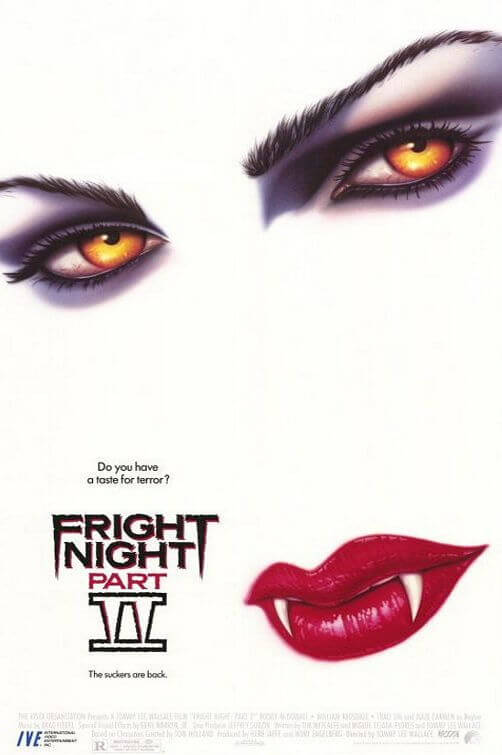

Fright Night Part 2

By Brian Eggert |

In the very 1980s way it explores the standard my-neighbor-is-a-vampire yarn, Tom Holland’s 1985 horror-comedy Fright Night has established a considerable following over the last thirty years, enough to warrant a respectable remake in 2011 and a pop-culture status that rises above unwarranted cult enthusiasm. The same cannot be said for its sequel, Fright Night Part 2, released in 1988 to indifferent reviews and poor box-office performance. In the years since its debut, the sequel has been virtually forgotten, unavailable on various home video formats, and rarely shown on cable television. And, no matter how much of a cult classic the original remains, it hasn’t resulted in a burning interest for the maligned sequel. Given this trend, after tracking down the film, one might expect to find a product worthy of its dismissal; but this is not the case. While it may not have all the charm or originality of Holland’s first entry, it’s a capably made sequel that contains some expected horror-sequel clichés and yet, in the end, stands as an entertaining and underrated follow-up.

Of course, Fright Night Part 2 contains plenty of moments plagued by sequelitis, where the filmmakers employ some Hollywood sequel-isms as an excuse to explore Holland’s likable characters once more. Holland, busy shooting Child’s Play (1988) with his Fright Night star Chris Sarandon, gave up director duties to Tommy Lee Wallace, a frequent collaborator with John Carpenter and helmer of the destined-to-fail-but-nonetheless-underrated Halloween III: Season of the Witch (1982). Wallace co-wrote the script with Tim Metcalfe and Miguel Tejada-Flores, and he delivers solid production values and excellent use of his widescreen frame. In a setup carbon-copied from the original, Part 2 has just enough details switched around to make it interesting. When the film opens, several years have passed since high-schooler Charlie Brewster (William Ragsdale) excised his neighborhood of a vampire threat alongside his idol, skeptical horror host Peter Vincent (Roddy McDowall). Now he’s in college and just finishing several years’ worth of therapy to convince himself there were no vampires—that a serial killer carried out the murders. Meanwhile, the sequel relies on a role-reversal between Brewster, now a non-believer, and Vincent’s vamp paranoia when he begins to suspect a tenant in his apartment complex has fangs.

To some extent, the lack of interest in the sequel is justified. In many ways, it’s more of the same. Here, a mulleted Charlie continues to abandon chances to improve relations with his sexually inhibited girlfriend, Alex (Traci Lind), to spy on suspected vampires. He’s grown out of his teenage horror aficionado phase and entered his sex-obsessed twenties. As a result, the reformed, non-believing Charlie is less interesting; instead of horror movie posters on his bedroom walls, his dorm room is covered with posters like Sex Kittens Go to College and Women’s Prison. And yet, his character’s signature sexual repression remains intact, despite the film’s prominent theme of coed sexuality. But his inner beast is unleashed when he sees the new arrival in Vincent’s building, the Frida Kahlo-looking “performance artist” Regine (Julie Carmen), who seduces Charlie and gradually turns him into a vampire. Alex and Vincent fight back and with them, eventually, Charlie. The plot itself works out in typical fashion with vampire explosions and oozing aplenty in the climactic battle.

Certainly, this isn’t the most coherent or tightly constructed of stories, but the material still has enough kitsch value and real-life parallels for horror aficionados to maintain interest. Consider how Peter Vincent is replaced in his hosting duties by Regine, and how this is not unlike how Elvira ultimately replaced the real-life “Fright Night” host Larry Vincent. Elsewhere, the film has some weird stuff going on. Regine’s oddball vampire entourage is notable for its creature confusion. There’s an African-American vamp named Belle whose androgynous appearance anticipates Dil from The Crying Game. What might be incessant questions about Belle’s gender are forgotten when he rollerskates down an empty hallway after an art student whose bloody death results in a Pollock-inspired canvas of red. Then there’s Louie (John Gries), a sort of wiseguy who’s after Alex, and who turns into a brown, hairy, werewolf-looking thing—except, curiously, he is a vampire according to the movie’s use of roses as vampire repellent (further confusion about this creature stems from the fact that, just a year before, Gries played a werewolf in Fred Dekker’s The Monster Squad). They’re all driven around by the frog-mouthed, bug-eating limo driver named Bozworth (Brian Thompson).

The weirdness continues as Charlie’s random friend Richie (Merritt Butrick, from Star Trek: The Wrath of Khan) appears out of nowhere and then disappears (he was no Evil Ed). Other story elements in Fright Night Part 2 make even less sense: There’s no police presence or investigation into the various teen deaths by a vampire on campus, nor a disbelieving cop to disregard it when Charlie claims it’s a vampire attack. Out of the blue, Charlie’s shrink Dr. Harrison (Ernie Sabella) reveals himself to be a bloodsucker in a plot detail quickly forgotten. The film also has an unusual preoccupation with bowling—including a sequence where Charlie bowls behind sunglasses, and later a vampire bowling montage featuring Regine’s entourage. (Apparently, there’s nothing else to do in this college town except bowl.) But no matter. The film brings enough genre suspense and ’80s-brand idiosyncrasy—not to mention its sheer peculiarity—to keep an audience rapt in both the entertainment value and the strange, humorously dated, and outright bizarro quality of it all.

Perhaps its narrow commercial appeal as a sequel to a cult favorite is why 1988 audiences barely had an opportunity to see Fright Night Part II. When it was released, critics and audiences responded with summary dismissal. Few critics bothered writing a review; among them, Variety offered modest praise in its assessment, calling the film a “better than the average shlocker.” Although a major studio, TriStar Pictures, had released the original film, the sequel was produced by The Vista Organization and distributed by the now-defunct label New Century Vista onto a mere 148 screens, where it earned a little under $3 million domestically (the original reached upward of 1,000 screens and made about $25 million). Home video offered limited options for potential fans, including a VHS and short-lived DVD release in pan-and-scan, which is no longer in print. Despite the popularity of cult horror on disc, no plans for a Blu-ray have been announced. An audience exists for the film, be they fans of Fright Night or simply horror aficionados. And on those terms, it’s a lark—not high art of even expert genre fun, but an entertaining guilty pleasure that deserved better than to be dismissed and forgotten.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review