First Cow

By Brian Eggert |

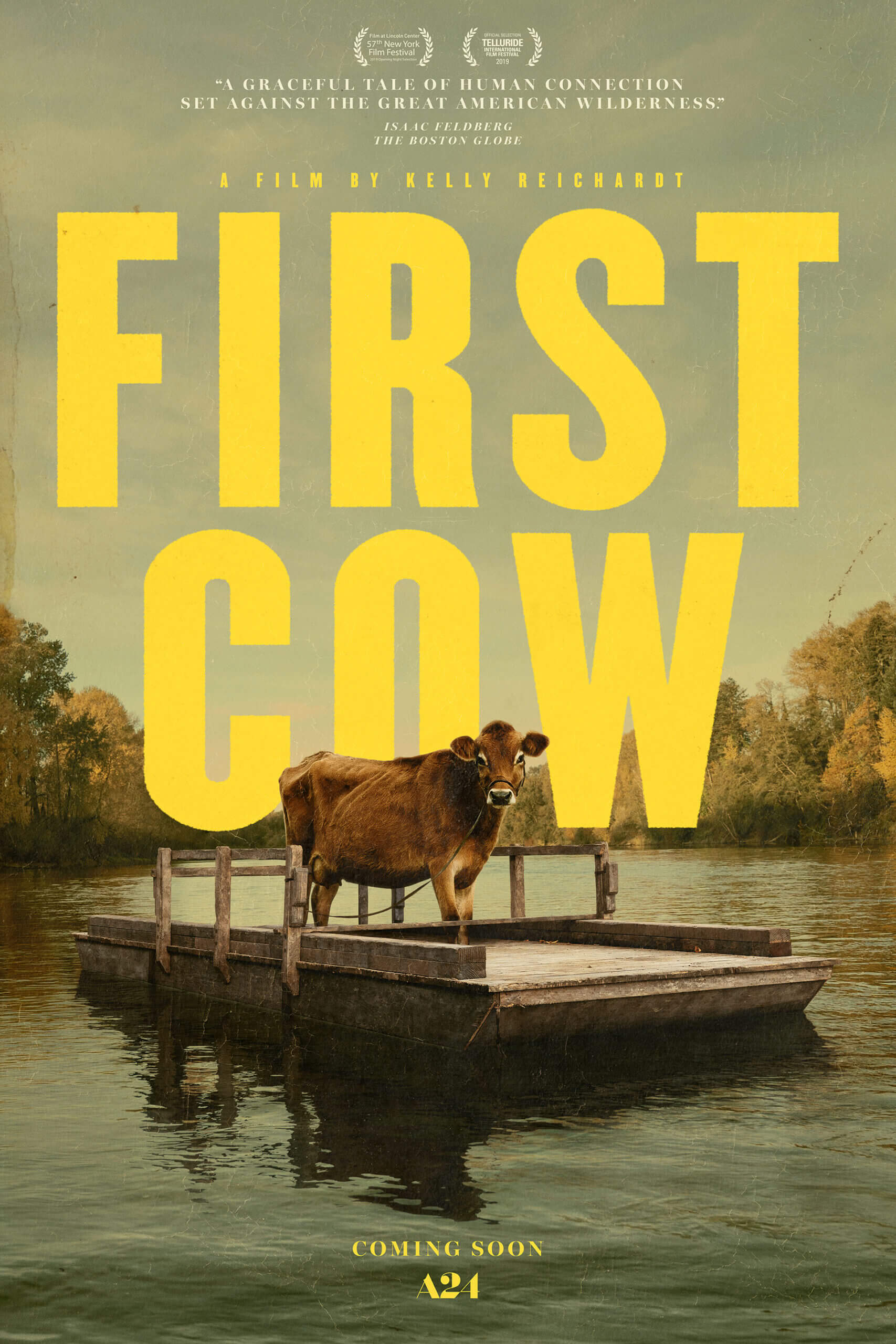

Somewhere deep inside a Pacific Northwest forest, in the 1820s, years before migrant wagon trains would take the Oregon Trail and begin to settle the area, a man forages for mushrooms. He walks quietly among the damp trees and ferns, picking orange chanterelles and other mycological delicacies to prepare for his trapping party. The other, more rugged men in their outfit head westward in search of opportunity and beaver pelts. “Cookie” Figowitz, played with quiet sensitivity by John Magaro, has a softer and more delicate demeanor than his infighting fellow travelers, who grumble about their hunger for meat. Browsing the lush woodland, Cookie carefully wraps each mushroom in a cloth and places them in his knapsack. Then, he finds a rough-skinned newt trapped on its pack, and he turns it over kindly and watches the amphibian wiggle away. Cookie’s gentle disposition and oneness with Nature personifies Kelly Reichardt’s First Cow, her beautifully observed film whose outward simplicity gives way to a thoughtful exploration of capitalism, and the relationship between humanity and the natural world. Soon, Cookie will meet the only milk cow in Oregon, and the bovine, with its large, guileless brown eyes, will play a central role in a small industry.

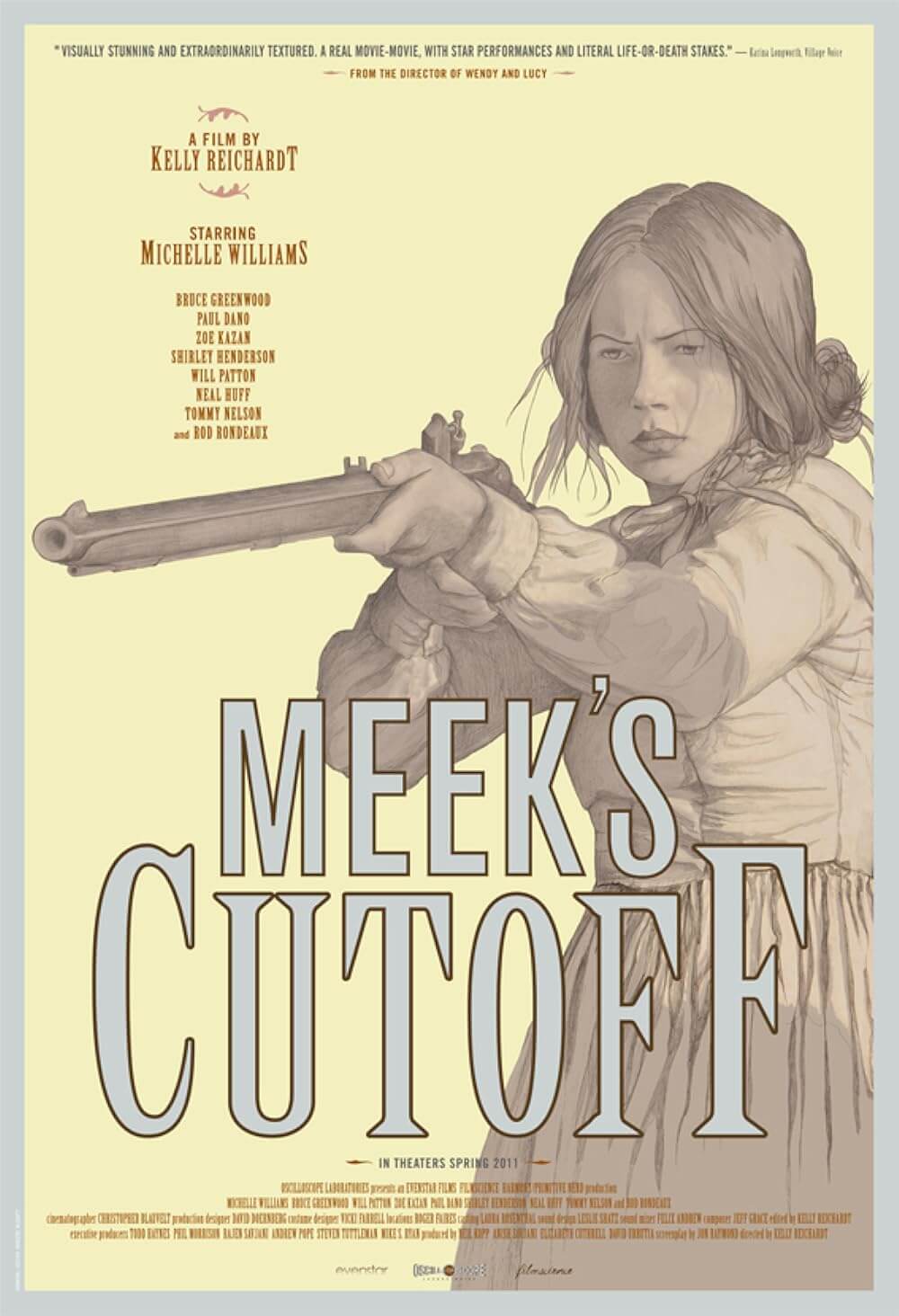

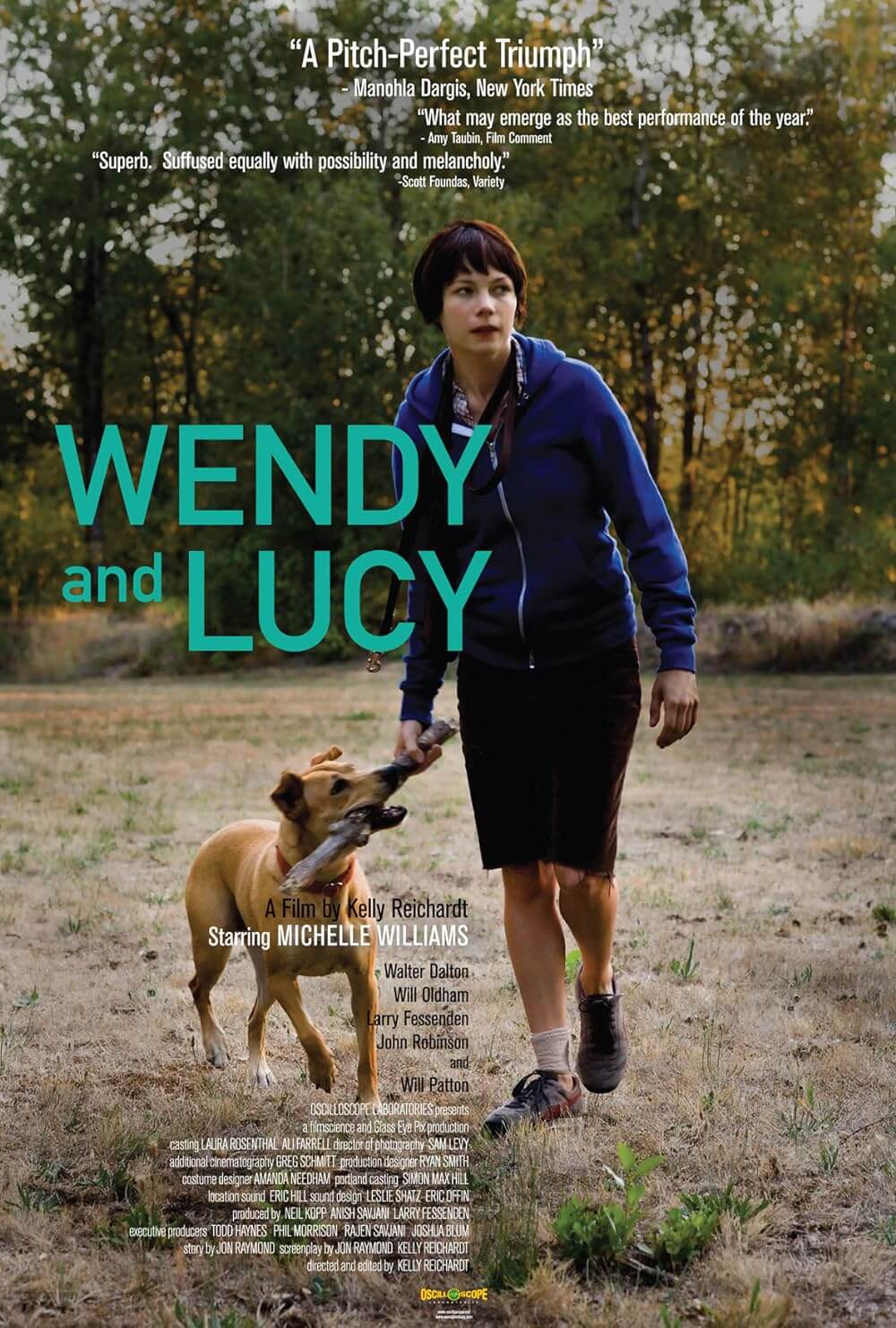

Reichardt’s film fits nicely into her continued partnership with author Jonathan Raymond, who wrote the source material for Old Joy (2006), Wendy and Lucy (2008), Meek’s Cutoff (2010), and co-wrote Night Moves (2013) with the director. Raymond’s fiction usually involves stories of Oregonian history and culture; thus, most of Reichardt’s films take place in these surroundings, save for two—her debut River of Grass (1996) and her adaptation of author Maile Meloy’s writing with Certain Women in 2016. First Cow was based on Raymond’s 2004 novel, The Half-Life, though it concentrates on the sections of Raymond’s book that take place in the nineteenth century. A compendium of his themes, the film explores male friendships as in Old Joy; the bond between a person and an animal, seen in Wendy and Lucy; the dangers experienced by frontiersmen during the push West, traversed in Meek’s Cutoff; and the corruption of the natural world by capitalistic influence at the center of Night Moves. Reichardt and Raymond’s shared concerns as authors return in this peerless rumination on how the serenity and routines of Nature, and the underlying bonds between people and their surroundings, are corrupted by humanity’s desire for profit.

Having made his way across the country from his birthplace in Maryland, Cookie stumbles onto a friend, twice. When he first meets King Lu (Orion Lee), a garrulous Chinese immigrant with a knack for business, Cookie finds him naked in the bushes, hiding from a band of Russian trappers. “I might’ve killed one of their friends,” King Lu admits. Perhaps disarmed by the man’s honesty, Cookie feeds him, gives him a place to sleep in his tent, and helps him hide. There’s no malice or judgment, signaled by William Tyler’s airy acoustic score, which settles on a soft, plucked theme when Cookie is alone with Nature. Later, after separating from his trapper companions at a nearby fort, Cookie reconnects with King Lu, and their friendship deepens. Almost immediately upon his invitation into the Chinese man’s shack, Cookie picks up a broom and begins to sweep. While King Lu chops wood for a fire, Cookie shakes out a rug and gathers some wildflowers for a small container. Their friendship is easygoing, their camaraderie enhanced by the relaxed performances from Magaro and Lee, which contain an unspoken bond between the two men. By their first evening together, they have settled into domestic rituals, telling stories about their travels, their plans to start a filbert farm or get rich after a move to San Francisco.

Having made his way across the country from his birthplace in Maryland, Cookie stumbles onto a friend, twice. When he first meets King Lu (Orion Lee), a garrulous Chinese immigrant with a knack for business, Cookie finds him naked in the bushes, hiding from a band of Russian trappers. “I might’ve killed one of their friends,” King Lu admits. Perhaps disarmed by the man’s honesty, Cookie feeds him, gives him a place to sleep in his tent, and helps him hide. There’s no malice or judgment, signaled by William Tyler’s airy acoustic score, which settles on a soft, plucked theme when Cookie is alone with Nature. Later, after separating from his trapper companions at a nearby fort, Cookie reconnects with King Lu, and their friendship deepens. Almost immediately upon his invitation into the Chinese man’s shack, Cookie picks up a broom and begins to sweep. While King Lu chops wood for a fire, Cookie shakes out a rug and gathers some wildflowers for a small container. Their friendship is easygoing, their camaraderie enhanced by the relaxed performances from Magaro and Lee, which contain an unspoken bond between the two men. By their first evening together, they have settled into domestic rituals, telling stories about their travels, their plans to start a filbert farm or get rich after a move to San Francisco.

Other men around the fort have not done so well. Look at the mumbling old codger, played by the late René Auberjonois, whose crumbling shack and ominous raven on his shoulder underscore the necessity for ingenuity. Fortunately, King Lu has a scheme, compelled by Cookie’s dreamy desire for buttermilk biscuits. Not long ago, a wealthy Englishman, Chief Factor (Toby Jones), ordered cows from San Francisco. The bull and calf died during the long journey, but the remaining female (real name Evie) supplies the resident nobleman—who lives in an ornate house with Native American servants—with milk for his tea. King Lu hatches a plan to sneak onto the Chief’s property and keep a lookout while Cookie milks the cow, acquiring just enough milk to make biscuits. With few delicacies at the fort aside from whiskey and meat, King Lu realizes they can sell the biscuits for a hefty profit. Their fringe business grows further when Cookie, once indentured to a baker in Boston, delivers sweeter deep-fried “oily cakes” drizzled with honey and dusted with freshly grated cinnamon. Hardened trappers line up and empty their pockets for “a taste of home,” creating a lucrative enterprise. Still, a business that thrives from stolen milk is inherently dangerous. “So is anything worth doing,” argues the ambitious King Lu, who does the math: “Another cup, another dozen cakes, another 60 silver pieces at least.” He’s blinded by the possibilities.

Reichardt, who serves as editor, lends First Cow a gorgeous and calming visual treatment. Even though the closest temporal comparison in her work is Meek’s Cutoff, the film has more in common visually with Old Joy’s scenes around the secluded hot springs in the Pacific Northwest mountains. Shooting in predominantly natural light, Christopher Blauvelt, the cinematographer on Reichardt’s previous three films, captures the green, muddy, thriving, and idyllic surroundings with grace. Nature itself feels unspoiled, and the sight of a human being on the river, for instance, rowing in a canoe, his dog standing like a ship figurehead at the front of the boat, is a rare thing indeed. Reichardt holds shots longer than the average director, allowing the viewer to feel immersed in the setting. Whereas every other person feels like an invader, Cookie seems like he could coexist with his environment. Watch the scenes shot in the blackness of night, when Cookie approaches the Chief Factor’s cow to steal her milk. He compliments her beauty and talks to her like a widow. “Sorry about your husband,” he says, smiling at her and making a connection. He gently milks her, and then he thanks her with sincerity. It’s an uncommonly stunning film in such moments, yet it also emphasizes the fragility of Nature against the exploitative drives of so-called civilization.

The scenes inside the Chief Factor’s home offer a sharp contrast to Cookie’s unobtrusive presence onscreen and his effortless, unprejudiced friendship with King Lu. Having enjoyed one of Cookie’s desserts (“I taste London in this cake”), the Chief commissions him to bake a blueberry clafoutis for the visiting Captain (Scott Shepherd). The tea-time conversation between the two well-to-dos entails a debate about the benefits of corporal punishment, if not execution, to set an example, and then transitions into how Parisian fashion will shape the demand for beaver pelts. When Cookie arrives with the dessert, he is treated like the help, whereas King Lu’s otherwise intelligent remarks are seen as subhuman given their source. In every way that matters, these self-important officials do not belong in this territory. And soon enough, the dangerous game, where Cookie and King Lu profit from the stolen milk from Chief Factor’s cow, leads to their inevitable exposure. But Lu’s rationalization to “take what’s ours while the taking is good” is ultimately the same logic that fuels American capitalism and continues to squander resources. It’s the same impulse that led to countless boom towns going under and mines being tapped out; it also leads to deforestation and the corruption of rivers to support hydroelectric dams. By contrast, there’s something peaceful and genuine in the brief moments between Cookie and the cow, something approximating balance.

The scenes inside the Chief Factor’s home offer a sharp contrast to Cookie’s unobtrusive presence onscreen and his effortless, unprejudiced friendship with King Lu. Having enjoyed one of Cookie’s desserts (“I taste London in this cake”), the Chief commissions him to bake a blueberry clafoutis for the visiting Captain (Scott Shepherd). The tea-time conversation between the two well-to-dos entails a debate about the benefits of corporal punishment, if not execution, to set an example, and then transitions into how Parisian fashion will shape the demand for beaver pelts. When Cookie arrives with the dessert, he is treated like the help, whereas King Lu’s otherwise intelligent remarks are seen as subhuman given their source. In every way that matters, these self-important officials do not belong in this territory. And soon enough, the dangerous game, where Cookie and King Lu profit from the stolen milk from Chief Factor’s cow, leads to their inevitable exposure. But Lu’s rationalization to “take what’s ours while the taking is good” is ultimately the same logic that fuels American capitalism and continues to squander resources. It’s the same impulse that led to countless boom towns going under and mines being tapped out; it also leads to deforestation and the corruption of rivers to support hydroelectric dams. By contrast, there’s something peaceful and genuine in the brief moments between Cookie and the cow, something approximating balance.

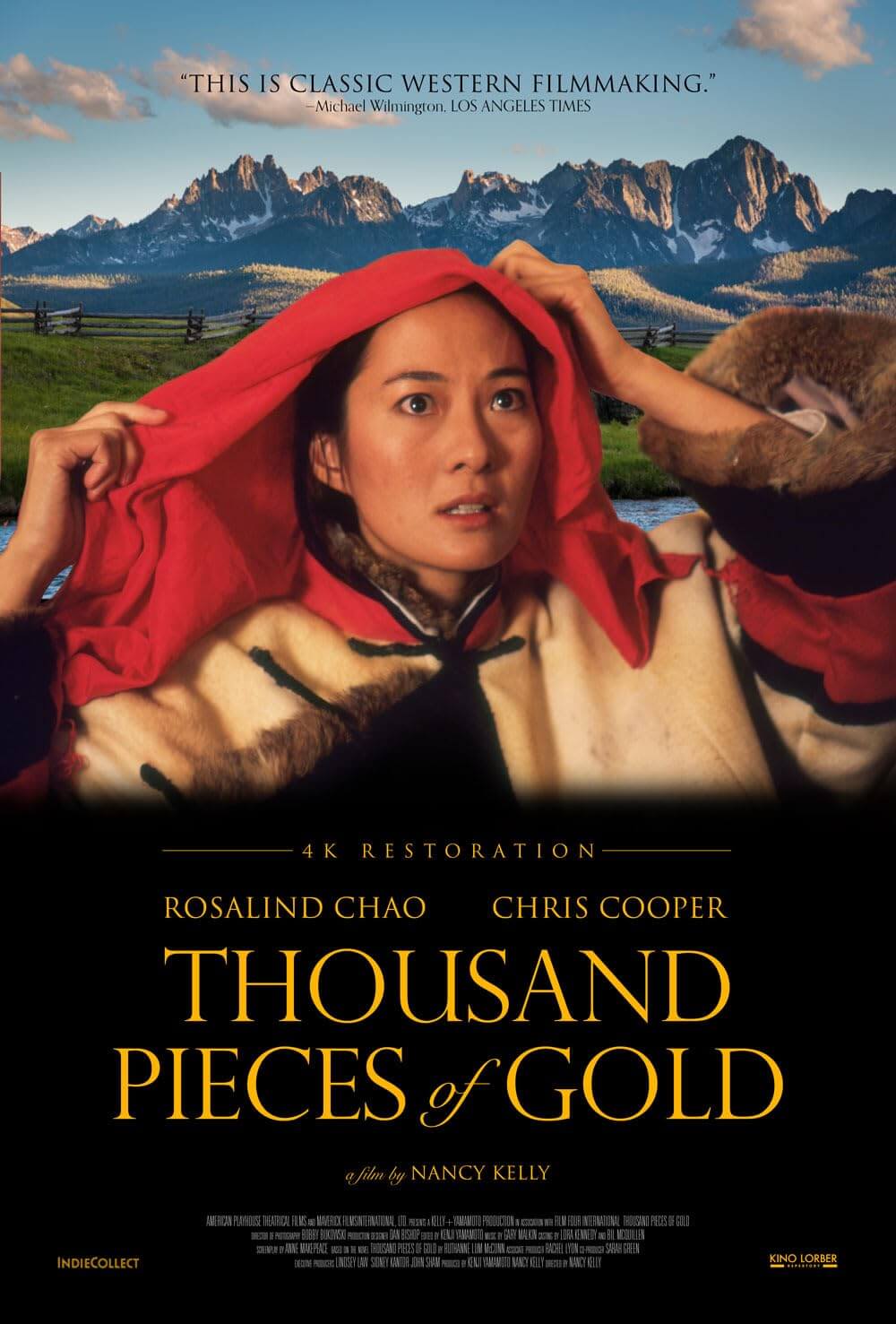

Despite the period and its setting, First Cow deviates from traditional Western genre tropes just as Meek’s Cutoff does. Both Reichardt films consider the folly of America’s ambition to achieve its Manifest Destiny, the conquering of the Wild West in service of white civilization, and the costs in terms of humanity and Nature. The initial hope of owning history to create something new ultimately descends into a disaster when greed and ambition violate the New World, repeating the mistakes of the past in different scenery. The same is true of Anthony Mann’s Bend of the River (1952) or Nancy Kelly’s underseen Thousand Pieces of Gold (1990), two films that consider how settlers in the West sought to commodify every natural or human resource for profit until they have been wasted away. These titles prove not merely revisionist but on the margins of Westerns, eschewing the usual gunfights and showdowns found in the genre. Instead, they investigate the corruptive impulses of humankind as violent, unnatural aggression on the frontier they hope to tame. Whereas most Westerns use Nature as a symbol of the savagery and wild tenor that demands to be civilized by human laws, these films consider people to be the wild and untamed forces in the West.

Even so, Reichardt once again offers her assurance that Nature will correct itself. In the first frames of her film, set in contemporary times alongside a river busy with massive transport barges, a young woman (Alia Shawkat) and her dog walk through the woods and find something buried just under the surface. She pulls away the dirt to reveal two skeletons lying next to each other in a shallow grave. First Cow does not need to return to this contemporary setting later to identify these bodies; the implications are clear, and the viewer can fill in the blanks. More telling are the parallels between the small wooden barge that transports Evie to her new home in Oregon and the monstrous metal boat that gradually crosses Blauvelt’s boxy, Academy ratio frame—the same confining view that Reichardt uses in Meek’s Cutoff to raise our awareness of her fable as a historical allegory. Given her film’s mournfulness toward the once-abundant resources of the land, and its criticism of those who would fight and die for ownership of its bounties, these images remain a powerful reminder that Nature restores itself, and it will continue long after humanity’s jealous attempts to own the land and its creatures have been buried and forgotten.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review