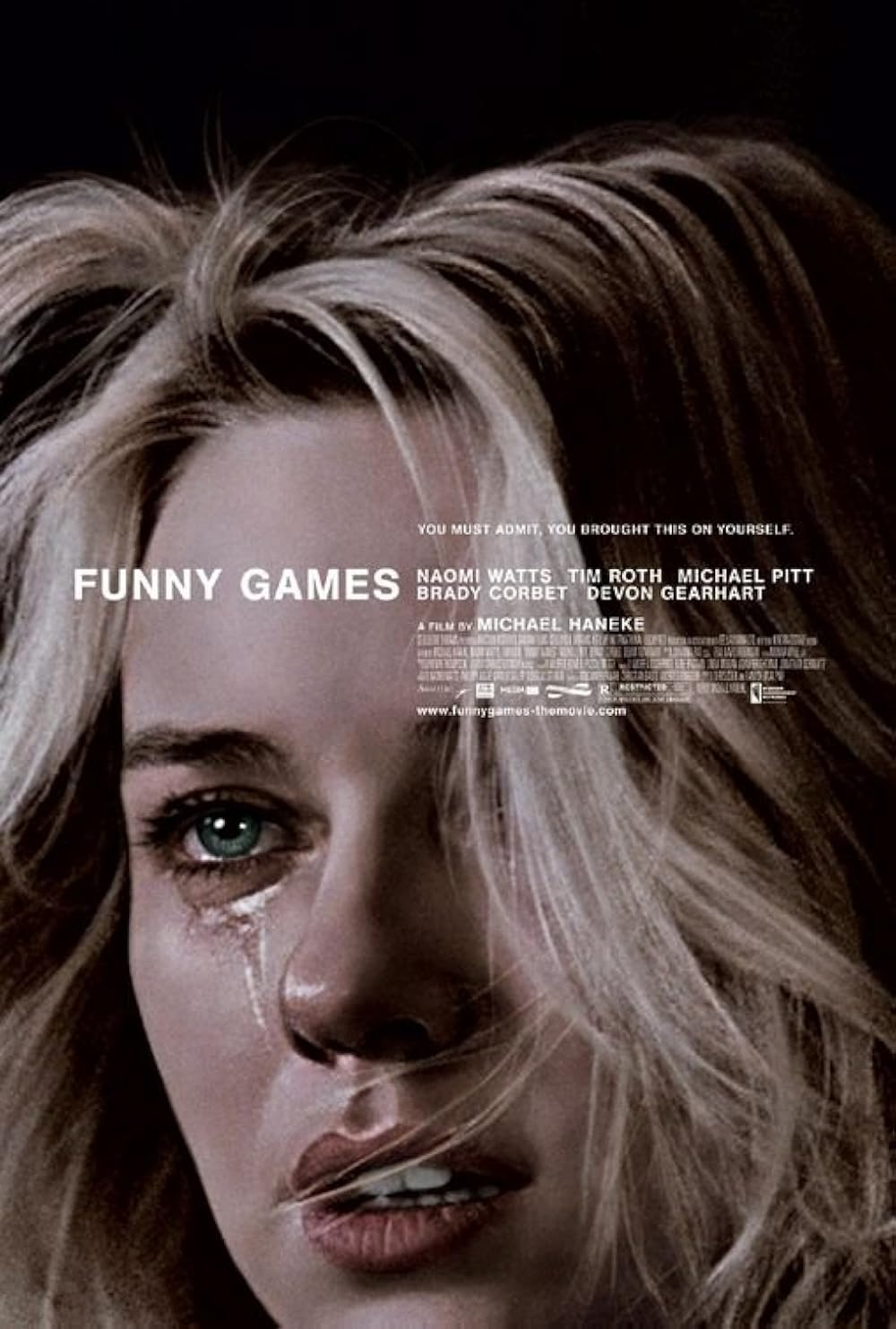

Funny Games

By Brian Eggert |

Michael Haneke’s film Funny Games, an English-language remake of his German language original of the same name, operates shot-by-shot the same as the first, simply more consumable for American audiences unwilling to read subtitles. And while I might not approve of remakes normally, American audiences will find Haneke’s argument salient, profoundly so, as we’re frequently overwhelmed by torture porn like Hostel, for which this picture is an antithesis.

Don’t think of Haneke’s picture as a thriller, bound by typical thriller tropes, complete with an exciting thriller climax and gratifying conclusion. Think of it as an experiment to show you how Hollywood cinema has manipulated your expectations by putting you through a gauntlet of terrible events intended to disturb you. But rather than involve himself in the types of films he seeks to discredit (Captivity, Saw, etc.), Haneke avoids depicting violence for entertainment purposes, explaining in a recent interview, “I don’t really want to be part of this violence pornography of the mass media.”

The film begins with a bourgeois family driving to their lakehouse, in a community where every driveway has a gate and every dock a sailboat. We learn virtually nothing about them, except that they’re happy and together whole. Unpacking and opening up the house to breathe, Ann, the wife, played with bravado devotion by Naomi Watts (also the film’s executive producer), hears a knock on the door. George, played by the underused and underappreciated Tim Roth, works outside, prepping their sailing boat with their son Georgie (Devon Gearhart, whose role is limited but well-acted). When Ann answers the door, she finds a yuppie twentysomething, Peter (Brady Corbet), clothed in a white polo shirt with white gloves and greasy hair, asking to borrow eggs. He’s later joined by Paul (Michael Pitt), whose description is identical to Peter’s.

Both men are polite, even eerily friendly, speaking in refined tongues about good manners and civility. But what follows is a series of twisted words and intentionally misinterpreted suggestions, with Paul and Peter soon holding the family captive, torturing them into providing amusement for, well, you, the viewer. After incapacitating George with a golf club to the knee, they propose a wager: that the family will not be alive after roughly twelve hours. To win, they carry out a series of humiliating and damaging acts, all highlighted by the wonderful performances of Watts and Roth. As to their intentions, we cannot say, since we’re never told.

In place of an explanation, Haneke winks at the camera, almost literally, when his white-clad antagonists break the Fourth Wall. Speaking directly to the audience, Paul asks what we want to see and our expectations. Sometimes, he gives us a knowing smile—as if saying, Are you pleased? Their actions seem motivated by what they believe the audience will enjoy, despite acknowledging that we’re on the family’s side. We, the audience, encourage them to continue because that’s how the film should play out. The film recognizes how audiences thrive on violence, and it seeks to make us guilty of such masochistic desires. If we weren’t watching, the family wouldn’t be tortured, so it’s our fault.

Taking over movie critic duties on www.rogerebert.com while Ebert recovers from another surgery, blogmaster Jim Emerson’s recent Funny Games review claims the film is geared toward torture-porn aficionados. Emerson says Haneke’s audience members are lab rat subjects forced to endure “negative stimuli [such as] filmed violence, as substitute for painful electrical jolts.” Emerson goes on to say that Haneke intends to incite reactions from the audience, so when we become disgusted by the experiment, we should reject its approach and leave the theater. And while Emerson remains half-right about Haneke testing us with the film’s content, he seems to have been watching a different movie, since Haneke avoids depicting violence—in truth, not one actual violent act is viewed.

Haneke’s camera always pulls away, careful not to glorify what today’s torture-porn subgenre gladly paints in bloody, focused detail. His violence and terror are implied with the camera often showing us the result of, or reaction to, the horrific events occurring off-camera, but never the physical act. There is, of course, one exception, which serves to better punctuate Haneke’s thesis: In one scene, Ann gets the upper hand and shoots Peter with a shotgun. Paul panics, searching for the television remote. Upon finding it, he hits rewind, reversing the film to before Ann took the gun; the second time around, Paul stops her, continuing with their experiment without any heroic interruption.

During my screening, the audience cheered when Peter’s body took the blast, flying against the wall in a bloody mess of liberating revenge. But Haneke’s film isn’t about living up to the audience’s standards and playing into Hollywood thriller archetypes, where after suffering much duress, the good guys eventually take down the bad guys. Instead, after rewinding the film’s events, violence becomes reality again, and not the safe and thrilling violence today’s cinema depends on.

While the movie could have easily delved into the scummy torture-porn arena, Haneke refuses to reduce himself to such lows. Instead of providing a diversion, he challenges us to think about movie violence, which, admittedly, will be a hard lesson for many viewers expecting a mainstream thriller. He outlines cinematic reality because movies are not necessarily everyday reality but a produced version of it we’ve become accustomed to. Growing used to cinematic reality, in turn, makes it real, blurring the lines between fantasy and reality. What an unfortunate truth to moviegoing. Indeed, Haneke’s Funny Games, through an emotionally exhausting and graphic satire, reemphasizes those lines and will have you questioning the modus operandi of future thrillers relying on violence as their means of entertainment.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review