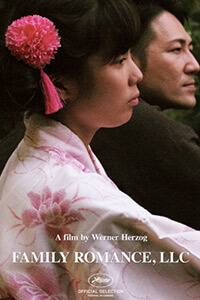

Family Romance, LLC

By Brian Eggert |

Werner Herzog is responsible for some of the most fascinating films of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. But whether he’s making fiction or non-fiction, the German director often finds his outsider subjects displaced in a world not their own, which accentuates both worlds—the one belonging to the outsider, and the one explored by the outsider. This is true of Grizzly Man (2005), about a Nature observer who lives among bears in the Alaskan wilderness; the Antarctic scientists in Encounters at the End of the World (2007); and the death row inmates of Into the Abyss (2011). But then, this is true of his fictional work as well, which includes Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972) and Fitzcarraldo (1982), films that commit so much to the Peruvian jungle experience that they defy the boundaries between reality and drama. To be sure, Herzog often raises questions about what’s real and what isn’t, making his documentaries look like fiction, and his fiction look like documentaries. With that in mind, Family Romance, LLC looks and feels like one of the German director’s many documentaries about humanity’s discomfited role in the modern world, except it’s fiction. Sort of.

Shot on a small handheld digital camera operated by Herzog himself, the film features unprofessional actors giving sometimes awkward, unpolished performances. They look and behave like documentary subjects. But the screenplay of this fictional feature based on real-life, credited to Herzog, consists of mostly improvised scenes, suggested from a story by Roc Morin, a student from Herzog’s Rogue Film School. It concerns Japan’s so-called rent-a-family industry, a subject recently featured everywhere from Conan O’Brien’s late-night show to Elif Batuman’s 2018 article in The New Yorker. Several agencies in Japan specialize in renting out actors who play family members for their clientele. The service is designed to fill some gap in its clients’ lives. In some cases, it’s used to combat the chronic loneliness currently infecting Japanese society; others use it to supply stand-ins for their somehow absent, ineffectual relatives. What fascinates Herzog is how something artificial produces a genuine emotion.

The film stars Yuichi Ishii, the founder of a real-life Tokyo-based company called Family Romance (Herzog added the “LLC” to his title for effect). While researching the subject of rental relatives, Herzog met Ishii and asked him to play the lead role, a version of himself. In the screen story, Ishii has been hired as the 12-year-old Mahiro’s long-absent father, in hopes that his presence might help Mahiro overcome her abandonment issues. The rental father and the adolescent girl meet in the opening scene on a busy bridge, where Herzog watches their staged reunion unfold with fly-on-the-wall distance. Pedestrians, unaware that Herzog is filming them, pass by the camera and take no notice. Much of the film carries on this way, with Ishii and Mahiro meeting in public, while Herzog’s observational camera watches them interact in an open-air space. We also follow Ishii on other assignments: One woman needs a rental to replace her husband, whom she claims is epileptic, for her daughter’s wedding ceremony; another woman wants to relive the moment she won the lottery; another still wants to engineer her social profile to go viral, so she hires fake paparazzi.

Creating a fictional scenario out of a real-life phenomenon, Herzog tests the boundaries of documentary and dramatic filmmaking, resulting in a strange crossbreed that resembles the director’s The Wild Blue Yonder (2005)—a work of science-fiction in which Herzog interviews an alien (Brad Dourif) about humanity’s destruction of Earth. But then, the German maverick has always taken liberties with reality to find the poetic truth at its core; it’s the persistent theme of his work. At times, he seems preoccupied with the melodramatic possibilities of his story, offering heavy-handed scenes of Ishii weighing the implications of his profession. Near the end, Ishii wonders if his own loved ones are actors just playing roles. But by merely watching and allowing his camera to linger much longer than another director would, Herzog invites questions about the social roles we play and the nature of reality itself. Watch his long, ponderous shots inside one of Japan’s robot hotels, where the concierge is a rubber-faced automaton and the fish tank contains swimming robots. Ishii asks the human manager a Herzogian question, whether or not the androids dream. What kind of truth do these artificial characters have, and how is that different than a human being hired to give the same greeting to the hotel’s guests?

Family Romance, LLC debuted at the Cannes Film Festival in 2019, and some critics were convinced that it was a documentary. Certainly, it’s evident that Herzog uses footage that he captured on the streets of Tokyo (he even enters a hedgehog bar), apparently without the necessary permits. When his roving, handheld camera isn’t probing his characters in intimate close-ups, Herzog employs drone imagery that watches Tokyo’s Yoyogi Park and its blooming cherry blossoms from a bird’s eye view. However real many of the film’s images may be, reality is an elusive prospect here, wrapped in layers of lies and self-deception. It’s about people who knowingly interact with paid actors, who are played by paid actors, who in reality work for Ishii’s company—and yet somehow, Herzog finds genuine emotion through the metatextual web. “Sometimes we are all invisible,” says Ishii at one point. It’s a remark that brings to mind any number of Herzog’s subjects over the years—people who operate on the margins and yearn for some measure of connectivity. Fringe though the material may seem, Family Romance, LLC reveals a familiar condition of social isolation that feels achingly relatable.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review