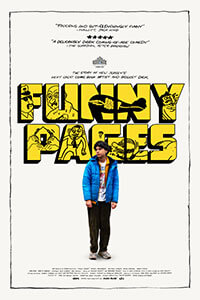

Funny Pages

By Brian Eggert |

(Note: A24 has Funny Pages set for limited release on Friday, August 26. Viewers can also rent the film in A24’s Screening Room on Thursday, August 25.)

Funny Pages takes place in a grubby and begrimed world, similar to those explored in alternative comics. Daniel Clowes’ Ghost World and Art School Confidential were evident inspirations for the story, which follows an aspiring young artist committed to transforming his life into that of an underground comic author. Daniel Zolghadri—best known as the kid from Eighth Grade (2018) who makes a creepy pass at Elsie Fisher—plays Robert, the film’s 17-year-old protagonist who wants to be the next Harvey Pekar or Robert Crumb. Although he comes from a privileged home in a New Jersey suburb, Robert yearns to portray the seedy life depicted in his favorite comics. But what does he know of it? He intends to learn. The film unwinds in dusty comic shops and unseemly basement apartments, and it’s populated by weirdos, perverts, and at least one (and probably more) disturbingly unhinged man. The result isn’t for everyone, but based on the description so far, chances are you know whether you’re interested.

Case in point: If you don’t laugh during the opening scene, then Funny Pages probably isn’t for you. After urging Robert to “always subvert” in his fledgling cartoonist work, the boy’s high school art teacher, Mr. Katano (Stephen Adly Guirgis), climbs on a table and gets buck naked—part of an after-hours lesson about the importance of working from human subjects. If this sounds awkward and creepy, Robert isn’t bothered; he doesn’t seem to mind his mentor’s enthusiasm for life drawing. But afterward, the teacher feels self-conscious and tries to apologize from inside his car while driving the wrong way down a road, and that’s when he dies in a sudden crash. I laughed throughout these scenes; many will not. Although most artists that Robert admires explore the banality of real life in sometimes grotesquely exaggerated ways, Funny Pages goes even further—beyond outlandishness into a cringe-comedy experience that induces as many winces as outright cackles.

Owen Kline, the film’s writer-director—and son of Phoebe Cates and Kevin Kline—seems to have watched a bunch of hilariously scuzzy independent movies from the mid-1990s and decided to replicate them. Watching Kline’s movie, shot on 16mm by cinematographers Sean Price Williams and Hunter Zimny, the viewer notices the intentionally crude style of early Todd Solondz, Terry Zwigoff, or Josh and Benny Safdie. But its scrappy look is addressed later when Miles (Miles Emanuel)—Robert’s best friend stricken with acne, a mane of long frizzy hair, and a simple innocence—asks, “Is form really more important than soul?” It’s an essential question for any artist trying to find their voice or perspective. How much attention should one pay to the technical execution, and how much to meaning? Once Robert asks such questions, his uncertain answers make him desperate to replace the guidance Mr. Katano once supplied.

No wonder Funny Pages was produced partly by the Safdie brothers, since Kline, besides using their regular d.p. (Williams), captures their grainy, delirious aesthetic best seen in their 2008 feature, Daddy Longlegs. There’s reckless energy propelling Robert, such as when he rents a queasily unlivable and windowless basement apartment in Trenton, flashing warning signs galore: the sweaty landlord, Barry (Michael Townsend Wright), stays in the room next door; Robert can’t turn down the sweltering heat; the water is sewage-colored; there’s something strange in the scummy fish tank; and Robert has to share a room with an adult man. Still, Robert isn’t the most practical or discerning guy. After starting an assistant job with a cheery public defender (Marcia Debonis), his face lights up over his first check for $63.41. How he expects to pay $350 for rent is never explained. Perhaps that’s because he knows that his parents (Maria Dizzia, Josh Pais) will always provide a safety net, regardless of thinking his behavior is “brat shit.”

No wonder Funny Pages was produced partly by the Safdie brothers, since Kline, besides using their regular d.p. (Williams), captures their grainy, delirious aesthetic best seen in their 2008 feature, Daddy Longlegs. There’s reckless energy propelling Robert, such as when he rents a queasily unlivable and windowless basement apartment in Trenton, flashing warning signs galore: the sweaty landlord, Barry (Michael Townsend Wright), stays in the room next door; Robert can’t turn down the sweltering heat; the water is sewage-colored; there’s something strange in the scummy fish tank; and Robert has to share a room with an adult man. Still, Robert isn’t the most practical or discerning guy. After starting an assistant job with a cheery public defender (Marcia Debonis), his face lights up over his first check for $63.41. How he expects to pay $350 for rent is never explained. Perhaps that’s because he knows that his parents (Maria Dizzia, Josh Pais) will always provide a safety net, regardless of thinking his behavior is “brat shit.”

Robert’s desperate search for encouragement and validation for his art reaches a low point when he meets Wallace (Matthew Maher) in the public defender’s office. Once he learns Wallace used to work at Image Comics as an assistant color separator, all other alarm bells quiet. But Wallace’s unhinged energy, paranoid eyes, and uneasy relationship with a particular Rite Aid pharmacist, leave the viewer feeling disturbed—not only because Wallace seems to know less than he implies but because Robert places the oddball on a pedestal, and diminishes Miles because he feels like a big shot for knowing Wallace. Though his behavior is confused, Robert’s art reveals hints of his talent for (unconscious?) observation when he pens Wallace into a nervy, maniacal cartoon. The young artist’s talent is already developed and seems to pour out of him in raw, uninhibited work, but he remains lost and uncertain of himself without a guide. What Funny Pages suggests is that artists who create work like Clowes, Crumb, and Pekar never feel at peace with the world or themselves. That’s what their unromantic art is all about.

Distributed by A24 in limited release, the film was also co-produced by Ronald Bronstein, whose grimy feature Frownland (2007) bears a similar embrace of filth and floundering. Despite Kline’s authentic backers, a viewer familiar with the movies, filmmakers, and comic artists mentioned in this review may feel a twinge of faux subversion—as though Funny Pages attempts to approximate an established style rather than undermine conventions, even if through imitation of (or adherence to) an established indie style, Kline subverts the norm anyway. The first-time director—who started as an actor in Noah Baumbach’s The Squid and the Whale (2005), playing a young boy who smears semen on school lockers—searches for his voice by using others as a launchpad, and that’s what Robert does. In that sense, the film is a confident work from a promising artist who is willing to expose his character’s insecurities, desperation, and misguided choices for what they are.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review