Freud’s Last Session

By Brian Eggert |

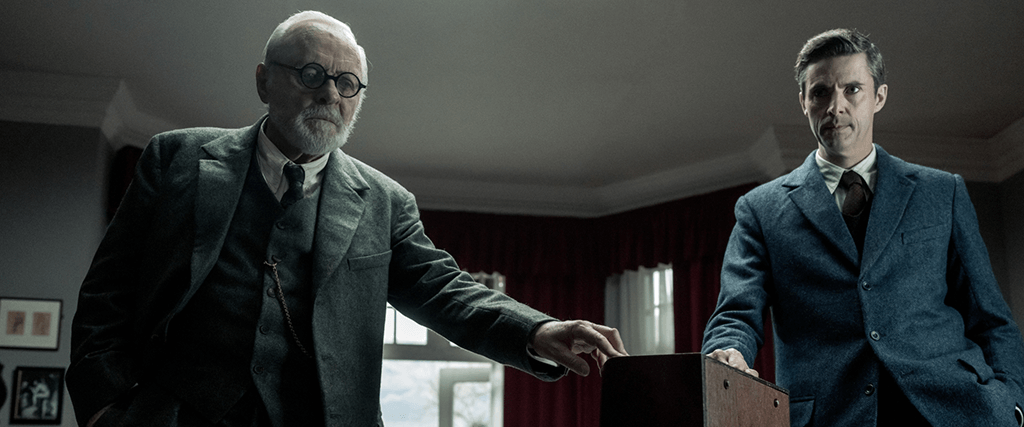

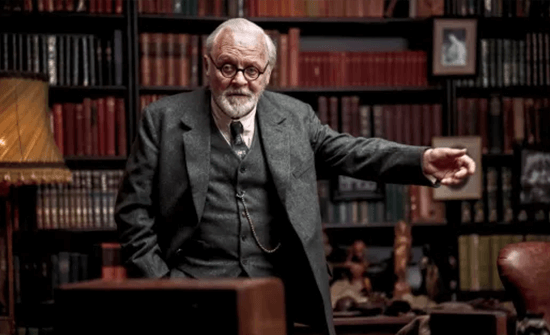

Freud’s Last Session imagines a meeting between devout atheist Sigmund Freud, who wrote the first books on psychoanalysis, and Christian apologist C.S. Lewis, who penned the Chronicles of Narnia books. Set in September 1939, a couple of days after Germany invaded Poland and a few days before Freud’s death, this work of speculative fiction attempts to answer the question of which unidentified Oxford scholar the Austrian neurologist actually met with around this time. The screenplay, co-written by director Matthew Brown and playwright Mark St. Germain, draws from the latter’s 2009 play, an adaptation of Armand Nicholi’s 2002 book, The Question of God. The setup places two men of opposing ideals on religion in a room, explores their identities and worldviews, and allows them to hash out their differences through a lofty debate. If the material often feels forced, at least the production boasts two fine performances from Anthony Hopkins as Freud and Matthew Goode as Lewis.

The impetus for this tête-à-tête is shaky, as is much of the dramaturgy established around it. At this time, Freud had left his home in Vienna, having delayed his flight from the Nazis for the relative safety of London. Born to Ashkenazi Jewish parents, Freud couldn’t grasp the reality of the Nazi threat and initially didn’t believe they would rise to power until they did. The Nazis, meanwhile, targeted his “Jewish science” of psychoanalysis. The opening shots survey Freud’s office, filled with small sculptures and books, while a British radio broadcast underscores the Nazi threat with their speeches calling for the eradication of Jews in Europe. Outside, the British authorities evacuate children to the countryside in case of bombings. But for some reason, even with the world falling apart around him, Freud requests a meeting with Lewis to discuss various topics from past traumas to fantasy fiction to religion. Lewis shows up on the defensive, which is understandable, given that Freud has argued religion is an imbecile’s belief and an “obsessional neurosis.”

Given the start of another world war and the impending end of his own life, Freud has mortality and its meaning on the brain. He can’t see the rationale of war as another of “God’s mysterious ways.” Lewis doesn’t offer much by way of convincing rebuttals about Christianity, except to note that Jesus was a real man, not a myth. Most myths, such as the Greek or Roman gods, have no basis in reality. He also dwells on moments when Freud uses “God” in expressions such as “My God,” suggesting that there might be some buried faith in Freud yet, as though linguistic expressions serve as proof of anything. But Freud treats the notion of an all-powerful deity with aching incredulity over the losses he has experienced; he seems to laugh and cry at the meaningless cruelty placed upon his daughter and grandchild, who died too young. If only humanity would “grow up” and stop believing in such nonsense, perhaps they could make some meaningful progress.

Brown and St. Germain’s screenplay pads the stage’s two-hander with flashbacks and subplots that prove more distracting than insightful. Lewis’ childhood and traumatic service in the First World War receive some consideration, charting the origin of his affinity and need for fairy tales and fantasy, and his scholarly reconsideration of Christianity as more than myth. Freud’s childhood also receives some cursory scenes, although they remain unshared with Lewis and exclusive to the viewer. Elsewhere, Freud’s daughter, Anna (Liv Lisa Fries), who specializes in child psychoanalysis, remains unquestionably devoted to her father, unable to tell him no when he calls during her lectures, demanding that she and no one else secure his medicine. He has mouth cancer that leaves him in pain, desperate for morphine, and weighing whether to end his own life.

Brown and St. Germain’s screenplay pads the stage’s two-hander with flashbacks and subplots that prove more distracting than insightful. Lewis’ childhood and traumatic service in the First World War receive some consideration, charting the origin of his affinity and need for fairy tales and fantasy, and his scholarly reconsideration of Christianity as more than myth. Freud’s childhood also receives some cursory scenes, although they remain unshared with Lewis and exclusive to the viewer. Elsewhere, Freud’s daughter, Anna (Liv Lisa Fries), who specializes in child psychoanalysis, remains unquestionably devoted to her father, unable to tell him no when he calls during her lectures, demanding that she and no one else secure his medicine. He has mouth cancer that leaves him in pain, desperate for morphine, and weighing whether to end his own life.

Hopkins and Goode breathe life into the chatty material, making its many asides feel like unnecessary distractions from the engaging debate at the center. Hopkins has the showier and more complicated role, grappling with death and a lifetime of memories that prompt him to fade away in mid-conversation—not unlike his Oscar-winning role in 2021’s The Father. Goode’s sturdy screen presence doesn’t make Lewis much more interesting as a character. Even after momentary doubts, Lewis’ certainty remains dull and two-dimensional next to his intellectual sparring partner. Cinematographer Ben Smithard delivers their conversation in capably textured images, supported by Luciana Arrighi’s stately production design and Eimer Ní Mhaoldomhnaigh’s costumes. A few visual flourishes break the predictable period piece milieu, such as an impressive scene inside Lewis’ head in which a diorama comes to life, leading to a not-so-impressive CGI deer. But in most technical areas, the film is effective.

If the middle section meanders and bloats the 108-minute runtime, Brown at least ends Freud’s Last Session on a thoughtful and ambiguous note. “One of us is the fool,” Freud remarks. “If you’re right, you won’t be able to tell me so. And if I’m right, no one will ever know.” After saying goodbye, Lewis is left with lingering uncertainties and dreams of wandering alone in the dark woods, only to be greeted by a reassuring light. Freud sits, contemplating death and the uncomforting nature of his beliefs in the face of his mortality. The answer, the movie supposes, isn’t a final destination; it’s a journey to discover what you believe. Other films have taken a similar approach to this subject matter more successfully—Ang Lee’s Life of Pi (2012) comes to mind. Freud’s Last Session barely tackles its two main characters with sufficient depth. What chance does it have of adequately confronting eternal questions about faith and death?

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review