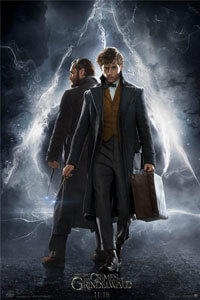

Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald

By Brian Eggert |

A second broom ride into J.K. Rowling’s Fantastic Beasts cinematic universe, The Crimes of Grindelwald interrupts its tedium with a few narrative standouts: an allusion to a homosexual relationship involving a beloved character from the Potterverse, a strain of anti-authoritarianism embedded into the plot, and at least two deaths of shockingly young innocents. Without these momentary diversions in the otherwise banal events, the Warner Bros. tentpole would be forgettable, much like its predecessor. Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them arrived in 2016 and, in its utter forgettability, seemed to make no perceptible impact on culture, pop or otherwise. Part two in a planned fiver under the newly christened “Wizarding World” cinematic universe—a title that awkwardly shimmers on the opening credits—The Crimes of Grindelwald is, for the moment, somewhat edgier and more potent than its predecessor, which is like comparing brands of white bread. From the digital monotony of its visuals to the uninvolving characters, it fails to evoke much of a response, aside from the occasional aww from a cute CGI beast.

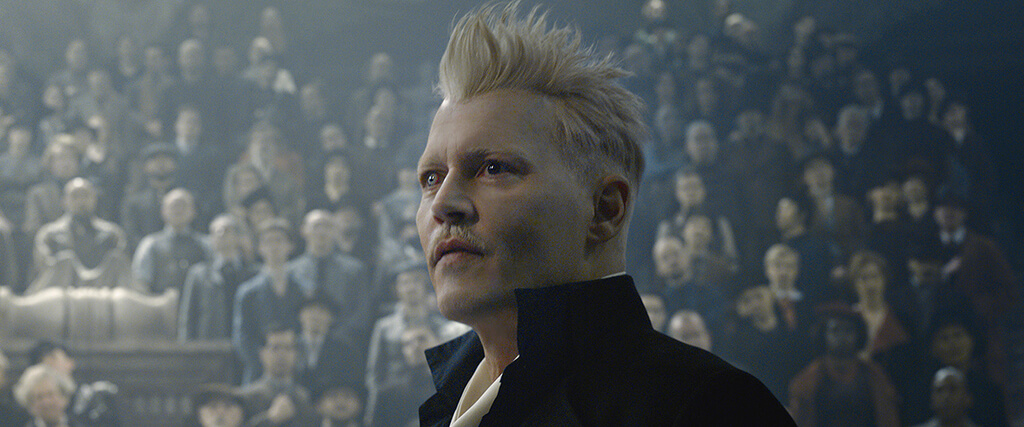

Less adorable is Fantastic Beasts’ hero, Newt Scamander (Eddie Redmayne), the awkward magizoologist who spends his time caring for a number of weird and wonderful creatures: A carryover from the previous entry, the enjoyable platypus-faced Nifflers scamper about, trying not to be noticed, albeit badly, as they stuff riches into their bottomless stomach sacks. There’s also the Bowtruckle, a personified stick-leaf that picks locks and steals buttons. The standout is the fearsome Zouwu, a large cat with massive fangs that moves like a Chinese dragon puppet in a parade, and yet, hilariously, it can be subdued with a silly cat toy found at your local pet shop. These are the most memorable characters from The Crimes of Grindelwald, not the dull wizards, witches, and muggles entrenched in another conspiracy involving a mythic Evil One and those trying to prevent his rise. In this case, everyone’s trying to locate Gellert Grindelwald (Johnny Depp), an evildoer who looks like Jack Frost with a parrot-coif; he wants to put the magically endowed at the top of Earth’s food chain, turning everyone else into veritable slaves.

The script, written for the screen by Rowling, once again feels bisected between two opposing elements that don’t fit within the same film. On the one hand, there’s Newt, a mumbling and antisocial weirdo whose interactions with computer-generated monsters seem important only to the Warner Bros. promotional department’s ability to sell stuffed Nifflers. Most scenes involving Newt feel removed from the central plot, set in 1927, even though he’s tasked by a young Dumbledore (Jude Law, ridiculously charming) to capture Grindelwald early in the proceedings. In the opening scenes, Grindelwald escapes from prison in an exciting, flying stagecoach sequence. He’s wreaking havoc in Paris, searching for Credence Barebone (Ezra Miller), a young orphan with untold dark magic abilities who’s teamed with a shape-shifting serpent-lady, Nagini (Claudia Kim). Why doesn’t Dumbledore just go after Grindelwald himself, you might ask? “It has to be you,” explains the Hogwarts instructor to Newt. But that doesn’t explain anything, does it? Later, we learn that long ago Dumbledore and Grindelwald took a blood oath to never fight one another, but that still doesn’t explain why Newt of all people must be our hero. Certainly, there’s someone, anyone more charismatic in the Wizarding World to fight the battle against the dark arts.

On the periphery, a dozen or so filler characters supplement Newt’s inadequacies as a protagonist, and in the process, carry the plot along. Newt’s company man brother Theseus (Callum Turner) works for the British Ministry of Magic as an Auror—the magic world’s FBI agent—the same occupation of the U.S.-based Tina Goldstein (Katherine Waterston), whom Newt fancies. Tina arrives in Paris to locate Credence, then Grindelwald, but she’s avoiding Newt due to a misreported announcement that he’s marrying Leta Lestrange (Zoe Kravitz), which he is not. Tina’s telepathic sister Queenie (Alison Sudol) also arrives in Paris from New York with her muggle fiancé, the comic relief Jacob Kowalski (Dan Fogler), who conveniently has total recall, despite his memory being wiped at the end of Fantastic Beasts. Somehow, the fate of Credence has something to do with Leta and her family history, inciting several muddled flashbacks. There’s enough plot here to fill a 600-page novel, and Rowling hasn’t mastered the art of cinematic shorthand, which screenwriter Steve Kloves applied so adeptly to the Harry Potter books in his screen adaptations.

On the periphery, a dozen or so filler characters supplement Newt’s inadequacies as a protagonist, and in the process, carry the plot along. Newt’s company man brother Theseus (Callum Turner) works for the British Ministry of Magic as an Auror—the magic world’s FBI agent—the same occupation of the U.S.-based Tina Goldstein (Katherine Waterston), whom Newt fancies. Tina arrives in Paris to locate Credence, then Grindelwald, but she’s avoiding Newt due to a misreported announcement that he’s marrying Leta Lestrange (Zoe Kravitz), which he is not. Tina’s telepathic sister Queenie (Alison Sudol) also arrives in Paris from New York with her muggle fiancé, the comic relief Jacob Kowalski (Dan Fogler), who conveniently has total recall, despite his memory being wiped at the end of Fantastic Beasts. Somehow, the fate of Credence has something to do with Leta and her family history, inciting several muddled flashbacks. There’s enough plot here to fill a 600-page novel, and Rowling hasn’t mastered the art of cinematic shorthand, which screenwriter Steve Kloves applied so adeptly to the Harry Potter books in his screen adaptations.

This time around, Rowling incorporates numerous references to the Potterverse that fans will recognize, seemingly in an attempt to connect, and thus render imperative, the less successful Fantastic Beasts storyline to the more popular Harry Potter films. In addition to Dumbledore and a brief glimpse of Professor McGonagall, Nicolas Flamel (Brontis Jodorowsky) appears alongside the Sorcerer’s Stone, while the presence of Hogwarts only serves to evoke nostalgia for the earlier movies. Rather than having an essential place in the rich tapestry of Rowling’s Wizarding World, such inclusions feel like Easter Eggs designed to incite fan buzz. It’s odd how Rowling has written a story that plays like fan fiction to a series she authored. One assumes that, by the end of the Fantastic Beasts films, Rowling will connect the material to the Harry Potter stories by ending at the beginning—perhaps by making the young Voldemort a character in later sequels, and then exploring his fateful attempt to kill the young Harry Potter.

In any case, director David Yates, helmer of the last several Harry Potter entries, delivers a shrug-worthy if competent blockbuster that’s missing the qualities that made the earlier films feel like lived-in environments inhabited by characters we love. The digital sheen of everything onscreen is occasionally disrupted by a memorable visual—a touch of blue flame; the magic world’s underground French circus; or Grindelwald’s way of calling a meeting in Paris with enormous, sheet-like clouds that appear overhead, blanketing the city in an ominous sheath. Philippe Rousselot’s cinematography, when confined to a soundstage interior or real-life city street, is atmospheric, desaturated to evoke a 1920s appearance, yet boosted by the presence of Colleen Atwood’s costumes. Most of the cast, especially Waterson and Law, are underutilized. At the very least, Rowling’s screenplay takes some bold steps in heightening the tension beyond its predecessor, introducing a villain with shades of Adolf Hitler (Grindelwald settles in Austria) and a certain modern-day counterpart—a character full of hatred for anyone he deems inferior, who will say anything to convince someone to join his side, regardless of how hypocritical that statement may be to the actions that follow. If only Rowling’s outspoken views and willingness to introduce mature themes into her now-firmly PG-13 universe could have been contained in a better film.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review