False Positive

By Brian Eggert |

False Positive opens with a woman, her face and shirt covered in blood, plodding down the street as though coming from trauma and walking toward a light. With this moment, set to kaleidoscopic music from a Tim Burton reverie, the movie signals its use of horror and fantasy to comment on real life. Director John Lee, who co-wrote the screenplay with his star, Ilana Glazer, confronts the reality of millions of women who undergo fertilization treatments to become pregnant. It’s an uncomfortable, desperate, and painful process filled with self-doubt and anxiety. The process is inherently weird, too, like something out of science fiction. Doctors extract elements of the body and combine them in a lab, or sometimes right in the body, to ensure a pregnancy. However invasive and awkward, assisted reproductive technology is the only option for many couples. And since the process is usually met with much uncertainty and discomfort, it’s the perfect arena for a horror movie.

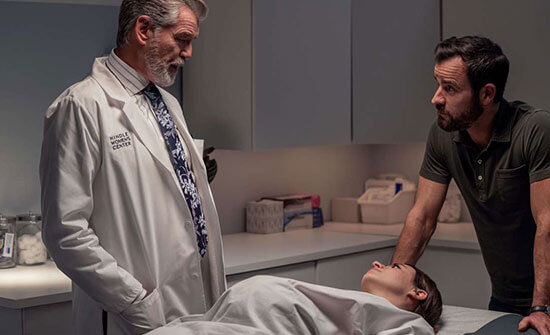

Glazer stars as Lucy, a woman who wants it all. She’s married to a reconstructive surgeon, Adrian (Justin Theroux), who loves his Peloton almost as much as his wife. They have a posh apartment in Manhattan, where Lucy is a marketing maven and recently landed the lead on a valuable new account for her agency. Still, she dreams of more—having a baby. They have been trying for years yet remain unable to conceive. The screenplay touches on Lucy’s sense of failure. “As a woman,” she says, “this is the one thing I’m supposed to be able to do, and I can’t do it.” Fortunately, Adrian arranges for his mentor, Dr. Hindle (Pierce Brosnan), one of the world’s foremost fertility experts, to help them with his experimental blend of intrauterine insemination and in vitro fertilization. Inside the antiseptic doctor’s office, Hindle eerily reassures her, “You are in good, and hopefully, warm hands.” Creepy, dude.

Poked, prodded, examined, and retracted in Dr. Hindle’s office, Lucy becomes pregnant, and then some. Dr. Hindle’s procedure creates not one but three babies. To ensure a healthy pregnancy and birth, Lucy has a choice to make: she can keep the two twin boys or the single girl. Whichever one she decides to keep, the others will be removed by selective reduction. But Lucy wants a baby girl so badly that she ignores the warning signs: The casual references to Hindle’s god complex (“Sometimes I wish I could clone myself”). The way Hindle reassures Lucy when she worries about making the wrong choice (“I won’t let that happen”). The chumminess between Adrian and Dr. Hindle. The way Adrian wants to keep the boys, insisting that “we’re pregnant” and it’s “our decision.”

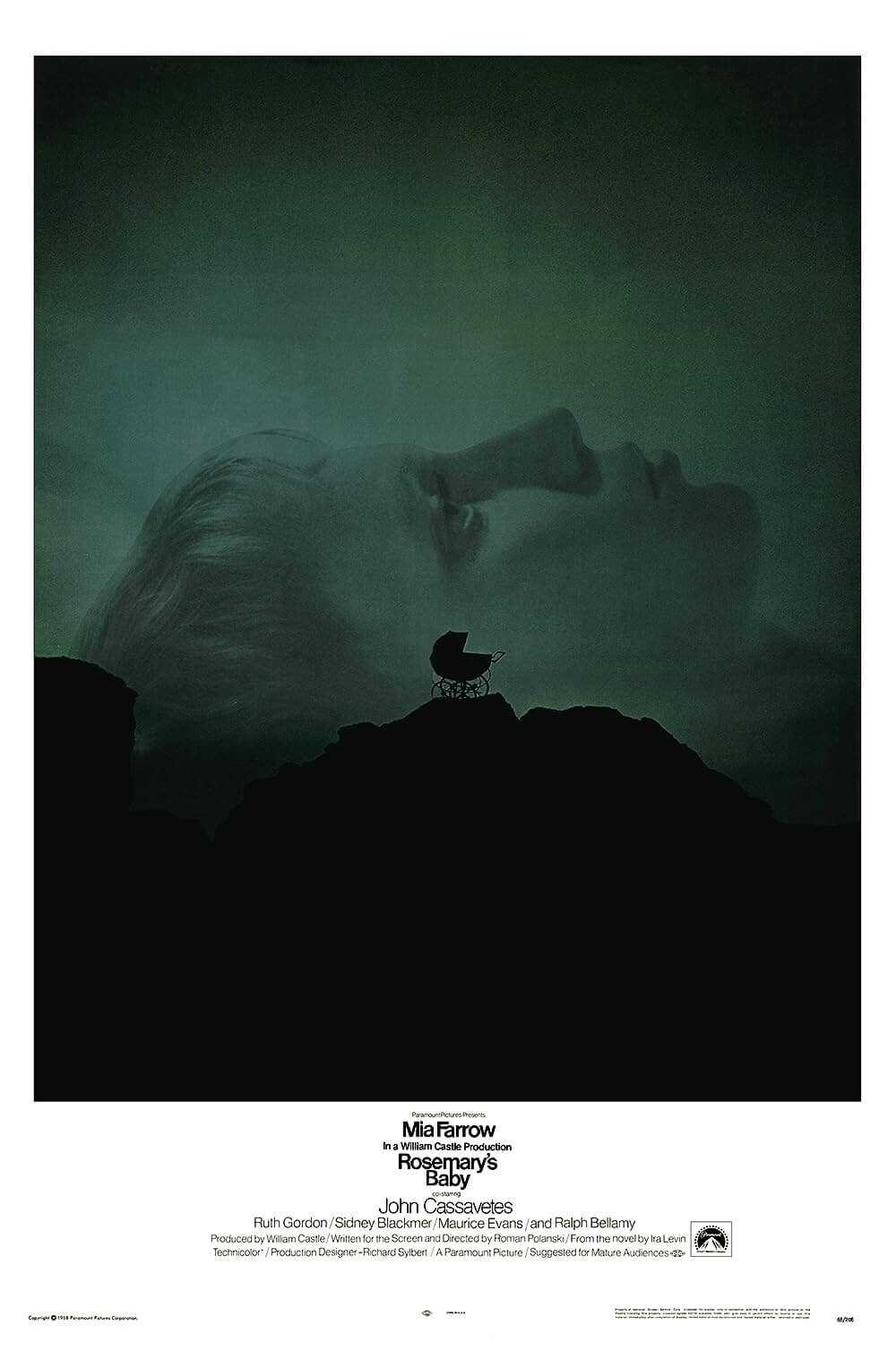

False Positive fits nicely into the pregnancy horror subgenre, which is so triggering for some viewers that Hulu added a disclaimer before the movie. Titles such as The Unborn (1991), Grace (2009), Prevenge (2011), and others conceive of nightmare scenarios, usually based on women’s real-life anxieties and experiences. Unfortunately, Lee and Glazer don’t attempt to hide their inspirations, making the film into a thinly veiled modern update of the mother of all pregnancy horror movies, Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby (1968). So we get familiar scenes: Lucy, half-conscious, hears others scheming; she feels paranoid, convinced that something is wrong with her baby; her husband suddenly doesn’t take her side; and she’s gaslighted by others, who cover up their very real conspiracy by claiming she’s unable to make decisions about her own body. Again, it’s all familiar stuff, although it leads to a novel climax that resists the whole Satanist angle. But the movie’s sharp observations about modern baby culture earn False Positive a pass for its many derivations.

False Positive fits nicely into the pregnancy horror subgenre, which is so triggering for some viewers that Hulu added a disclaimer before the movie. Titles such as The Unborn (1991), Grace (2009), Prevenge (2011), and others conceive of nightmare scenarios, usually based on women’s real-life anxieties and experiences. Unfortunately, Lee and Glazer don’t attempt to hide their inspirations, making the film into a thinly veiled modern update of the mother of all pregnancy horror movies, Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby (1968). So we get familiar scenes: Lucy, half-conscious, hears others scheming; she feels paranoid, convinced that something is wrong with her baby; her husband suddenly doesn’t take her side; and she’s gaslighted by others, who cover up their very real conspiracy by claiming she’s unable to make decisions about her own body. Again, it’s all familiar stuff, although it leads to a novel climax that resists the whole Satanist angle. But the movie’s sharp observations about modern baby culture earn False Positive a pass for its many derivations.

Lee and Glazer’s script follows the oddly humorous tone set in Polanski’s film, which uses believable characters in haunting situations. As a result, False Positive has an air of comic absurdity when portraying the people in Lucy’s life. Note how Lucy’s boss touches her on the back or knee, asks her to order lunch, and tells her, “you’re glowing.” Or the pregnancy group where Lucy and snobbishly self-satisfied mothers-to-be talk about “mommy brain.” And then there’s Adrian, who, a little too perfect and understanding, has some dark secrets. These characterizations reveal a satire beneath the horror surface, contained in the dialogue and how the actors perform their lines. If you watch the movie and then watch it again, knowing what eventually happens, the quotes I’ve already mentioned become obvious and playfully schlocky clues of things to come.

Just as in Polanski’s film, the viewer begins to doubt the protagonist, but Lee gives us greater reason to question Lucy’s sanity. For one, she’s obsessed with Peter Pan imagery, dreams of naming her daughter Lucy, and more than once seems to drift off to Neverland. She’s prone to fantasies about motherhood, and she’s disturbed when they don’t meet her expectations. A subplot involving a Black midwife “with soul” (Zainab Jah) reveals that Lucy has dreamt up a tribal stereotype to counteract her anxieties about Dr. Hindle’s laboratory-like clinic. It’s shot at times like a waking dream or nightmare. Cinematographer Pawel Pogorzelski uses the same clarity and terrible beauty he brought to Hereditary (2018) and Midsommar (2019) for Ari Aster, capturing the doctor’s office with unnerving cleanliness. And there’s no element more uncanny and disturbing than Hindle’s nurse Dawn (Gretchen Mol), an unwavering drone who smiles with menace and jealous devotion to her employer. And it all seems exaggerated by Lucy’s perspective.

When False Positive finally turns into a real bloody horror show, Lee and his editor Jon Philpot don’t dwell on the violence or gore. Instead, they introduce traumatizing imagery and cut according to Lucy’s fractured mental state. Their concern is Lucy’s point-of-view, portraying the dizzying uncertainty that first-time mothers experience from a place of truth, while building toward a jagged and devastating climax. But, admittedly, the ending feels rushed and unsatisfying. Even so, Glazer, best known for the sitcom Broad City, where she collaborated with Lee, gives a convincing performance that reveals Lucy as intelligent yet somewhat naive in her optimism. She plays subtle moments of tension between Lucy and Adrian with the same skill as the intense confrontations late in the movie. What works best is how Glazer and Lee make the proceedings just familiar enough to be relatable, while also making the story’s transition into horror freakily memorable.

(Note: This review was suggested by supporters on Patreon.)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review