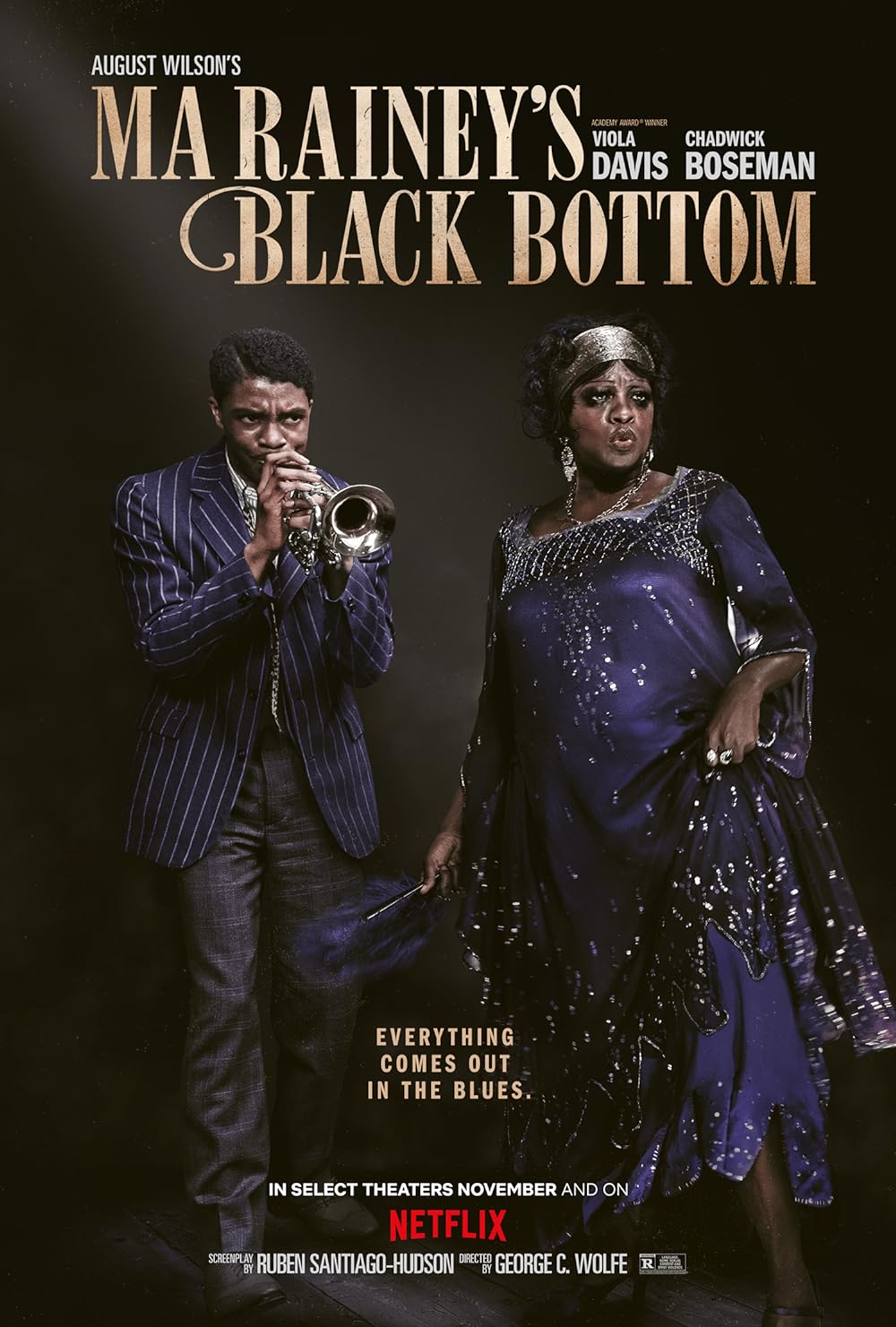

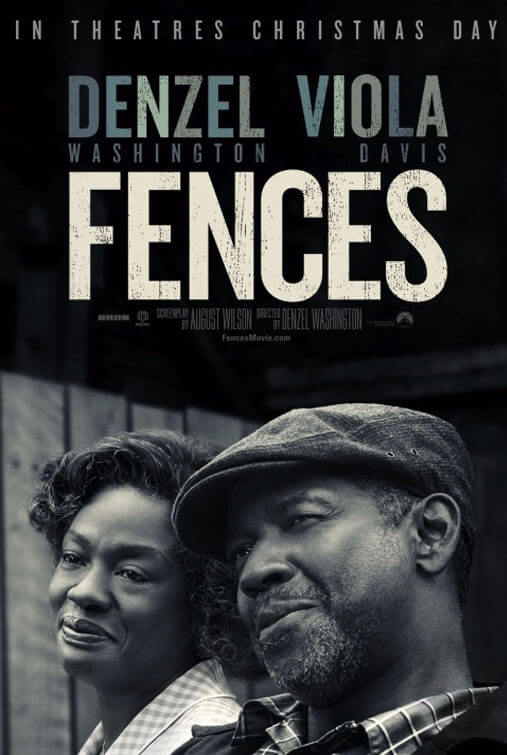

Fences

By Brian Eggert |

Fences premiered in 1985 as part of playwright August Wilson’s Pittsburgh Cycle, a series of ten plays, each of which considers the African-American experience in a specific decade throughout the twentieth century. Fences arrived in the middle, taking place in the 1950s, though the plays debuted between 1982 and 2003. Wilson’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play introduced theatergoing audiences to Troy Maxson (originally played by James Earl Jones), who bears undeniable similarities to Arthur Miller’s Willy Loman from Death of a Salesman. Troy speaks in longwinded speeches, relaying his blustering ego with hints of a paterfamilias’ wounded exhaustion. The character’s natural place exists on the stage, where his dialogue can be shouted into the modern parterre. During the play’s 2010 revival on Broadway, Denzel Washington used his sizable bombastitude to bring Troy to life. Six years later, the actor returns to the role and also directs the adaptation, which the playwright penned before his death in 2005.

Washington’s already larger-than-life screen presence gets even bigger as Troy, whose uninterrupted talk reveals his complicated life through stories and remembrances. Troy’s monologs and tirades about missed opportunities and his self-sacrificial toiling to preserve his household eventually reveal themselves to be filled with hypocrisy. Listening to Troy are his close friend Bono (Stephen Henderson), who’s always just about to head home, and Troy’s devoted wife Rose (Viola Davis, superb), who has set aside her own life to support her husband and their family. Forced to endure Troy’s remarks are his sons, whom he belittles with every word. In his thirties, the musician Lyons (Russell Hornsby) comes from an earlier marriage and cannot convince his father to listen to his music, even once; meanwhile, the teenaged Cory (Jovan Adepo) loses out on a chance to play college football because of his father’s ego. Troy’s brother Gabriel (Mykelti Williamson), a veteran brain-damaged in World War II, also arrives to interrupt various scenes, his presence a reminder of Troy’s selfishness.

Fences takes place before the Jim Crow laws were abolished and before the Voting Rights Act of 1965, but also in a time of rampant change when the Civil Rights Movement would begin to pick up momentum. Someone like Troy—with his punishing Southern upbringing, time in jail, brief stint as a Negro League baseball player, illiteracy, and hard work ethic as a sanitation worker—who remains unwilling to change with the world, becomes a tragic and often pathetic figure. Washington’s performance remains a work of genius, rendering Troy’s complexities, cruelty, and shortsightedness in all their aggressive immediacy. Less successful are the material’s attempts to exalt Troy in the finale, no matter how fondly he’s remembered by Rose or how much he’s influenced the lives of his children. However, in the subtext, and from a historical perspective, Troy stands as a product of his time and a sad reminder of the pre-Civil Rights era (not that it’s gotten much better in the decades since). Nevertheless, as a human being, Troy is also the kind of bastard that seems tolerable only on the American stage.

Indeed, Troy’s awful behavior throughout the film receives an absolute and unlikely sunshine-through-the-clouds forgiveness in the end, sappily created with computer-generated rays that put an artificial touch onto an otherwise authentic dramatic experience. Although the play was staged mostly in the Maxson house and backyard in Pittsburgh’s Hill District, Washington finds forced reasons to move the action elsewhere: in a bar, on Troy’s garbage route, outside of his sanitation post, etc. These moments seem less essential to the story than essential to Washington’s presentation of the story on film, creating visual variation for variety’s sake. Cinematographer Charlotte Bruus Christensen maintains a prominence of medium shots, resisting close-ups with only a few exceptions, but Fences never becomes a profound visual experience to match its drama.

Watching the film is about savoring the performances and listening to Wilson’s often punishing dialogue, which reveals internalized emotions through outbursts and confrontations. And while the stage offers an up-close-and-personal view of Troy Maxson’s life, the filmic presentation creates a distance between the characters and audience that Washington does not entirely overcome. Washington’s third turn as director (after Antwone Fisher and The Great Debaters), Fences does not make great cinema, even though it makes profound drama. It’s impossible to watch and not be moved. The performances, particularly those of Washington, Davis, and Adepo, radiate from the screen and have a lived-in quality—especially given that Washington and Davis are reprising their Broadway roles here. Painful and honest, Fences remains vital for its writing and acting, but the audience will never forget they are watching a play-to-film adaptation.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review