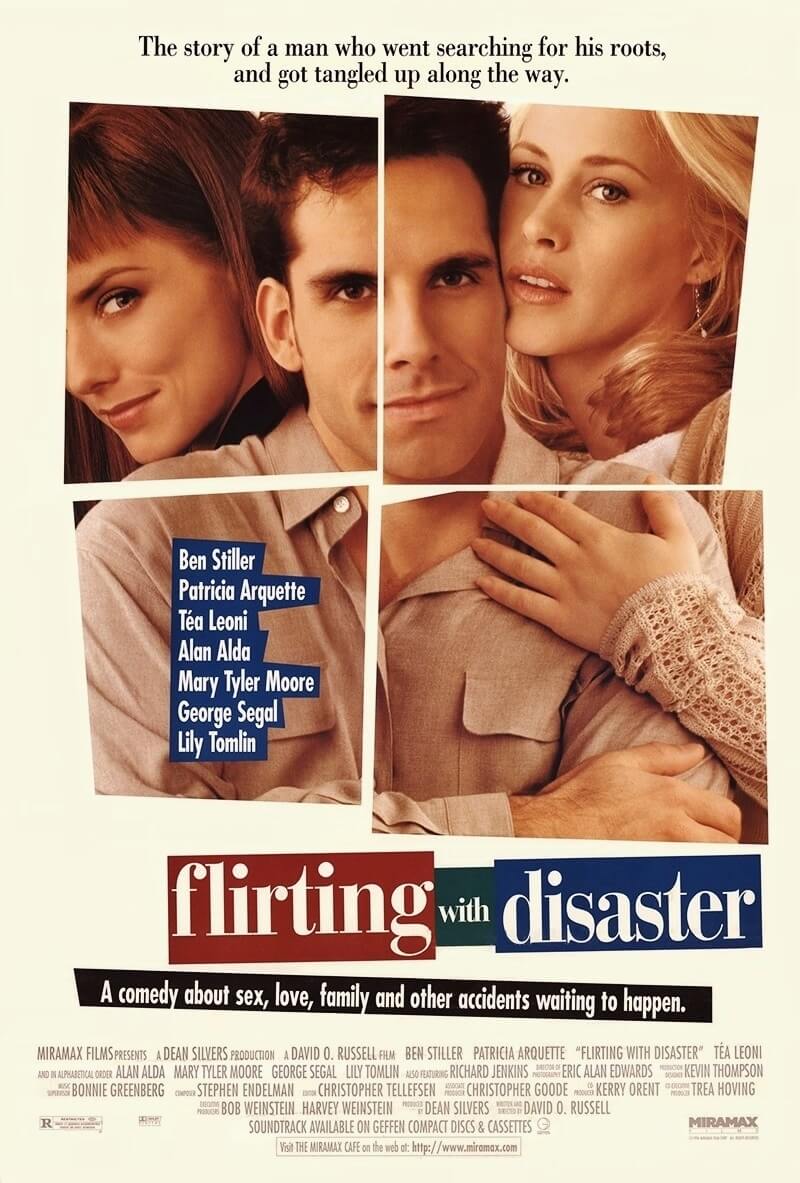

Flirting with Disaster

By Brian Eggert |

When he arrives in California to at last meet his biological mother, Ben Stiller’s staunch New Yorker Mel Coplin learns his roots originate with Valerie Swaney, a towering Southern Belle played by Celia Weston. They compare foreheads and other like qualities, and Mel feels a brief sense of self-understanding. Then he goes off and inadvertently knocks over Valerie’s display case housing countless glass animal figurines. He offers to pay for the accident, but she insists with motherly understanding that accidents like this are a miracle and part of parenthood. Later, after recounting her Confederate family history, Valerie’s identical twin daughters arrive and don their new half-brother with a free volleyball t-shirt. But then there’s a question of Mel’s age, which long-legged adoption agency rep Tina Kalb (Téa Leoni), there to document the reunion, will clear up with a phone call. Tina returns embarrassed and apologetic; she made a mistake, and Valerie is not Mel’s mother. At this, the twins ask for their t-shirt back and tell Mel to have a nice life. Valerie expects someone to pay for her glass figurines.

Family is relative in writer-director David O. Russell’s Flirting with Disaster, an existential screwball road comedy in which there are no unfunny characters, whereas standard comedies often have only one or two. Russell’s penchant for screwball situations and intelligent, Woody Allen-style dialogue both emerged and peaked in this 1996 jewel, preceding his later and more eminent work on I Heart Huckabees and Silver Linings Playbook. This film has been unjustly overlooked not because it’s underappreciated—those who’ve seen it hold it dear, and its initial critical reception was tremendously positive—but rather because it remains underseen and not a part of the canon of great modern comedies. It should be. After all, Flirting with Disaster boasts a wonderful ensemble cast of early career performances by the likes of Stiller, Leoni, Josh Brolin, and Patricia Arquette, along with venerated performers like Mary Tyler Moore, George Segal, Alan Alda, Richard Jenkins, and Lilly Tomlin. These players under this director demand moviegoers to rediscover such a criminally forgotten delight.

Russell’s film starts with a hilarious segment with Mel in Tina’s office, pondering who his biological parents might be. We see the possibilities from Mel’s head, including dignified types, a mean old hag with a hammer, and a harry shirtless man flipping the bird. To be sure, Mel has identity issues. So much so that weeks after the arrival of Mel and his wife Nancy’s (Arquette) first child, their baby boy remains unnamed. Tracking down his biological origin offends his adoptive parents (Moore and Segal), a fussy pair of New Yorkers who never stop bickering long enough to listen to Mel’s concerns. And then there’s Tina, an unstable, recently divorced woman who casually drops how she was an ex-dancer, raising Nancy’s suspicions that Mel is attracted to her. Mel, Nancy, the unnamed baby, and Tina go out to California to meet Mel’s biological parents, only to discover Tina’s mistake. She thinks the adoption agency has pinned down Mel’s father in Michigan, so they stop for yet another dead end, instead having a chance encounter with Nancy’s high school friend Tony (Brolin) and his partner-turned-lover Paul (Jenkins), both cops. Now all six of them head down to Arizona to find Richard and Mary Schlichting (Alda and Tomlin), Mel’s hippie biological parents (who were forced to give Mel up when they were busted for cooking LSD, which they still cook), and their other son, Mel’s brother, the passive aggressive Lonnie (Glenn Fitzgerald). Swingers themselves, Richard and Mary immediately notice the attractions between Mel and Tina, as well as Nancy and Tony, all of which finally come to a head over laced quail.

Russell’s film starts with a hilarious segment with Mel in Tina’s office, pondering who his biological parents might be. We see the possibilities from Mel’s head, including dignified types, a mean old hag with a hammer, and a harry shirtless man flipping the bird. To be sure, Mel has identity issues. So much so that weeks after the arrival of Mel and his wife Nancy’s (Arquette) first child, their baby boy remains unnamed. Tracking down his biological origin offends his adoptive parents (Moore and Segal), a fussy pair of New Yorkers who never stop bickering long enough to listen to Mel’s concerns. And then there’s Tina, an unstable, recently divorced woman who casually drops how she was an ex-dancer, raising Nancy’s suspicions that Mel is attracted to her. Mel, Nancy, the unnamed baby, and Tina go out to California to meet Mel’s biological parents, only to discover Tina’s mistake. She thinks the adoption agency has pinned down Mel’s father in Michigan, so they stop for yet another dead end, instead having a chance encounter with Nancy’s high school friend Tony (Brolin) and his partner-turned-lover Paul (Jenkins), both cops. Now all six of them head down to Arizona to find Richard and Mary Schlichting (Alda and Tomlin), Mel’s hippie biological parents (who were forced to give Mel up when they were busted for cooking LSD, which they still cook), and their other son, Mel’s brother, the passive aggressive Lonnie (Glenn Fitzgerald). Swingers themselves, Richard and Mary immediately notice the attractions between Mel and Tina, as well as Nancy and Tony, all of which finally come to a head over laced quail.

Russell concocts riotous, highly quotable situations where these characters tempt one another away from and in front of each others’ spouses; all the while, the frustrating journey for Mel’s identity carries on, and everyone’s social niceties wear down. Tensions between Mel and Nancy send them to their respective outlets of Tina and Tony, leaving Paul the odd man out. Head games and childish behavior ensue. Mel observes how strong Tina’s legs look, and they decide to “Indian leg wrestle.” Tony, fascinated with Nancy’s baby and seemingly gay, shows Nancy a better way to breastfeed and brings up whether or not they’ve circumcised the child, if only for an excuse to discuss his own penis. Russell’s dialogue cleverly embeds innuendo and dances around certain subjects, elsewhere his playfulness with words is comic genius. In a discussion of Tony and Paul’s sexual relationship and the risk of AIDS, Tony remarks, “Me, I’m very anal, in that I don’t want anything penetrating my body.” No end of inappropriate and awkward conversation persists, often through arguments and overlapping dialogue, which Russell writes and orchestrates to perfection. The situations reach their pinnacle when flirtations move on to acting on their impulses. Tony makes his move on the neglected Nancy, who reluctantly goes along with his desire to lick her armpit (“The depth of the pocket… So nice.”), while Tina and Mel find themselves tempted to finally act on their impulses.

After his short-lived (but no less great) sketch comedy series The Ben Stiller Show (1992-1993), his own directorial ode to Generation X with Reality Bites (1993), and bit roles abound (see Happy Gilmore or If Lucy Fell), Stiller finally found his niche playing a modern Woody Allen figure. Indeed, Stiller is point blank labeled “neurotic guy” here—after he calls out Tony and Paul for being “a couple of gay guys”—and he would continue playing such neuroses-laden roles in everything from There’s Something About Marry (1998) to Meet the Parents (2000). And yet, though it would become the launching pad for every role that followed, the popularity of his later work has overshadowed Flirting with Disaster. Everyone’s seen crud like Dodgeball and Night at the Museum, but they’ve curiously missed Stiller’s funniest and smartest film. Going back to this early career comedy today finds a scruffier, less polished Stiller (before he straightened his teeth and adopted an emaciated look) acting in a type of comedy he rarely makes anymore (i.e., something of merit).

After his short-lived (but no less great) sketch comedy series The Ben Stiller Show (1992-1993), his own directorial ode to Generation X with Reality Bites (1993), and bit roles abound (see Happy Gilmore or If Lucy Fell), Stiller finally found his niche playing a modern Woody Allen figure. Indeed, Stiller is point blank labeled “neurotic guy” here—after he calls out Tony and Paul for being “a couple of gay guys”—and he would continue playing such neuroses-laden roles in everything from There’s Something About Marry (1998) to Meet the Parents (2000). And yet, though it would become the launching pad for every role that followed, the popularity of his later work has overshadowed Flirting with Disaster. Everyone’s seen crud like Dodgeball and Night at the Museum, but they’ve curiously missed Stiller’s funniest and smartest film. Going back to this early career comedy today finds a scruffier, less polished Stiller (before he straightened his teeth and adopted an emaciated look) acting in a type of comedy he rarely makes anymore (i.e., something of merit).

The other cast members deserve equal notice; the standouts are Mel’s adoptive and biological parents. Moore (“abrasive, pushy, defensive”) and Segal (“food-phobic, passive-aggressive”) make a spot-on New York couple straight out of Woody Allen’s 1970s comedies. Alda and Tomlin, with their artistic, freethinking, anything-goes attitudes, make the artsy-fartsy couple feel genuine. But then every character feels fully realized by its respective performer, although individually, they might be best described as mere “types.” Leoni missed out on a career as a comedienne, whereas Brolin, now assigned almost exclusively to tough-guy roles, also proves he has impeccable comic instincts. Jenkins, whose ATF officer Paul goes from a hard-edged cop to a jealous spouse, carries on whole conversations with himself as the others flirt away. If you take your eyes off him, you’ll miss some of the most subtle humor in the film. This is true of every performance, making this ensemble piece something to be savored and watched numerous times to be truly appreciated.

Of course, under Russell’s sometimes notorious demand for precise dialogue delivery and adherence to his vision, the actors may have had little choice but to comply with his direction. Comic timing is essential in this setting, where multiple fleshed-out characters speak at once and send the viewer reeling to catch up to the layers of humor and neurosis and sarcasm at work. A favorite bit revolves around Mel’s resistance to B&Bs, where he clashes with the elderly manager about his use of the phone after 8 p.m.; Russell isn’t above physical humor either, shaking a hunk of brie or displaying Mel’s “pup tent” for a laugh. There’s also Paul, zonked on LSD, running through the desert in his underwear, shouting “You can’t catch the wind!” Almost every scene has a memorable line or amusing situation or quirk that deserves a hearty belly laugh. This is a comedy moviegoers can watch repeatedly and laugh every time, as the spectrum of humor isn’t limited to brainy or physical or base or wit, but rather all of them.

Of course, under Russell’s sometimes notorious demand for precise dialogue delivery and adherence to his vision, the actors may have had little choice but to comply with his direction. Comic timing is essential in this setting, where multiple fleshed-out characters speak at once and send the viewer reeling to catch up to the layers of humor and neurosis and sarcasm at work. A favorite bit revolves around Mel’s resistance to B&Bs, where he clashes with the elderly manager about his use of the phone after 8 p.m.; Russell isn’t above physical humor either, shaking a hunk of brie or displaying Mel’s “pup tent” for a laugh. There’s also Paul, zonked on LSD, running through the desert in his underwear, shouting “You can’t catch the wind!” Almost every scene has a memorable line or amusing situation or quirk that deserves a hearty belly laugh. This is a comedy moviegoers can watch repeatedly and laugh every time, as the spectrum of humor isn’t limited to brainy or physical or base or wit, but rather all of them.

More accessible than I Heart Huckabees and less mainstream than Silver Linings Playbook, Flirting with Disaster is an indie comedy that demands to be rediscovered and reevaluated by audiences as one of cinema’s most blithely daft, complex, and purely funny comedies of the 1990s. Amid Russell’s masterful timing, the actors’ turbulent performances, and the quotably clever dialogue, there’s also a tender center. Tina offers the film’s essential theme: “Every marriage is vulnerable, otherwise being married wouldn’t mean anything, would it?” We see those limits tested and dangled here, in time discovering the strength of the relationships presented. With ubiquitous screwball situations and existential searching, Russell’s characters spend the entire film in flux, lost, and somewhat aimless until they realize how they’ve all gone too far. Every relationship has had these moments, and it’s our ability to experience, live through, and eventually laugh about them that makes a relationship strong. Russell’s deceptively wise film sustains those insane, out-of-touch moments of behavior and prolongs them, making the experience torturously funny, but rewarding on multiple levels.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review