Fright Night

By Brian Eggert |

Made in the heyday of horror movies, the 1985 hit Fright Night works so well because its writer-director Tom Holland approaches the material with nostalgia for the genre’s origins. Holland embraces cliché horror tropes intentionally and reinvigorates them into a real-life setting (real-life for the 1980s, that is). Released in the prime of the slasher movie craze, when Friday the 13th, Halloween, and A Nightmare on Elm Street were all franchises well into their sequels, Holland develops something different, something with a consciousness. With a concept that revolves around what happens when a horror-loving teenage boy suspects his new neighbor to be a vampire, the result fondly remembers a simpler time for the genre, and predates Scream’s self-referential style by more than a decade.

In the opening scene, horror movie aficionado Charley Brewster (William Ragsdale, of Herman’s Head fame) finally convinces his girlfriend, Amy (Amanda Bearse, later to become Marcy D’Arcy on TV’s Married with Children), to have sex after a year of waiting. But at that moment, Charley is distracted by something outside—he sees his new neighbors carrying a coffin into their basement cellar. Frustrated by Charley’s obliviousness to her readiness, Amy storms off, while Charley’s suspicions grow. The next day, he sees a female escort going into the neighbor’s house (perpetually shrouded in fog), and later, he hears screams. It’s not long before the news reports on a string of murders in Charley’s own Small Town, USA. All of his suspicions are confirmed when, playing peeping tom one night, he spies through his window the charismatic neighbor, Jerry Dandrige (Chris Sarandon), who reveals his fangs and kills another female victim. Except Jerry happens to look across the way to notice Charley spying.

As Charley attempts to convince his friends that his neighbor is a vampire, his doubting weirdo pal “Evil” Ed (Stephen Geoffreys) relates all the usual movie tricks with which Charley should protect himself: holy water, garlic, crucifixes, a stake through the heart, and never inviting a vampire inside your house. Of course, Charley’s busybody mother (Dorothy Fielding) invites Jerry over on her own, wanting to meet the handsome new neighbor. In their awkward social meeting, Jerry insinuates her invitation will allow him to come over whenever he wants (gulp). Desperate for help, Charley goes to the only person he trusts to kill a vampire: penniless late-night horror host Peter Vincent (Roddy McDowall, deliciously campy), whose program “Fright Night” was recently canceled. Vincent reluctantly agrees to help only after Charley’s concerned, still-unbelieving friends Amy and Ed offer him some quick cash. But as Vincent and Charley’s friends arrange a staged “vampire test” with Jerry to prove to Charley he’s not a vampire, Vincent becomes convinced Jerry is indeed a creature of the night.

As Charley attempts to convince his friends that his neighbor is a vampire, his doubting weirdo pal “Evil” Ed (Stephen Geoffreys) relates all the usual movie tricks with which Charley should protect himself: holy water, garlic, crucifixes, a stake through the heart, and never inviting a vampire inside your house. Of course, Charley’s busybody mother (Dorothy Fielding) invites Jerry over on her own, wanting to meet the handsome new neighbor. In their awkward social meeting, Jerry insinuates her invitation will allow him to come over whenever he wants (gulp). Desperate for help, Charley goes to the only person he trusts to kill a vampire: penniless late-night horror host Peter Vincent (Roddy McDowall, deliciously campy), whose program “Fright Night” was recently canceled. Vincent reluctantly agrees to help only after Charley’s concerned, still-unbelieving friends Amy and Ed offer him some quick cash. But as Vincent and Charley’s friends arrange a staged “vampire test” with Jerry to prove to Charley he’s not a vampire, Vincent becomes convinced Jerry is indeed a creature of the night.

Some typical ‘80s moments occur as the film moves forward, such as when Jerry, who suspects Vincent knows he’s a bloodsucker, goes after Charley and Amy, cornering them in a disco. Jerry hypnotizes Amy, who looks suspiciously like one of his former lovers from ages ago (a pseudo-classical painting reveals Jerry’s former sweetheart, hilariously complete with Amy’s pink ‘80s ribbon in her short, tomboy haircut). Electronic sex oozes from their seductive dance to Ian Hunter’s “Good Man in a Bad Time” and the suggestive lyrics of Evelyn ‘Champagne’ King’s “Give It Up,” while Jerry’s wide-neck sweater tells us even though he’s undead, he can still be hip.

Despite such moments of unavoidable ‘80s cheese, Holland’s film benefits from smart casting. Sarandon and his character’s invincible human lackey, Billy Cole (Jonathan Stark, sporting a fluffy coif), look as normal as can be. Both play with the fact they’re supernatural monsters to funny effect when Charley brings the police to question them. (NOTE: It’s never made clear who or what Billy Cole is. He’s not a vampire, given his non-reaction to sunlight. But he’s not merely Jerry’s human familiar either, since he rises after taking several bullets from Peter Vincent’s gun. So what is he?) Moreover, Geoffreys brings unsettling energy to his performance; his jarring laughter is even heightened after he’s turned into a vamp. The offscreen knowledge that Geoffreys later became a gay porn star brings an unintended sexual component and intangible peculiarity to his performance, as the actor salivates through his false vampire teeth and delivers lines as if unhinged from reality (“Oh, you’re so cooool Brewster!”)

However, more than anyone, McDowall’s doubter performance steals the show. His British thespian voice brings ironic class to his role, transforming into a bonafide vampire killer by the finale—just like the one he plays on TV (as Jerry quips, “It’s ‘Frrrrright Night… For real!”). The very notion of a horror telecast host like Peter Vincent recalls ‘80s icon Sinister Seymour, as played by actor Larry Vincent, who hosted a show called “Fright Night” that aired low-budget horror and sci-fi movies. When Vincent died, he was replaced by Elvira: Mistress of the Dark, and the show was renamed “Movie Macabre.” It’s a clever bit of plotting and a heartfelt nod on Holland’s part, not only to have a horror fanatic and devout believer confronted by a vampire, but to have a horror host, always surrounded by ghoulish images from Hollywood in his dank little apartment, play the skeptic. In terms of Holland’s character arcs, Vincent makes far greater a transformation than the comparatively uninteresting Charley Brewster.

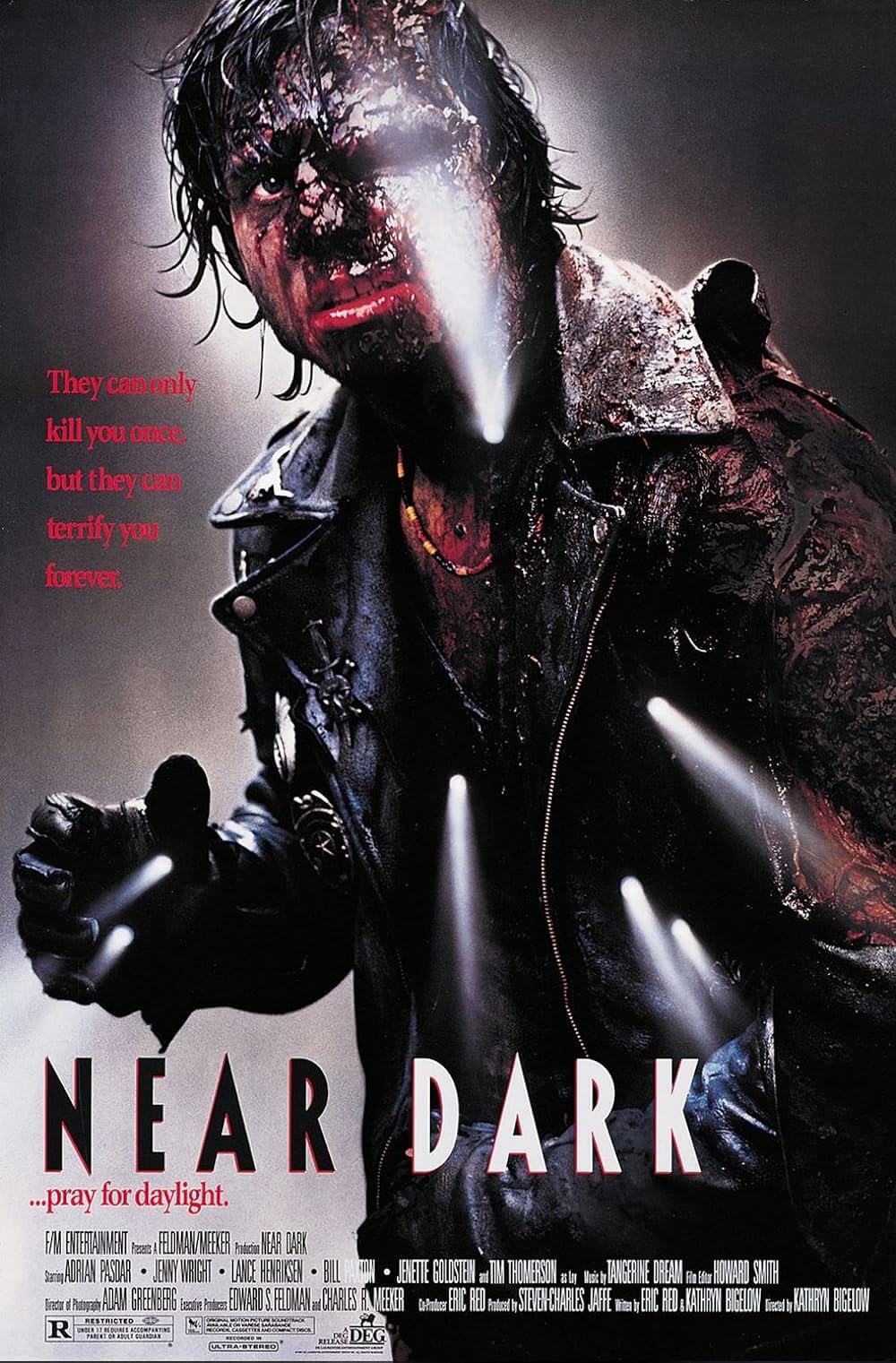

Holland’s blend of classic vampire yarns (represented by Peter Vincent) with modern sensibilities (represented by Charley Brewster) finds a unique intermingling in the film’s monster movie effects. Consider how Jerry turns into a bat and flies off, the wires on the rubber prop all but visible, while it’s been years since modern vampires have done anything so cartoonish. Holland embraces the most hackneyed vampire mythologies out of respect for the institution but innovates upon them with wry humor and fresh makeup designs. Jerry’s vampire form transforms from a swingin’ ‘80s player to a red-eyed, grotesque-faced creature heralding vamps from The Lost Boys and From Dusk Till Dawn. However, “Evil” Ed’s makeover is the film’s most disturbing visual, above all in his strangely dismaying stake-through-the-heart death scene where he degenerates from a wolf to man, all the while Peter Vincent watches with horrified, amazed, and saddened eyes (a great piece of acting by McDowall).

Holland’s blend of classic vampire yarns (represented by Peter Vincent) with modern sensibilities (represented by Charley Brewster) finds a unique intermingling in the film’s monster movie effects. Consider how Jerry turns into a bat and flies off, the wires on the rubber prop all but visible, while it’s been years since modern vampires have done anything so cartoonish. Holland embraces the most hackneyed vampire mythologies out of respect for the institution but innovates upon them with wry humor and fresh makeup designs. Jerry’s vampire form transforms from a swingin’ ‘80s player to a red-eyed, grotesque-faced creature heralding vamps from The Lost Boys and From Dusk Till Dawn. However, “Evil” Ed’s makeover is the film’s most disturbing visual, above all in his strangely dismaying stake-through-the-heart death scene where he degenerates from a wolf to man, all the while Peter Vincent watches with horrified, amazed, and saddened eyes (a great piece of acting by McDowall).

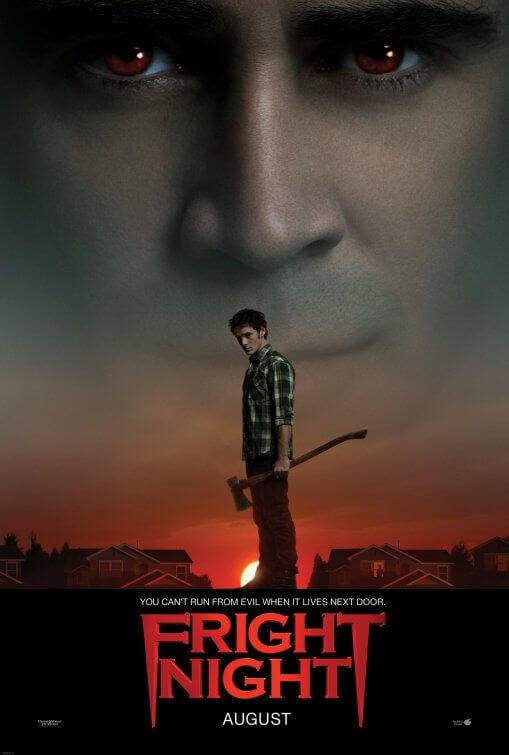

Along with filmmakers akin to John Landis, Joe Dante, and Fred Dekker, Holland, who would go on to make Child’s Play and Thinner, belongs on a shortlist of directors from the ‘70s and ‘80s whose genre know-how shaped horror-comedy into joyous postmodernism. Fight Night earns its place alongside An American Werewolf in London, Piranha, and Night of the Creeps as one of the funniest, smartest, and most entertaining efforts in the period’s innovative horror-comedy heights, one whose influences are still felt today in titles ranging from Tremors to Scream to Shaun of the Dead. And with the 2011 remake Fright Night starring Anton Yelchin and Colin Farrell, the film’s influence has reached beyond your average ‘80s horror cult fare into something far more memorable than dime-a-dozen slasher movies or mindlessly gory schlock, and altogether worthy of celebrating.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review