Reader's Choice

Force of Evil

By Brian Eggert |

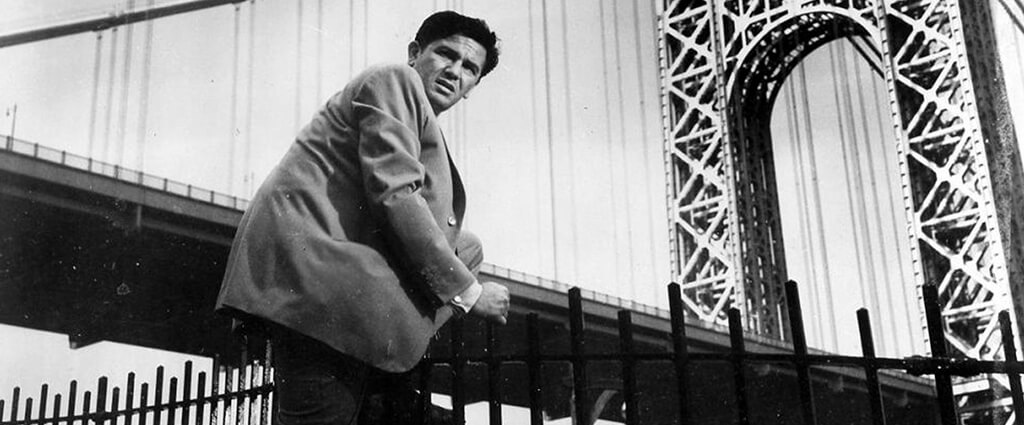

Force of Evil opens on a shot of Wall Street, the frame almost twenty stories high in the asphalt jungle. Below, a crowd full of wannabe movers and shakers bustles, and each one of them is desperate to make their fortune. Among them is Joe Morse (John Garfield), a successful attorney who, in his voiceover, schemes to make his “first million.” But this 1948 film noir has other things in store for Joe; he starts out with an office “in the clouds,” and he ends up at the lowest point imaginable. At first glance, Force of Evil might seem to be a standard noir programmer of the classic Hollywood postwar era, built up around the illegal numbers racket. Except, with his screenplay and direction, Abraham Polonsky takes an unflinching jab at America’s all-consuming capitalism, powerfully links the film’s themes with its noirish visual treatment and cutting, and uses poetic dialogue that has the gravitas of a Greek tragedy. Anchored by a razor-sharp yet sensitive performance from Garfield, Polonsky’s film is the legacy of two talents whose careers would be derailed by the House Un-American Activities Committee. Although it marks their only collaboration as actor and director, their production weighs ambition against morality in a streetwise yet socially conscious manner. It’s a hard-boiled and edgy film, but also a soul-searching view of American greed.

Although MGM distributed Force of Evil, Garfield’s independent production company, The Enterprise Studio, made the picture. Garfield founded the company after his contract with Warner Bros. expired, and he set out to produce projects on his own terms—joining the ranks of James Cagney, Humphrey Bogart, Olivia de Havilland, Ida Lupino, and other actors who wanted freedom from the major studios. Unlike some of his contemporaries, Garfield’s company started with a bang. Enterprise’s first production, Body and Soul (1947), featured Garfield as a boxer who tries to preserve his integrity when tempted by a crooked boxing promoter. Among the film’s many Oscar nominations, Garfield earned recognition for his leading performance, and Abraham Polonsky was nominated for his script. Garfield then hired Polonsky to make his directorial debut on the second Enterprise picture, Force of Evil, and again, the threat of selling out became a major plot point and existential theme. Coming from Garfield and Polonsky, the former a liberal activist and the latter a staunch Marxist, the film equates street-level racketeers and Wall Street dealmakers with criminals—or at least morally bankrupt.

Polonsky based his screenplay on Ira Wolfert’s 1934 novel Tucker’s People, a fictionalized account of the numbers racket in New York City before the state-controlled lottery took over. Garfield worked closely with Polonsky to reframe the book’s exposé-style account into a thriller. The screen story follows a thriving attorney who begins to question his commitment to making money at any cost. Early on, Joe helps a local crime lord manage the numbers, but he’s a man alone, driven by his greed in an unforgiving city—and Polonsky evokes this with several shots showing Joe isolated in the urban environment, inspired by the paintings of Edward Hopper (see Nighthawks, 1942). Expressionistic flourishes aside, the film boasts plenty of insight about “policy banks” and the 20 million suckers across America who gave their spare change to them at the time. Joe’s persistent narration throughout explains that everyday people would rather gamble by playing the numbers than pay their insurance policies, hence the name. And the term “banks” doesn’t mean a place where one can make withdrawals; rather, clandestine locations around the city that manage their territories, collecting bets and paying out when a number lands. But whether they’re small-time criminals or Wall Street fatcats, everyone’s in a racket.

Joe’s client and the numbers racket boss, Ben Tucker (Roy Roberts), has made gambling “legal, respectable, and very profitable”—at least on the face of it. The numbers are a scam, of course, as evidenced by Tucker’s plan for a hostile takeover that will combine the smaller policy banks into a single entity, which he intends to oversee. Joe helps him organize a scheme whereby every policy bank will be forced to sell to Tucker after a popular number—776, in honor of the impending July Fourth holiday—creates too many winners to pay. Joe’s estranged brother Leo (Thomas Gomez) runs one such bank, and Joe attempts to arrange for Leo to take advantage of the cheat, earn a hefty payday, and transition to Wall Street. But Leo’s sense of responsibility to those who placed bets at his bank, along with his general belief that Joe is shifty, prompt him to refuse Joe’s offer, which he deems “Blackmail!” As Joe tries to corner his brother into accepting the deal, he courts Leo’s assistant, Doris (Marie Windsor), whose innocence and eventual judgment of Joe’s shady lifestyle compel him into self-reflection. Moreover, Tucker’s ruthless takeover forces the bank’s employees to remain on the job against their will, which draws the attention of authorities and competing gangsters, who respond with respective raids and strong-arming. By the end, Leo puts a target on himself with his refusal to acquiesce to his brother’s plan; he ends up dead, and Joe is left tortured by his moral awakening.

Joe’s client and the numbers racket boss, Ben Tucker (Roy Roberts), has made gambling “legal, respectable, and very profitable”—at least on the face of it. The numbers are a scam, of course, as evidenced by Tucker’s plan for a hostile takeover that will combine the smaller policy banks into a single entity, which he intends to oversee. Joe helps him organize a scheme whereby every policy bank will be forced to sell to Tucker after a popular number—776, in honor of the impending July Fourth holiday—creates too many winners to pay. Joe’s estranged brother Leo (Thomas Gomez) runs one such bank, and Joe attempts to arrange for Leo to take advantage of the cheat, earn a hefty payday, and transition to Wall Street. But Leo’s sense of responsibility to those who placed bets at his bank, along with his general belief that Joe is shifty, prompt him to refuse Joe’s offer, which he deems “Blackmail!” As Joe tries to corner his brother into accepting the deal, he courts Leo’s assistant, Doris (Marie Windsor), whose innocence and eventual judgment of Joe’s shady lifestyle compel him into self-reflection. Moreover, Tucker’s ruthless takeover forces the bank’s employees to remain on the job against their will, which draws the attention of authorities and competing gangsters, who respond with respective raids and strong-arming. By the end, Leo puts a target on himself with his refusal to acquiesce to his brother’s plan; he ends up dead, and Joe is left tortured by his moral awakening.

All the while, Polonsky’s script pours out ornamented dialogue written in a tradition that was meant to be heard and appreciated. Polonsky writes with what critic William Pechtner calls “the sound of city speech, with its special repetitions and elisions, cadence and inflection, inarticulateness and crypto-poetry.” Many film noirs boast flavorful and punchy dialogue, but Force of Evil takes the amoral scenario and turns it into a thing of beauty through its words. When Joe eventually realizes the extent of what he’s done after weighing himself next to Doris’ purity, he offers a speech that finds him grappling with his brother’s cold rejection: “To go to great expense for something you want, that’s natural. To reach out to take it, that’s human, that’s natural. But to get your pleasure from not taking, from cheating yourself deliberately like my brother did today, from not getting, from not taking. Don’t you see what a black thing that is for a man to do?” But he goes on to consider Leo’s shame, while hinting at his own, and, in effect, considers his corruption: “How it is to hate yourself and your brother, make him feel that he’s guilty, that, that I’m guilty?” Polonsky’s sense of morality and judgment of his characters is unwavering, situating the conflict amid biblical allusions—specifically a Cain and Abel conflict between Joe and Leo—and in terms of good and evil extremes.

Polonsky’s visual treatment in Force of Evil adopts noir’s use of expressionistic light and shadow to reflect the film’s stakes. Veteran cinematographer George Barnes, no stranger to evocative imagery after lensing Rebecca (1940) and Spellbound (1945) for Alfred Hitchcock, shoots both on sets and in New York locations. Polonsky follows a trend in film noir pictures at the time that stopped using rear-projected scenes and replaced them with on-location city photography to give the viewer a sense of reality (see The Naked City, 1948). The scenes around Wall Street, often shot from lower angles to show Joe under the enormous pressure of their vast, corrupting forces, make Polonsky’s view of the rackets, legal or otherwise, unmistakable. However, the production’s sets allowed Barnes to create his most heightened uses of shadow. Early scenes appear straightforward and evenly lit, but as Joe gradually sees his own moral bankruptcy, more and more shadows emerge, as if consuming him. Finally, the climactic sequence featuring Joe, Tucker, and another top gangster shooting at each other in the dark turns into a black comment on their morality. The final scenes, where Joe races to locate his brother’s discarded corpse on the rocks near the Hudson River, with Doris trailing behind, makes excellent use of landmarks to capture Joe’s literal and figurative descent. “I just kept going down and down,” he tells us. “It felt like I was going down to the bottom of the world, to find my brother.”

Polonsky’s critique of greedy institutions and the people who purvey them is a singular achievement, in part because Force of Evil would be his first and last credit as a film director until 1969’s Tell Them Willie Boy Is Here. Before World War II, Polonsky was a card-carrying member of the Communist Party and a writer in left-wing newspapers. During the war, he served in the OSS and helped the French Resistance develop communications to help the war effort and maintain morale. Despite his service, he was among the many Hollywood talents called to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1951. Polonsky refused to comply with HUAC, and he was blacklisted. His work went uncredited on many screenplays until the late 1960s. Garfield’s career also met a premature end. He appeared before HUAC and, like Polonsky, refused to name names. The stress of HUAC’s reported investigation into his testimony, in conjunction with his high-intensity lifestyle and persistent heart problems after catching scarlet fever as a child, caused Garfield to die of a heart attack at 39. Watching Force of Evil, film enthusiasts ache over the loss of these two talents from the classical Hollywood scene and what they might have achieved together had they made even one more film.

Polonsky’s critique of greedy institutions and the people who purvey them is a singular achievement, in part because Force of Evil would be his first and last credit as a film director until 1969’s Tell Them Willie Boy Is Here. Before World War II, Polonsky was a card-carrying member of the Communist Party and a writer in left-wing newspapers. During the war, he served in the OSS and helped the French Resistance develop communications to help the war effort and maintain morale. Despite his service, he was among the many Hollywood talents called to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1951. Polonsky refused to comply with HUAC, and he was blacklisted. His work went uncredited on many screenplays until the late 1960s. Garfield’s career also met a premature end. He appeared before HUAC and, like Polonsky, refused to name names. The stress of HUAC’s reported investigation into his testimony, in conjunction with his high-intensity lifestyle and persistent heart problems after catching scarlet fever as a child, caused Garfield to die of a heart attack at 39. Watching Force of Evil, film enthusiasts ache over the loss of these two talents from the classical Hollywood scene and what they might have achieved together had they made even one more film.

Once Force of Evil opened on Christmas Day, 1948, it barely earned enough at the box office to keep Enterprise in business a short while longer, nor did the film receive overwhelming praise from critics. Variety remarked that it “fails to develop the excitement hinted at in the title,” but Bosley Crowther’s review for The New York Times declared it “brilliantly and broadly realized.” Enterprise distributed only one more picture, Caught, another film noir, this one directed by Max Ophüls in 1959 and starring James Mason, Barbara Bel Geddes, and Robert Ryan. Like most independent production companies of this era, the business folded under financial pressures and, combined with HUAC’s witchhunt, Garfield had no choice but to work as a free agent. After Force of Evil, he appeared in only a handful of other titles for Columbia, Warner Bros., and United Artists before his death. However, subsequent film noir enthusiasts recognized the punch Force of Evil delivers, including Andrew Sarris, who showered the film with praise in his book The American Cinema: Directors and Directions. Eddie Muller, host of “Noir Alley” on Turner Classic Movies, called it “one of the most distinctive and provocative crime pictures ever made in America.” And in his book Somewhere in the Night, Nicholas Christopher wrote, “The film is one of the fiercest dissections of laissez faire capitalism ever to come out of Hollywood.”

Such hyperbolic sentiments are warranted. Garfield and Polonsky get to the core of how capitalism corrupts, and it does not discriminate between blue-collar tenements and white-collar high-rises. Polonsky sought to portray how rampant greed and criminality spring from a system where money has more importance than morality, and large businesses buy out smaller ones through endless mergers and acquisitions—a commentary that feels ever more pertinent in today’s climate of rampant corporatization. Despite the power of its message, Force of Nature resists becoming preachy or political. Its taut, 79-minute runtime is laser-focused on Garfield, whose edgy and soulful performance conveys his character’s ruthless ambition and full recognition of how low Joe has sunk. Gomez is also terrific in Leo’s impassioned refusal to budge, as well as in scenes leading up to Leo’s demise. With his film, Polonsky sought to expose a bitter reality behind minor moral corruptions that, before you know it, drag you down to the bottom. In the last moments, Joe reflects, “If a man can live so long, and have his whole life come out like rubbish, then something was horribly wrong—and I decided to help.” Finally, Polonsky turns Force of Evil into more than another atmospheric crime story but a plea to acknowledge the moral compromises capitalism invites, and to help others recognize them.

(Note: This review was originally suggested on and posted to Patreon on September 14, 2022. Thank you, Julian, for selecting this film and for your continued support!)

Bibliography:

Bordwell, David, et al. The Classical Hollywood Cinema. New York: Columbia University Press, 1985.

Christopher, Nicholas. Somewhere in the Night: Film Noir and the American City. The Free Press, 1997.

Jewell, Richard B. The Golden Age of Cinema: Hollywood 1925-1945. Blackwell Publishing, 2007.

Pechter, William. “Abraham Polonsky and ‘Force of Evil.’” Film Quarterly, vol. 15, no. 3, 1962, pp. 47–54. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1210628. Accessed 3 September 2022.

Sarris, Andrew. The American Cinema: Directors and Directions, 1929-1968. E.P. Dutton & Co., 1968.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review