Flow

By Brian Eggert |

Note: Spoilers below.

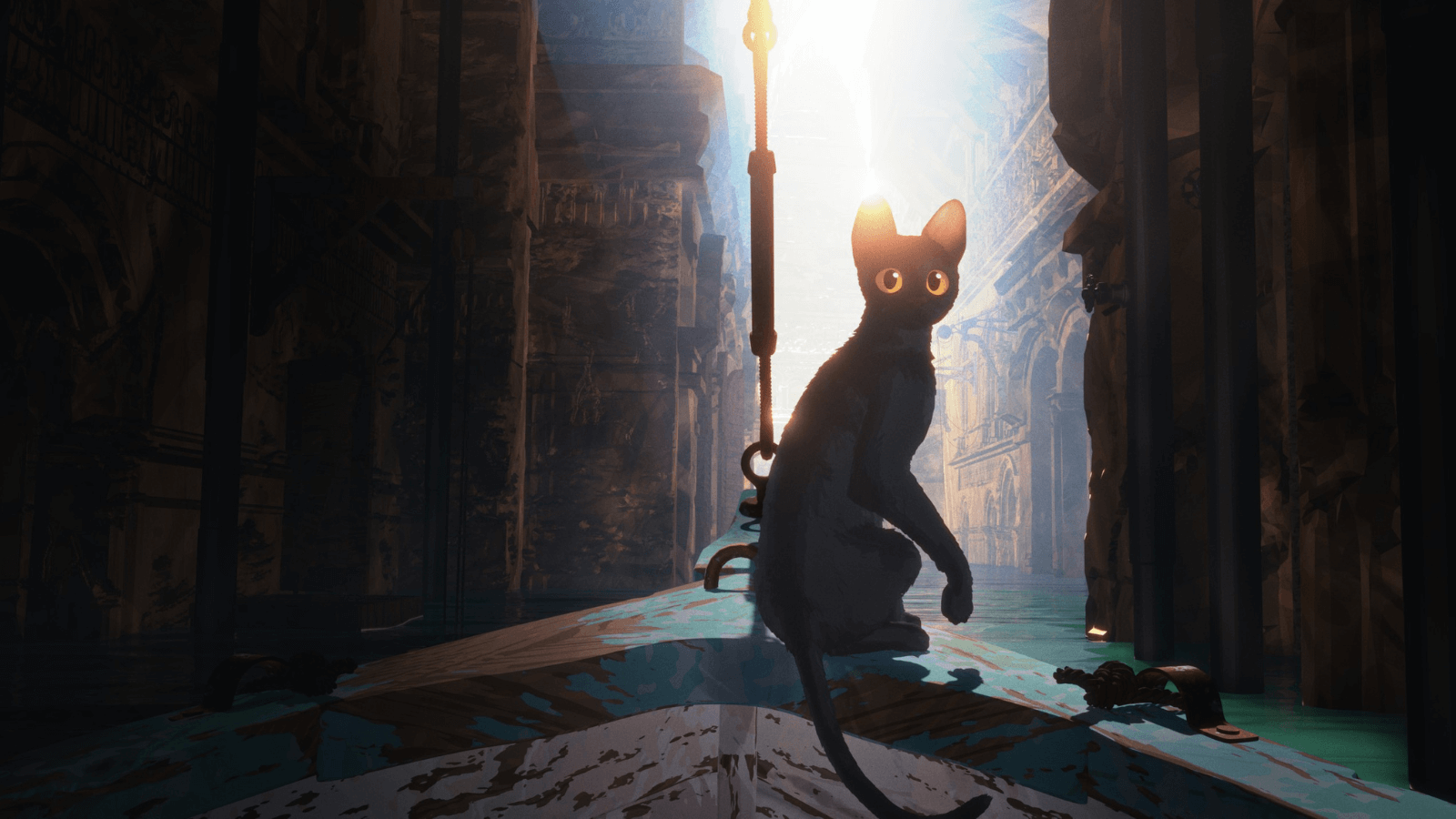

French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan coined the term mirror stage, referring to the phase in human development when someone sees their reflection and begins to understand their selfhood. It’s not only the moment when an individual starts to construct an identity, but it also introduces the mind-body dichotomy, creating a fissure between one’s sense of self and how the world perceives them. In Gints Zilbalodis’ beautiful animated film, Flow, several scenes find the protagonist, a black cat with expressive yellow eyes, looking into a reflective surface of the water and seeing itself. In the first shot, the cat is alone, experiencing Lacanian alienation. Later in the film, the cat is accompanied by other animals. Through its perilous adventure, the feline has gathered friends and cohorts; they have bonded and helped each other survive. The overwhelmingly tender moment is a testament to an individual’s role in their community, and it’s a heartwarming conclusion to this stunning work of art.

Consider that spoiler my way of answering the persistent question you’ll be asking throughout Flow. Yes, the cat lives. There’s nothing more palpitating in a movie than an animal in danger, and this is true even among animated creatures. The animals in Zilbalodis’ film, Latvia’s entry for Best International Feature at next year’s Academy Awards, face all manner of trials. Their post-human world shows traces of a long-gone humanity in ruined structures, rickety boats, and broken knick-knacks. The central cat lives in a forest home, apparently once owned by a worshipful cat enthusiast who spent their time making wooden sculptures, stone carvings, and even vast monuments to felines. Almost instantly in this 84-minute film, a rush of water floods the surrounding area, leaving the contrarian, independent cat to escape to higher ground—taking refuge on a monument to itself. But the animal must soon abandon its lifelong solitude and embrace others to survive.

An unlikely, dialogue-less posse forms after the cat joins a smart but languid capybara on a boat. Others soon accompany them: a yellow Labrador with perpetually playful energy; a lemur with an affinity for collecting human objects, such as empty containers and utensils; and a noble secretary bird who imparts the value of bonding with other species. Each has an unmistakable personality rooted in familiar animal behaviors. Their communal dynamic finds them working together, even problem-solving in a manner that approaches but does not cross the line of anthropomorphism—such as commanding their boat’s rudder. Other animals help or disrupt their journey. An enormous whalelike sea creature seems to follow them, conveniently making itself known when needed. A pack of dogs, to which the Labrador once belonged, hungrily and clumsily ruin the communal harmony on the boat.

Zilbalodis receives credit as director, co-writer, co-producer, art director, cinematographer, composer, and editor, among other attributions. His computer-generated animation style draws from video games instead of the look common among the big animation houses, giving Flow a pixelated, digital quality that occasionally betrays the otherwise dazzling presentation. For instance, the dogs, particularly their mouths, look unconvincing, whereas larger movements look natural. Occasionally, it looks as though the animals are being propelled by computer software rather than moving one foot after another. But then, the aesthetic is stylized and not reaching for photorealism. Reminiscent of the excellent 2022 game Stray, where the player guides a cat through a humanless post-apocalypse, I felt a compulsion to pick up a controller while watching Flow. Even so, the film offers luminous displays of light, atmosphere, and glimmering water. The animal movements nostly appear natural, as do the sprawling landscapes and sunlight. There’s even a touch of mysticism when one of the animals ascends through the aurora borealis to a heavenly realm.

Zilbalodis’ story could only have worked as stylized animation of this kind. Consider the alternatives. Thirty years ago, Flow might have been a troubling live-action movie similar to The Adventures of Milo and Otis (1986), a Japanese production that reportedly left an atrocious number of dead animals in its wake. A similar film with a better reputation is Jean-Jacques Annaud’s The Bear (1988), a sublime work that, like Flow, dabbles in animal dreams and visions. Thank goodness Flow wasn’t like Disney’s Homeward Bound: The Incredible Journey (1993), where animals talk through actors’ voices. Worse, it could have been like Cats & Dogs (2001), where live-action animals have animated mouths that move. Zilbalodis’ limited budget also meant he avoided the Uncanny Valley with photoreal animals, like Disney’s abortive live-action version of The Lion King from 2019.

Flow is visual storytelling at its finest, communicating without words, only animal body language and an occasionally loaded mew or bark to punctuate a moment. Accented by Zilbalodis and composer Rihards Zaļupe’s delicate score, the film communicates in volumes, conveying notes of unspoken bonds and understanding that resonate, filling the story with personality and profundity. This kind of iconic imagery opens itself to interpretation without articulating its intent as a religious metaphor or social commentary. Certainly, the film contains themes of finding one’s people, bonding through trauma, identifying with otherness, and locating harmony in Nature. However one deciphers it, this is as close to a silent film as anyone is likely to get in the twenty-first century, and it reminds us of the innate power of imagery over words.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review