Free State of Jones

By Brian Eggert |

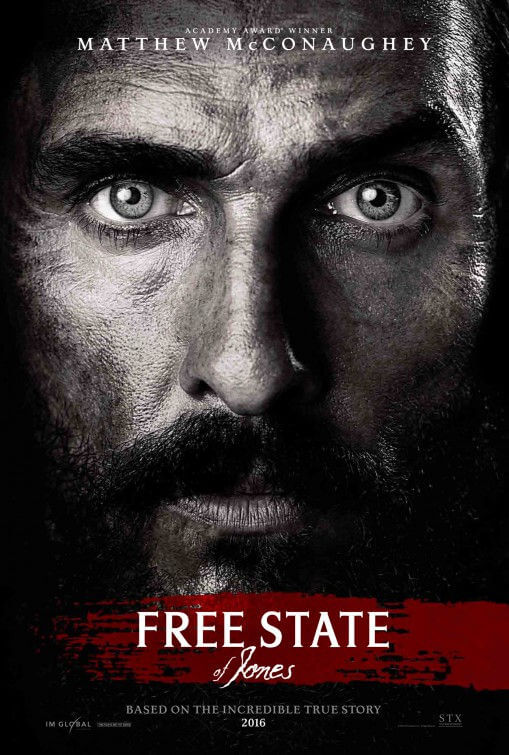

A potentially sprawling historical drama is beset by an unfocused screenplay in Free State of Jones, the controversial true story of Newton Knight, a Confederate deserter who led a small band of renegades against Southern rule during the Civil War. Southerners still consider Knight one of their history’s great criminals, whereas the North views him as an early civil rights freedom fighter. Writer-director Gary Ross takes what might have been a significant, thrilling account of a forgotten chapter in American history and turns it into a didactic lesson, like a dramatically reenacted documentary. Real Civil War photographs appear onscreen as transitional devices, whereas titles explain the time and place after one of the film’s many leaps forward to advance the story, leaving the emotional draw inert. Ross keeps his audience at a distance for most of the picture with such storytelling mechanisms, never really delving into Knight as an individual—just his significance as an historical figurehead.

In a role that recalls Matthew Broderick in Glory (1989), Kevin Costner in Dances with Wolves (1990), and Tom Cruise in The Last Samurai (2003), Matthew McConaughey stars as Knight, a white man fighting for equal rights. It’s a performance that sends the McConaissance into a valley, despite the actor’s committed presence behind his gaunt physique, intense eyes, and scraggly beard. When the film opens in 1862, Knight serves as a Confederate nurse who rushes wounded soldiers from the battlefield. He retreats from battle after a neighbor boy dies and vows to give him a proper burial. Once back home, Knight witnesses Confederate soldiers loot struggling farmers for food and clothing to support the war effort, and he resolves to stand up to them. Knight becomes a wanted man after his initial encounter with the rebellion’s taxation collectors, sending him into the Mississippi bayou to find asylum among a handful of fleeing slaves. There, Knight befriends Moses (Mahershala Ali) and, having been a blacksmith, helps release Moses from his spiked iron collar. And though the libertarian Knight seems determined to fight back against Confederate soldiers, he aligns with fewer African Americans than one might expect based on this setup.

Amassing a ragtag army of distressed locals, Knight organizes and strikes back against the Southern rebellion, though his army largely consists of white farmers. More concerned with socioeconomic hierarchies than race, the film explores modern-day parallels and, in a way, hopes to rabble rouse. Not that the comparisons aren’t sound, or valid, because they are. For example, Knight points out the hypocrisy of a law in which Confederate soldiers are exempt from combat if they own 40 or more slaves. The law, designed to protect wealthy cotton farmers and slavers from having to enter battle, reminds Knight that he’s fighting a rich man’s war. Replace Southern cotton with Iraqi oil, and now you have yourself an effective historical parallel. Unfortunately, the trajectory of this theme in Free State of Jones considers the issues of racism and the dehumanization of African Americans as symptoms of the perceived greater problem of social inequality.

Ross’ script takes some curious, somewhat troublesome turns to explore this issue. After soapboxing for the first half of the film about social inequality, Knight finally makes an apt comparison between poor white folk and slaves—since they’re both at the mercy of the one-percentile. During a scene in which one of Knight’s followers calls Moses the N-word, Knight asks the man, “How you ain’t a nigger?” Meaning, since meager white farmers answer to rich men the same way Black slaves do, how are they different? Aside from the atrocious punishments, unending rape, and complete lack of physical or spiritual freedom for African Americans, Knight may have a point. However, Ross’ script feels overly concerned with exploring matters of social inequality, and he doesn’t spend enough time acknowledging the key manifestations of the widespread socioeconomic imbalance: slavery and rampant racism.

That’s not for lack of trying, of course. Free State of Jones contains a lot of scenes that could have been handled differently to achieve a more effective commentary on America’s history of racism. Interjected between moments in the 1860s are brief courtroom scenes set 85 years later. On trial in the 1950s is Knight’s descendant, Davis (Brian Lee Franklin), who’s been arrested in Mississippi for marrying a white woman. As we discover, Newton Knight had a white wife, Serena (Keri Russell), who abandoned him during the war, and they had one son; he later took a common law wife in a freedwoman, Rachel (Gugu Mbatha-Raw), and they had a son as well. (In reality, Knight had fourteen children between Serena and Rachel.) The off-putting, incongruous scenes with Davis serve to illustrate that racism and inequality still exist in Mississippi, which wasn’t really news to anyone.

Although Ross’ formal package is top-notch—complete with earthy lensing by Benoît Delhomme and an eye for historical details in the costumes and sets—and the story proves informative at times, Free State of Jones slogs because of its episodic, edifying approach. No matter what’s happening in the story, Ross finds a way to formally detach his audience from the drama to a frustrating degree. One exception involves a scene later on, after the Emancipation Proclamation was signed, when Moses’ son is captured by former slavers and placed into an “apprenticeship”—just one of the many ways in which the South attempted to keep things the same after the change. The sequence captures the ugliness of an abominable historical truth, as well as the emotional height when Knight joins Moses to retrieve the boy back from his captor. It’s also one of the few scenes in Free State of Jones that works on multiple levels, from engaging drama to historically informative. This single sequence has enough drama for an entire film, but it’s only about five minutes of a two-hour-and-nineteen-minute picture. Ultimately, it just leaves us wishing the rest of the film had been so engaging.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review