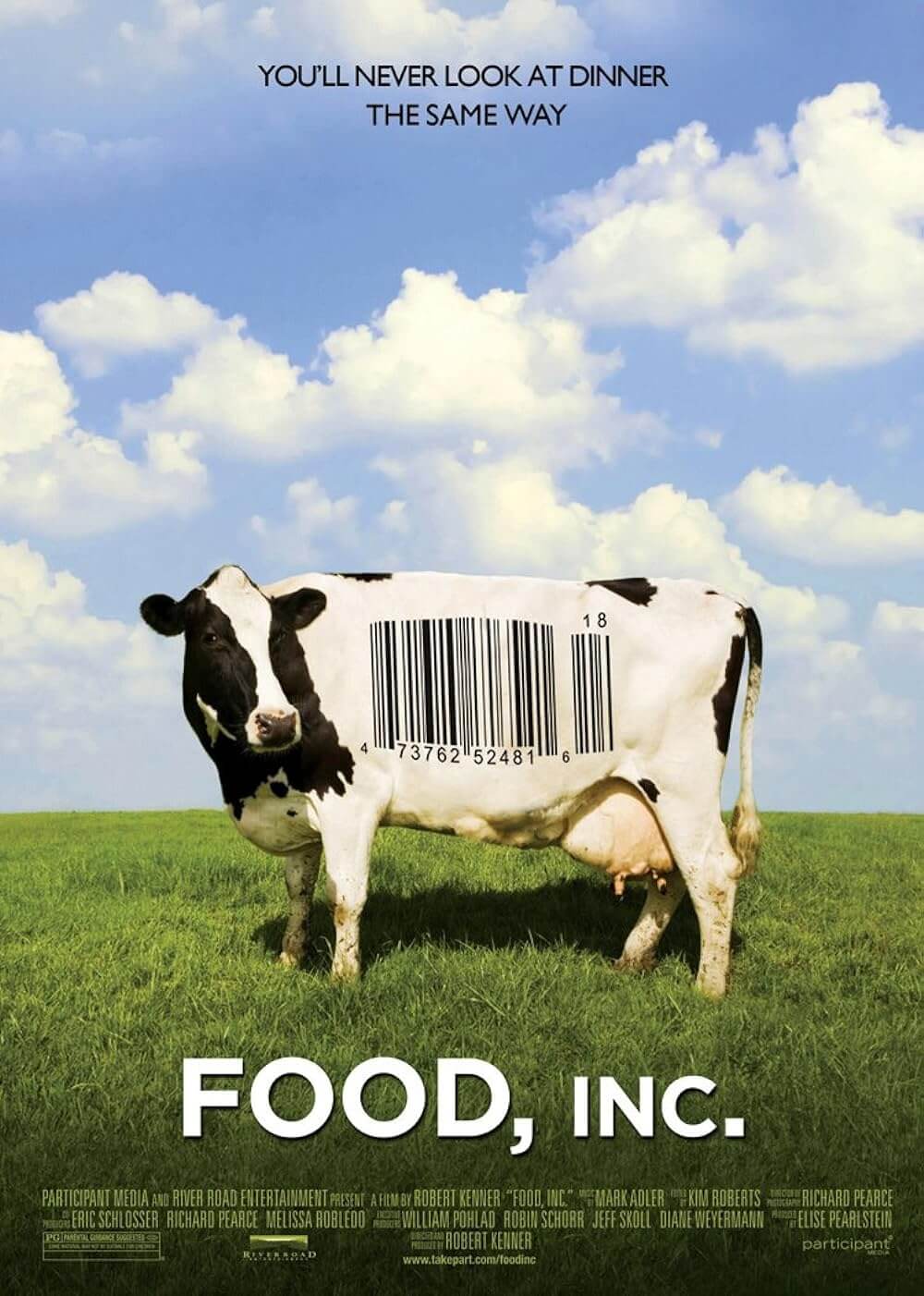

Food, Inc.

By Brian Eggert |

Food, Inc. argues that the American food industry needs a change. To inspire one, the film presents a horror show of appalling treatment of animals, compounded with staggering scientific and industry facts. The filmmakers present these truths in logical, unadulterated terms, using pictures and interviews to strengthen their position. This is such a successful documentary that this review doesn’t so much examine the way the information is presented but overviews the information itself so that you, the reader, might seek this film out and help support a desperately needed change.

Of course, the multinational corporations discussed therein all declined to be interviewed for the film. They also refused access to their processing plants, though covert cameras were used to capture some terrible, stomach-churning footage. Despite Tyson’s best efforts to convince poultry farmers to boycott the filmmakers, one farmer took a risk: We see her farmhouse where chickens packed to the brim cannot stand because their bodies have been engineered to grow faster than their legs can support them. “We’re not producing chickens,” a company man comments, “we’re producing food.” The documentary suggests that such detached thinking spreads like an infection to all forms of government, which, as always, supports corporations. Wasn’t it Kissinger who said, “We have no friends, America only has interests”?

The filmmakers are careful to avoid constructing an outright attack on the mega-conglomerates that control food distribution in America. Narrators and interviewees Eric Schlosser (author of Fast Food Nation) and Michael Pollan (author of The Omnivore’s Dilemma) lend the film striking authority, as they hope merely to inform consumers as to what they’re buying. They offer concerned criticism through facts by exposing these corporations’ processes—“A world deliberately hidden from us.” For example, did you know that if the USDA finds contamination in a meat processing plant, be it just once or a hundred times over, it doesn’t have the right to shut that plant down? The meat corporations egregiously won a court victory that gives the USDA basically no power.

Enter one of the country’s major slaughterhouses and you’re surrounded by a mist of blood, bile, and bacteria. Laborers—former farmers from Mexico put out of business by American corporations and imported into our country illegally by those same corporations for cheap labor—endure one of the most dangerous jobs there is for barely minimum wage. A few clean facilities cut their meat with ammonia to lessen the presence of bacteria in their product; now seventy percent of all hamburger is infused with this ammonia-meat product to prevent bacterial outbreaks. By using chemicals like ammonia, they’re trying to stop a lethal strain of E. coli, namely 157H7, which evolved in the stomachs of cattle when these companies started feeding them corn. Rather than eliminate the bacteria by feeding the cows what they’re supposed to eat, namely grass, they’d prefer to kill the bacteria with dangerous chemicals. Now the meat is “safer,” but sewage from these farms runs off and contaminates lettuce and spinach fields. A few decades ago, you never heard about E. coli, and now it’s everywhere because we made it.

These companies, we learn, have based the entire American diet on corn, because corn is cheap and plentiful. Around thirty percent of land in the United States is cornfields. Something like ninety percent of all products in grocery stores contains a corn product, most commonly high fructose corn syrup, but also the majority of those ambiguous ingredients found on food packaging. If feeding cows corn spawns the evolution of bacteria, what does it do to humans? What diseases have developed as a result of this reliance on corn products, besides obesity that is?

Farmer Joel Salatin manages a sustainable farm in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, offering animal products that are raised to live off what Nature intended. Cows graze in grassy fields, and then, in turn, fertilize the land with their droppings. You know, the circle of life. Salatin simply controls which section of the field the cattle are grazing. The same goes for the pigs and chickens, both fed on natural diets and cleaned in a sanitary way. The FDA claims his open-air cleaning is unhygienic, but his products have no chemicals injected into them and they continuously beat the big corporations in terms of bacteria and contaminate traces. His method demonstrates how to use an assembly line system in an efficient, yet healthy way to provide for his customers.

The film doesn’t just promote animal rights; it spends the majority of its runtime exploring the effect these corporations have on America’s farmers. Consider the case of Monsanto soybean manufacturers. They hire men-in-black to investigate their contract farmers for seed saving, which for them is a patent infringement on genetically altered seeds. They want farmers to buy their seeds each season from the company. For the few independent farmers out there, only four types of “public” soybeans are available to grow; the hundreds of others are all owned by Monsanto. Should the company decide your farm has saved or even promoted seed saving, they’ll sue, and it’s doubtful a measly farmer’s salary could pay for the legal fees it would take to win a case against a monster like Monsanto.

But the major problem seems to be the American appetite, which, besides munching down a regular diet of unhealthy foodstuff, consumes more than it should. Our overpopulated communities consume in excess, which in turn sends a message to the corporations that there’s more demand, which in turn causes these radical-if-unsafe advances in animal production and farming to keep up, which in turn causes lesser quality food products to hit the market shelves and affect our health. The solution: Do your part. Shop at farmer’s markets whenever possible. Buy organic. Lay off the fast food. Your body will appreciate the change. So will your scale.

Emmy Award-winning director Robert Kenner guides us through a sick and corrupt business structure, introducing various chapters through ironically manufactured computer graphics. Kenner reportedly spent the majority of the film’s budget on legal fees to fend off lawsuits from food companies upset about being portrayed in a negative light. Indeed, these corporations have special libel laws protecting them, so no one can speak out against their scheming and often unsanitary practices. A Texas beef company sued Oprah Winfrey a few years ago when she slammed them on her television show, but she had the millions needed to fight back. People like Kenner, Pollan, Schlosser, and Salatin are not multi-million-dollar icons. And so it’s all the nobler, and risky, that they’re speaking out.

It’s a message that must be heard. With any luck, Food, Inc. will change the way you do your grocery shopping, causing the corporations to follow demand and begin producing healthier food at lower costs. But with America’s reliance on fast food as cheap sustenance, the fight for better chow becomes one dependent on knowledge, much like awareness campaigns that led to a pseudo-victory against Big Tobacco. Kenner’s doc does a wonderful job of opening consumers’ eyes to what they’re eating. For viewers, hopefully, the film’s effective post-screening loss of appetite develops into a life of better dietary choices.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review