Flamin’ Hot

By Brian Eggert |

Note: This review was originally published for the 2023 Minneapolis St. Paul International Film Festival and has been expanded.

If you watch Flamin’ Hot in a vacuum, knowing nothing else about the story other than what the movie presents, then you’re in for “a crowd-pleasing tale of billion-dollar ingenuity.” That’s how I described the film over a month ago, reporting from the Minneapolis St. Paul International Film Festival. The story comes from Richard Montañez, the self-mythologizing Frito-Lay executive who claims to have invented the spicy Flamin’ Hot snack flavor. In Montañez’s 2021 book, Flamin’ Hot: The Incredible True Story of One Man’s Rise from Janitor to Top Executive, he spins a yarn about working at Frito-Lay’s Rancho Cucamonga plant, where he conceived of the potent red powder that has become wildly popular on Cheetos. Montañez followed his career in the snack industry as a speaker-for-hire at major companies and Ivy League schools, presenting with the convincing charisma of a practiced orator. After all, what a story—a rags-to-riches tale about a Mexican-American underdog who became a top executive. But a quick Google search presents a wrinkle in Montañez’s account, which raises questions about how we should view the movie.

Eva Longoria makes her directorial debut with Flamin’ Hot, where Jesse Garcia plays Montañez, the film’s narrator who charts his rise from a bullied schoolboy to a drug-dealing car thief to a maintenance crew member at a Frito-Lay factory in California. Coming from a blue-collar background and starting without a diploma, Montañez recounts a version of the American Dream that few have been fortunate enough to experience. He gives credit to those around him—namely, to his ever-supportive wife Judy (Annie Gonzalez), their children, and several coworkers. These include his lightly racist manager (Matt Walsh), who hires Montañez; the machinist (Dennis Haysbert) who indulges Montañez’s curiosity about all aspects of the factory’s inner workings; and PepsiCo CEO Roger Enrico (Tony Shalhoub), who takes the janitor’s call and listens to his wild ideas about spicy Cheetos, Doritos, and Fritos. Montañez is a compelling hero, and rooting for him in the film is easy.

But according to several reports, after Montañez began telling his story in public venues, the company performed an internal investigation in 2018. “None of our records show that Richard was involved in any capacity in the Flamin’ Hot test market,” Frito-Lay explained in a statement to the Los Angeles Times in 2021. “That doesn’t mean we don’t celebrate Richard, but the facts do not support the urban legend.” So the question remains: Do you believe the big corporation, or the former employee who’s an admitted teller of tall tales? And if Frito-Lay’s claim is true, does any of this matter? Certainly, one could take a “print the legend” stance on the subject without decrying what might range from exaggeration to outright deception. It’s true, for instance, that Montañez started as a janitor and was promoted through the corporate ranks. And it’s common for biopics and movies based on historical events to play fast and loose with the facts. So how is Flamin’ Hot any different? He may not be Clifford Irving, but to draw a comparison to another figure in Orson Welles’ F for Fake (1974), Montañez may have something in common with Elmyr de Hory.

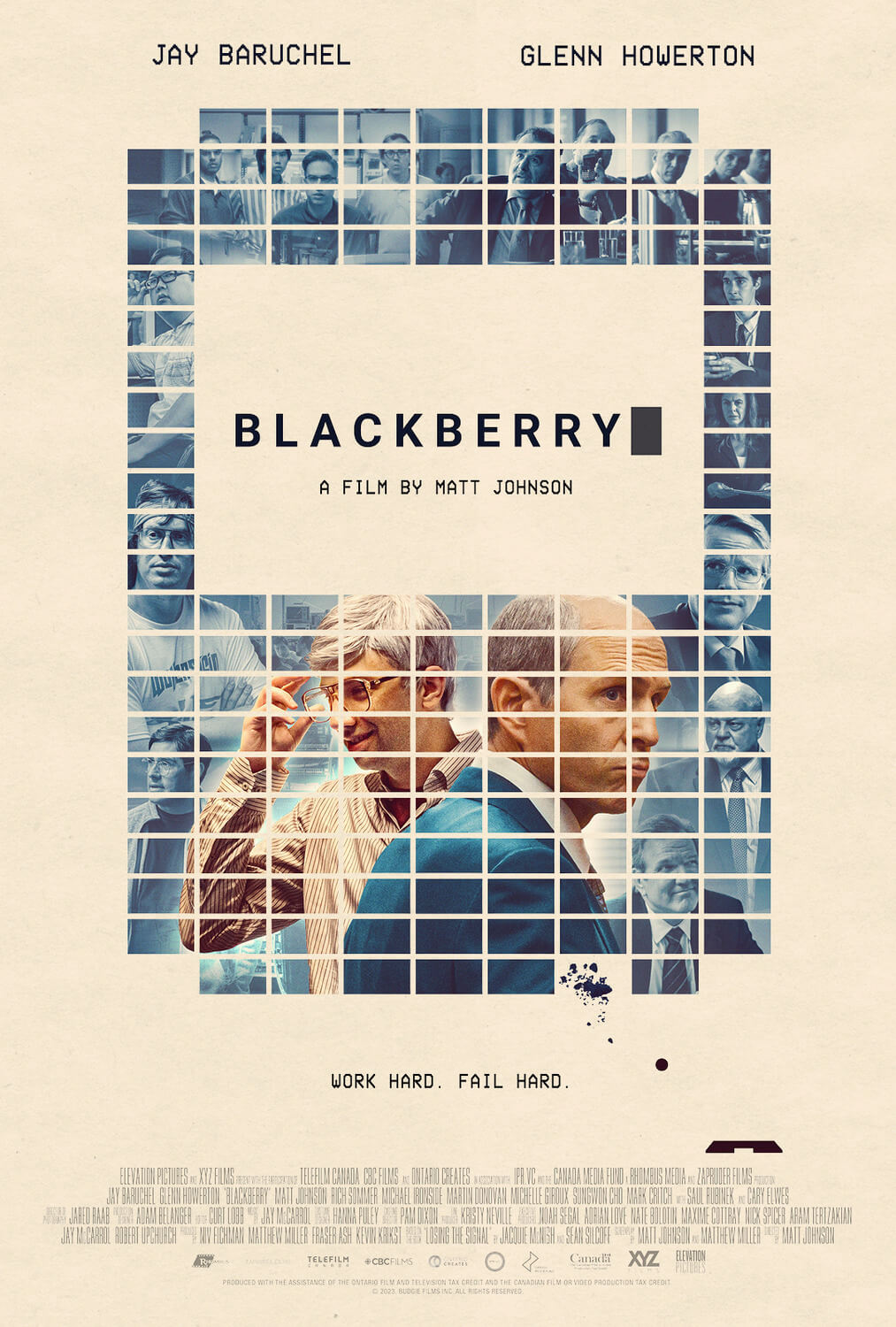

Although the filmmakers have acknowledged the accusations against Montañez, they resolved to make Flamin’ Hot anyway. Given this, it’s unclear whether the screen story is meant to be a feel-good comedy about Montañez or an origin story for a product beloved by many. More than its 2023 contemporaries in the brand biopic subgenre—Tetris, Air, Blackberry—Longoria’s film approaches its commercial subject with heart to spare, relying on Montañez’s sense of family and pride about his Mexican heritage. Although the formal execution often lacks stylistic polish, the energy and passion of the filmmaking, along with the thematic and sociopolitical undercurrents of the story, elevate the movie beyond its presentation. The screenplay by Lewis Colick and Linda Yvette Chávez draws from Montañez’s Flamin’ Hot and his first book, A Boy, a Burrito, and a Cookie from 2013. From there, Longoria fashions scenes with the same enthusiasm that Montañez writes and conducts his speaking engagements.

Although the filmmakers have acknowledged the accusations against Montañez, they resolved to make Flamin’ Hot anyway. Given this, it’s unclear whether the screen story is meant to be a feel-good comedy about Montañez or an origin story for a product beloved by many. More than its 2023 contemporaries in the brand biopic subgenre—Tetris, Air, Blackberry—Longoria’s film approaches its commercial subject with heart to spare, relying on Montañez’s sense of family and pride about his Mexican heritage. Although the formal execution often lacks stylistic polish, the energy and passion of the filmmaking, along with the thematic and sociopolitical undercurrents of the story, elevate the movie beyond its presentation. The screenplay by Lewis Colick and Linda Yvette Chávez draws from Montañez’s Flamin’ Hot and his first book, A Boy, a Burrito, and a Cookie from 2013. From there, Longoria fashions scenes with the same enthusiasm that Montañez writes and conducts his speaking engagements.

How appropriate, then, that Longoria embraces his imagination and showmanship. Montañez’s narration gives way to lively but all too familiar sequences of daydreaming and exaggeration. In a trick borrowed from both Comedy Central’s Drunk History and Michael Peña’s character in Ant-Man (2015) and Ant-Man and the Wasp (2018), Montañez’s voiceover provides the dialogue to his bombastic accounts of executive meetings. Then, the otherwise bland white men in suits act out Montañez’s version of events, their mouths synching with his slang dialogue to deliver a hilarious visual incongruity. But it’s not exactly an original technique, leaving the viewer amused and somewhat distracted by its derivativeness. However, in the context of the film as truth, the method reveals the degree to which Montañez bends the truth, if not entirely alters the details to make the story more entertaining. Still, while one might expect a Big Fish story to change the size of the catch in the storyteller’s favor, they wouldn’t expect that the fisherman never caught a fish at all.

Even so, Garcia and Gonzalez have plenty of charm and a palpable rapport, and they drive the movie. But Longoria also injects an unspoken yet worthy agenda into the proceedings, offering a counterargument to those who would discriminate against Mexican-American workers, anyone without a high-school education, or line-level employees as people incapable of creative or innovative contributions to a business. As Montañez proves—at least, in this fictionalized account—anyone can follow Enrico’s suggestion to “think like a CEO.” However, not everyone has the ambition to act on these thoughts with the enthusiasm and determination to make them happen. Even if Montañez wasn’t the inventor of the title’s snack flavor (the real origins of the flavor are banal), his success story is a fun watch. Extratextually, however, Flamin’ Hot becomes a kind of test, not unlike the one presented in Ang Lee’s Life of Pi (2012), that questions what kind of stories you prefer: those with uneasy and even depressing facts, or false stories that keep you entertained. Longoria and company have made their choice. What’s yours?

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review