitting in perfectly with the array of stand-up personalities in the back and foregrounds, all of whom wrote their own material for the stage portions of the film. Apatow and Sandler have amassed their laundry list of friends to appear onscreen, some significant names and other faces best recognized on Comedy Central. All of them have had their days in front of the brick wall. Even Bana did some stand-up in Australia before becoming an action star in Hollywood.

The film looks and feels like a drama, not a comedy. Shot by Academy Award-winning cinematographer Janusz Kaminski, whose work includes most of Steven Spielberg’s films in the last decade or so, the result is visually more somber than the brightness of your standard comedy. Funny People has touching insights on this bizarre subculture, populated mainly by guys who talk about masturbating and their members way too much. But compared to the raunchy films produced by Apatow or his earlier directorial efforts, the dirty remarks are toned down for something more significant. Apatow and Sandler imbue a weighty, humanizing depth here, so those expecting a full-on laugh-riot will be sorely disappointed, perhaps even bummed. It’s a drama that just so happens to be about funny people. Certainly, you’ll laugh at their shtick, but you’ll also see their jokes as veils for whatever hides beneath.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review