Filmworker

By Brian Eggert |

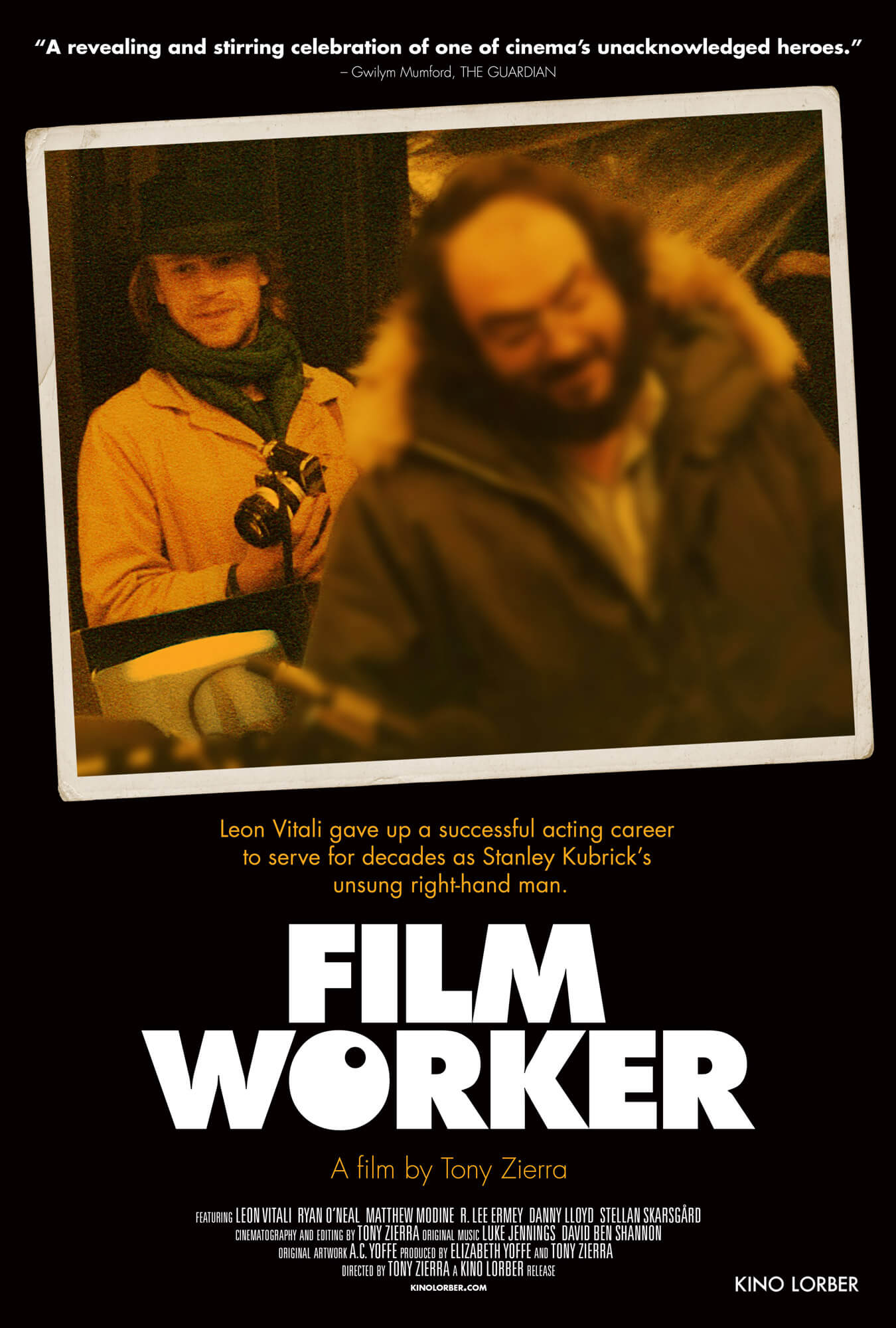

Behind every auteur are countless overlooked artists and technicians who bring the director’s vision to life, while also adding their own touches to the overall production. It’s why cinema remains the great collaborative artform. Leon Vitali served as the personal assistant to perhaps the most idiosyncratic and mythic auteurs in film history, the reclusive Stanley Kubrick. Vitali carried out a myriad of jobs for Kubrick, including talent scout, acting coach, photographer, research assistant, marketer, color timer, and manager of every single print of any Kubrick film shown theatrically the world over. Vitali had so many jobs that when he traveled and required a visa, in the occupation section, he wrote “filmworker,” as no other title encompassed everything he did. That’s also the title of Tony Zeirra’s documentary about Vitali, the man most closely connected to Kubrick in the latter part of his career.

Filmworker offers another glimpse into Kubrick’s enigmatic and isolated world through Vitali, who served as the instrument of his employer’s perfectionism for decades. Throughout the early 1970s, Vitali started in show business as an actor. With the look of Mick Jagger and talent enough for British theater and television, he had the makings of a star. Vitali saw Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and was blown away, but after seeing A Clockwork Orange (1971) theatrically, he told his friend, “I want to work for that man.” Not long after, Vitali was cast as Lord Bullingdon in Kubrick’s enigmatic costume drama Barry Lyndon (1975), playing a despicable character that made even the titular, deeply selfish protagonist seem tolerable. Watching Kubrick work, Vitali realized he wanted to learn the craft. He told Kubrick as much and, surprisingly, the director encouraged him. Not long after securing a gig editing Terror of Frankenstein (1977), in which he starred as the mad scientist, Vitali was asked by Kubrick to help on his upcoming production of The Shining.

Vitali would be instrumental in lending distinct details to Kubrick’s last three productions, beginning with The Shining in 1980, then Full Metal Jacket (1987) and Eyes Wide Shut (1999). On The Shining, Vitali found child actor Danny Lloyd and coached him, but also came up with the idea of having creepy twins girls play Grady’s daughters. He worked closely with R. Lee Ermey to develop his iconic drill sergeant role. During this time, he served as a liaison between Kubrick and Warner Bros. executives, managing the fastidious details and meticulous audio-visual transfer processes of every Kubrick film to home video. And in addition to his countless other tasks on any given production, he starred as the grand master of the notorious orgy scene in Kubrick’s final film. Despite the renown for Kubrick’s imposing genius, it turns out he was also a fantastic delegator. “I never handled Stanley,” says Vitali at one point, “I handled myself, so I could exist in Stanley’s world.”

Kubrick’s sometimes compulsive attention to detail meant Vitali rushed from one task to the next, working fourteen-hour days only to return home and spend another eight hours on the phone, ensuring Kubrick’s stipulations were met, often sacrificing sleep and time with his children in the process. When he did sleep, he barely relaxed, worrying that he might face his employer’s occasionally vitriolic wrath should he miss some essential detail. And yet, Kubrick had a charisma about him that engendered loyalty, while also making everyone who encountered him feel they had just met “the real Stanley.” Filmworker shows us Vitali’s version of “the real Stanley.” Whether Kubrick was a Machiavellian manipulator of people or simply a “chess player” as the film suggests, Vitali was dedicated to helping the director bring his vision to the screen, regardless of his peculiarities, some of which are discussed in this documentary. The result wore on Vitali. Now in his sixties, Vitali, under a bandana like an aged rock-n-roller, appears gaunt, his eyes sunken, his skin weathered.

Kubrick’s sometimes compulsive attention to detail meant Vitali rushed from one task to the next, working fourteen-hour days only to return home and spend another eight hours on the phone, ensuring Kubrick’s stipulations were met, often sacrificing sleep and time with his children in the process. When he did sleep, he barely relaxed, worrying that he might face his employer’s occasionally vitriolic wrath should he miss some essential detail. And yet, Kubrick had a charisma about him that engendered loyalty, while also making everyone who encountered him feel they had just met “the real Stanley.” Filmworker shows us Vitali’s version of “the real Stanley.” Whether Kubrick was a Machiavellian manipulator of people or simply a “chess player” as the film suggests, Vitali was dedicated to helping the director bring his vision to the screen, regardless of his peculiarities, some of which are discussed in this documentary. The result wore on Vitali. Now in his sixties, Vitali, under a bandana like an aged rock-n-roller, appears gaunt, his eyes sunken, his skin weathered.

If there’s anything missing from the 94-minute documentary, it’s Kubrick’s famously unrealized projects that came and went over the years. Kubrick long considered making the monumental story of Napoleon, which has since been slated for a miniseries by HBO. He also sought to make a film about the Holocaust, spending years doing research and contacting potential screenwriters for an original investigation into the atrocities of the Second World War; but he scrapped his ideas after seeing Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List (1993), believing he could do no better. In the late 1970s, Kubrick began conceiving a science-fiction story about artificial intelligence, an idea that he developed for decades because special FX technology could not yet realize his vision. Although his film was never produced, Steven Spielberg eventually picked up where Kubrick left off and made A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001). Unfortunately, Filmworker doesn’t explore these unrealized projects or suggest that Vitali played any role in Kubrick’s extensive research, but undoubtedly he did.

Several documentaries have contributed to the lasting myth and fanaticism around Kubrick since his death. Everything from Stanley Kubrick’s Boxes (2008) to Room 237 (2012) have sought to explore the intricate and mysterious frame of mind of this most enduring director. Zeirra’s film offers an example of the human toll that went into Kubrick’s films and life through the portrait of Vitali. Zierra combines archival photography, behind-the-scenes footage, extensive interviews with Kubrick’s actors and Vitali’s family, and clips from Vitali’s acting work to assemble Filmworker. Perhaps best of all, the documentary, while probing its subject and offering a unique glimpse into a behind-the-scenes figure, celebrates such “below the line” crewmembers. Filmworker reminds us that even the most pronounced auteurs require collaborators, and crewmembers like Vitali love their work and don’t really mind the personal sacrifices needed to make great art.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review