Experimenter

By Brian Eggert |

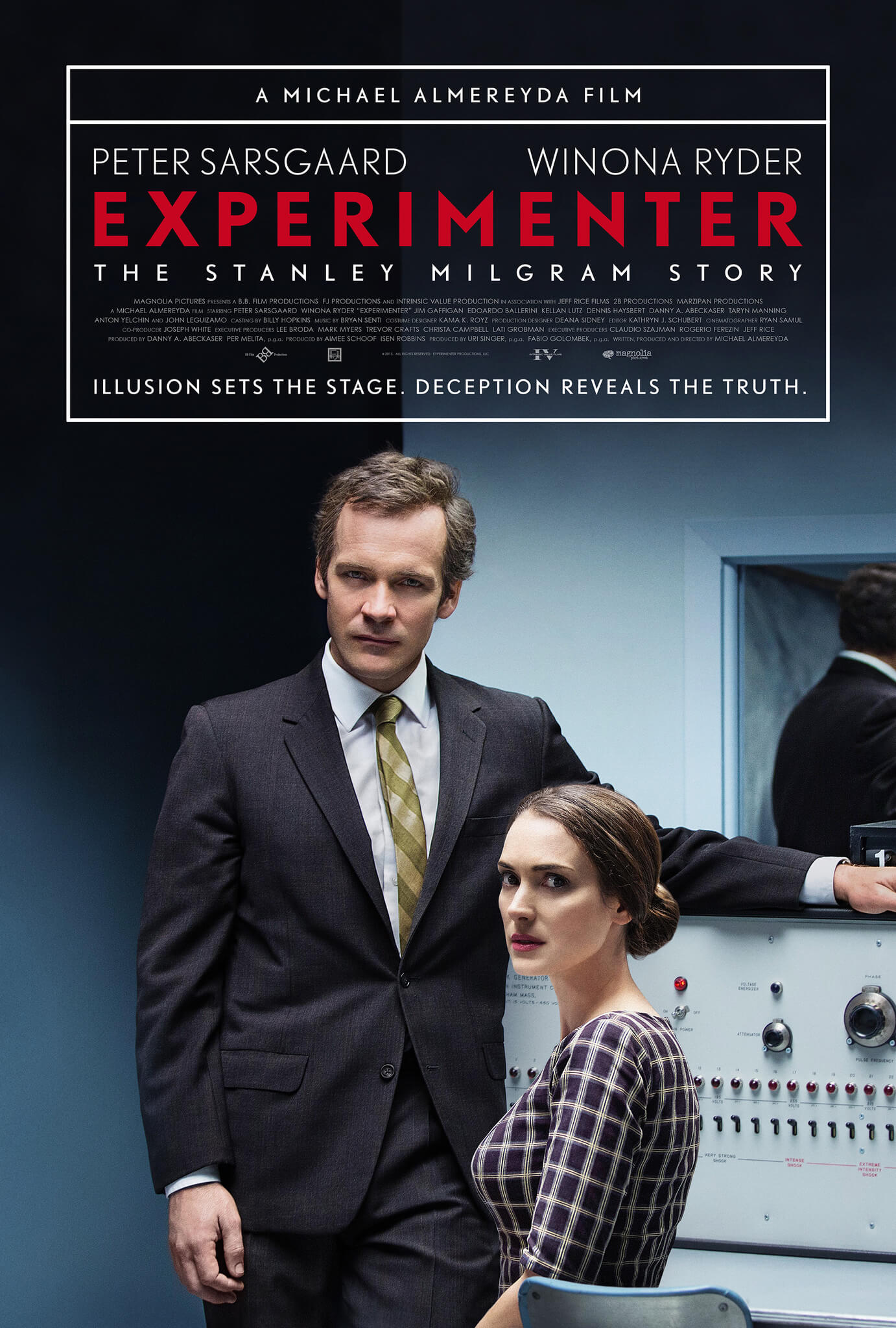

Anything less than an unconventional biography of Stanley Milgram and his divisive obedience experiments would betray the subject matter. Michael Almereyda’s film Experimenter considers the significant discoveries found in Milgram’s “Obedience to Authority” study, which made Milgram a popular topic in Psychology 101 courses and beyond when discussing the ethics of his approach. Writing, producing, and directing, Almereyda realizes his first feature-length effort since his modern-day adaptation of Hamlet in 2000. Though the story of Experimenter touches on major events in Milgram’s life, played with a Machiavellian glint in his eye by Peter Sarsgaard, the formally unusual picture concentrates less on Milgram himself than the thematic epicenter of his work. Milgram suggested that the vast majority of humanity willingly complies with perceived figures of authority, to such an extent that they’re willing to torture others to remain complicit, a message often lost during heated debates about Milgram’s arguably unethical scientific methods.

Watching his experiments through a two-way mirror, a silent observer not unlike a moviegoer, Milgram watches the scene unfold: Two volunteer test subjects assigned to separate roles of “Teacher” and “Learner” enter neighboring rooms, the Teacher seated at a desk in front of a control panel, the Learner on the other side of a wall and strapped to electrodes. Milgram’s staff tells them that the Teacher must ask a series of questions, and the Learner must respond. With each wrong answer, the Teacher must deliver an increasingly powerful electric shock to the Learner. And while the Teacher has felt the lowest level of electrical shock as an example of the pain he will be inflicting, the planted Learner (Jim Gaffigan) actually receives no shocks whatsoever; the experiment is all about whether the Teacher (played by various actors, including Anthony Edwards, John Leguizamo, Anton Yelchin, etc.) will deliver what he believes are shocks because, according to what Milgram’s staff tells them, the authority in the room, that it’s what they’re supposed to do. Never mind if the Learner pleads for the shocks to stop on the other end—few Teachers mind at all, and instead continue to administer punishment, despite displaying visible signs that they don’t want to be participating.

Milgram was Jewish, born in America, and of Romanian-Hungarian decent. He had good reason to want to explain the origin of genocide, his parents having survived World War II, and having been appalled by other atrocities that took place during his life (1933-1984). Alongside his wife (Winona Ryder), whom he meets in a common social situation on an elevator, Milgram proceeds to conduct his obedience experiments on upwards of 800 subjects and publishes a book on his findings in 1974. He conducts other experiments, of course; for one, he coined the term “six degrees of separation” with a clever study involving a package that was passed along between people on a first-name basis with one another and, in the end, suggests everyone in this Small World is connected. As Almereyda looks at Milgram’s work, we begin to observe Milgram’s awareness of his own susceptibility to human social conventions, his acknowledgment that his research may not change human nature, and meanwhile his careful control of every situation—the pleasure he takes from being the master of his behavior experiments.

To be sure, a large portion of the human race receives pleasure from power, whether they like it or not. Watch Craig Zobel’s 2012 film Compliance, based on a true story of a store clerk who put a fellow employee through a degrading strip search because someone claiming to be a police officer on the phone told her to. It’s a disturbing little movie that shows the extent some are willing to go to remain complicit with authority. As we see in Experimenter, Milgram borrowed several of his ideas from episodes of the popular TV show Candid Camera, where people are placed in awkward situations and go against their better judgment to conform to comedic effect. Milgram is less accepting of the 1976 made-for-TV movie called The Tenth Level, in which William Shatner plays him in a cheap assessment of his work. Almereyda includes references like these to show how Milgram’s research became somewhat popular; but he also includes scenes where Milgram is stopped on the street and insulted because people who don’t understand what he’s trying to do read a bad review of his book.

At the same time, Almereyda chooses unique formal techniques that underscore the social artifices in our lives, just as Milgram’s research did. Production designer Deana Sidney uses black-and-white rear-projected backdrops (a common practice for the 1940s and 1950s cinema, and sometimes used as an intentionally stylistic flourish today, like the driving scenes in Pulp Fiction) for scenes of marital dialogue in the car and significant social meetings, such as when Milgram dines with his mentor—all moments where Milgram openly adopts an acknowledged “role” (the husband, the mentee, etc.). On other occasions, Sarsgaard looks straight at the camera and speaks to the audience, as if Milgram is the host of his own life. Or he walks down a Yale hallway, followed by a proverbial (and quite literal) elephant in the room, played by a full-size animal. Milgram’s studies tried to emphasize the elephant in the room in all social situations, and Almereyda chooses creative ways to depict them and reinforce his subject’s role in the world around them.

Just like Milgram’s obedience experiments, Almereyda’s film will undoubtedly be a conversation starter as to the ethical implications of Milgram’s approach. Almereyda surely remains sympathetic to the figure, and given the outcomes of his research, why not? Sure, Milgram pushed boundaries, but he also achieved irrefutable results—results a panel of other psychologists said would never be the case; they thought people would outright refuse to shock another person. They were frighteningly wrong. And while Experimenter does not overly concern itself with Milgram’s personal life and successes, the more human scenes are included as a way to reinforce why he approached certain subjects in his research. The film is a fascinating approach to its subject and unconventional compared to similarly themed titles like, say, Kinsey (2004). The result may leave some viewers emotionally cold toward the material, but our intellect is engaged in the engrossing subject and the absorbing way it was made.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review