Ex Machina

By Brian Eggert |

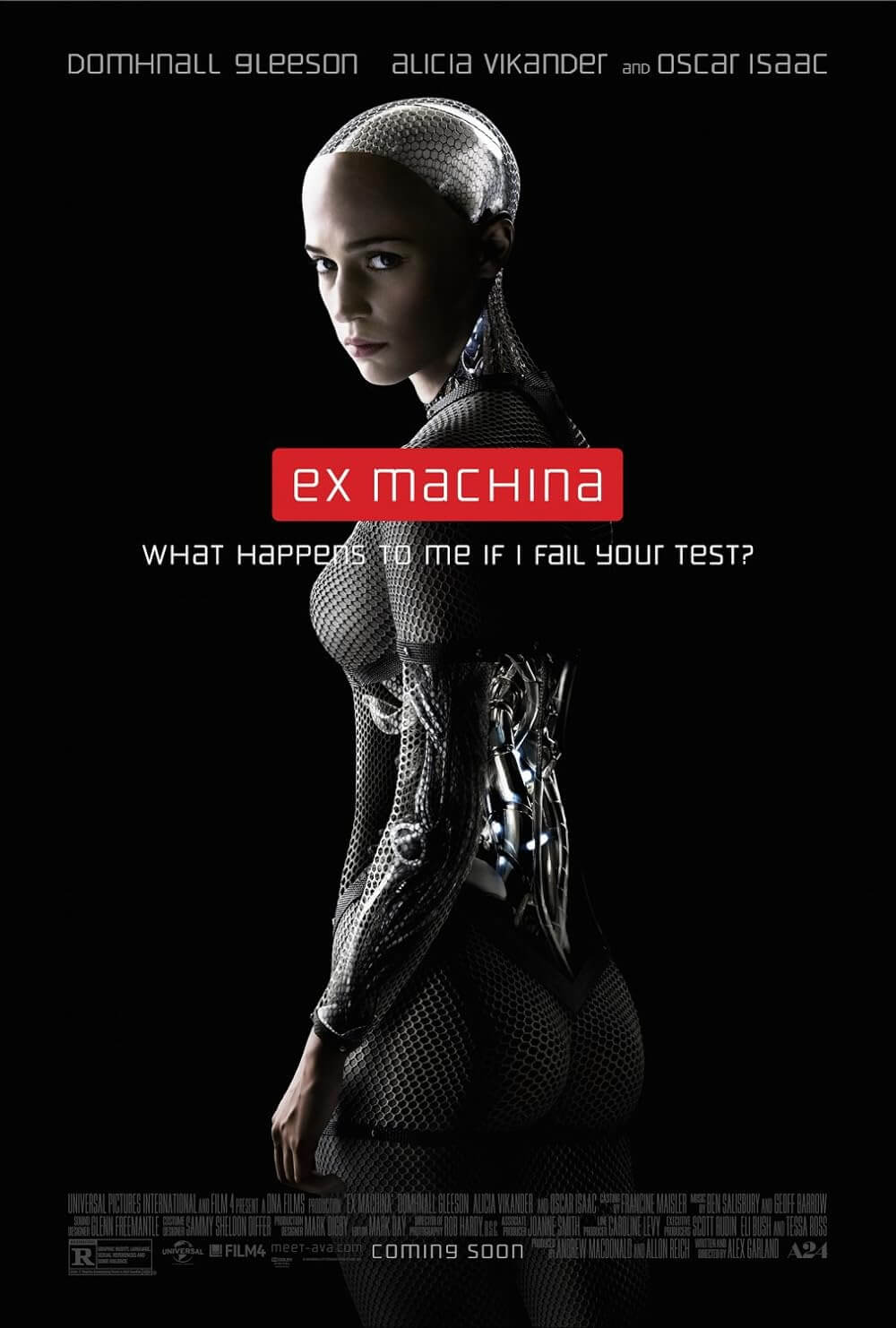

Imagine spending an intimate week with Steve Jobs at his prime, except a version of Jobs who gets drunk every night and disco dances with a mute Japanese assistant. And also, Jobs has created a thinking, feeling robot, and you’re the guinea pig who will determine if his creation is real enough. When he wins an office contest at his larger-than-Google search engine company called Blue Book, young programmer Caleb (Domnhall Gleeson) receives a Golden Ticket invitation to the secluded Alaskan compound of his virtuoso boss Nathan (Oscar Isaac). While overwhelmed by the experience of meeting Nathan and the possibility of securing his future, Caleb quickly learns that he wasn’t a lucky winner but, in fact, was chosen. Rather than picking Nathan’s brain for a week, Caleb will assist in a top-secret project to test the quality and believability of Nathan’s invention, the first artificially intelligent android, Ava (Alicia Vikander). Over the course of several sessions, Caleb must interact with Ava and subject her to a “Turing Test” that, not unlike the Voight-Kampff empathy test in Blade Runner (1982), will evaluate whether she is indistinguishable from a human.

Operating on the level of a tense stage play rather than a twisting science-fiction yarn, Ex Machina, the directorial debut of Alex Garland, contains cutting and highly technical dialogue over a thoughtful thematic philosophy—enough to require the same high-IQ, science-savvy audience that could watch Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar (2014) without looking up the basics of relativity on Wikipedia. The motives and manipulations of Garland’s three central characters become fascinating and ultimately unnerving, if not altogether haunting, through the course of his stylish freshman effort. Ex Machina was shot on a minimal budget of $13 million and released by independent distributor A24, which also put out Jonathan Glazer’s Under the Skin (2014), a film that similarly challenges its audience to identify with an alien. Steeped in influences ranging from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein to Karel Čapek’s breakthrough 1920 play R.U.R., Garland weighs concepts of artificial life and consciousness, yet he carefully avoids Isaac Asimov’s “Three Laws of Robotics”, which prevented robots from harming human beings, and therein creates an eerie tension.

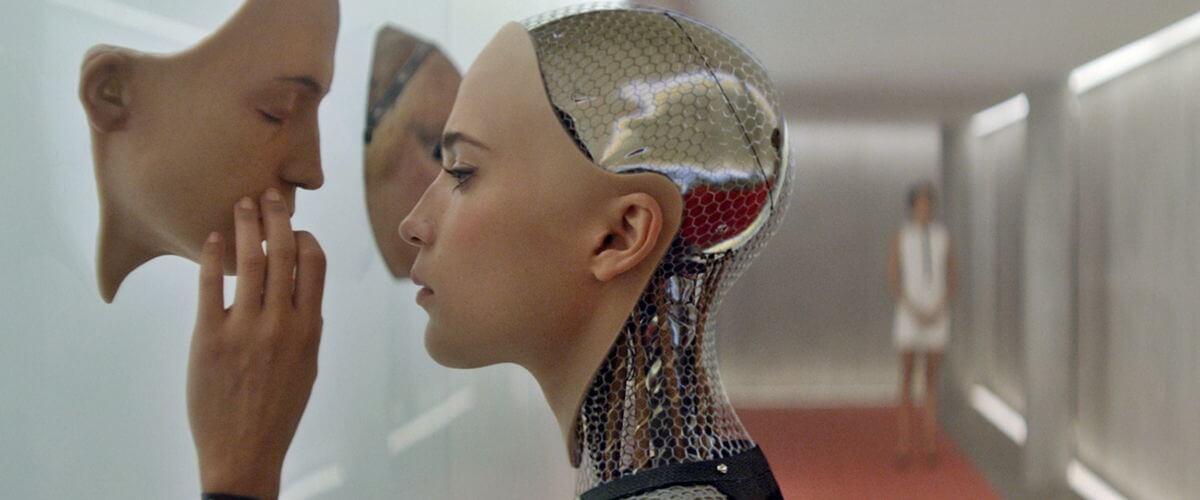

Normally conducted over keyboard communications, so the interrogator must judge the subject’s humanness based on the responses, Nathan’s version of the Turing Test is far more ambitious. Caleb must sit across from Ava in a secured room, a pane of unbreakable glass between them, and look at the robotic subject during his sessions. (But he avoids acknowledging the mark on the glass wall, where something hit it hard enough to crack it.) He studies her responses and deliberate movements, but the character’s humanity resides in her expressions and pretty human face, which gives way to a transparent cranium, midsection, and appendages that show her blue and humming internal workings. But Caleb’s questions to Ava are turned around on him, and, gradually, it becomes clear she’s controlling the conversation, using her personality and even sexuality to influence her interrogator. Just as Ava cleverly controls the testing, Nathan has almost complete authority over the testing environment and beyond. His compound has locked rooms that require a keycard to access; cameras capture every corner of every room, and the entire building runs on an independent power source, which fluctuates from time to time. And let’s not forget his assistant named Kyoko (Sonoya Mizuno), who seems destined to suffer Nathan’s boorish behavior.

Indeed, Nathan remains the most fascinating, bullying specimen in this three-pronged character study. From the moment Caleb arrives, he insists on beer and bromantics; he tries to convince his “contest winner” not to use his technical intellect, but rather his emotions to judge Ava. Nathan is also a moody, temperamental depressive, and offers Isaac quite a different role than his passive character in Inside Llewyn Davis (2013) or honorable businessman in A Most Violent Year (2014). Gleeson, from About Time (2013) and Frank (2014), is a far more reactive and quietly sympathetic creature, in such a way that the viewer even suspects he may be one of Nathan’s creations—until Garland dispels that idea in a disturbing scene. Meanwhile, Vikander’s performance is modulated, as intended. The Swedish former ballerina moves with deliberate, smooth precision, and with every expression, it’s evident she’s processing her situation, that she feels imprisoned by and mistrusting of Nathan. But not until the last few scenes does it become apparent that Ex Machina is less about Caleb’s attestation of Ava’s consciousness than her consciousness itself. Garland’s third act brilliantly and unexpectedly repositions the entire picture around her, and leaves the viewer wanting to watch the entire experience again with a focus on Ava.

Indeed, Nathan remains the most fascinating, bullying specimen in this three-pronged character study. From the moment Caleb arrives, he insists on beer and bromantics; he tries to convince his “contest winner” not to use his technical intellect, but rather his emotions to judge Ava. Nathan is also a moody, temperamental depressive, and offers Isaac quite a different role than his passive character in Inside Llewyn Davis (2013) or honorable businessman in A Most Violent Year (2014). Gleeson, from About Time (2013) and Frank (2014), is a far more reactive and quietly sympathetic creature, in such a way that the viewer even suspects he may be one of Nathan’s creations—until Garland dispels that idea in a disturbing scene. Meanwhile, Vikander’s performance is modulated, as intended. The Swedish former ballerina moves with deliberate, smooth precision, and with every expression, it’s evident she’s processing her situation, that she feels imprisoned by and mistrusting of Nathan. But not until the last few scenes does it become apparent that Ex Machina is less about Caleb’s attestation of Ava’s consciousness than her consciousness itself. Garland’s third act brilliantly and unexpectedly repositions the entire picture around her, and leaves the viewer wanting to watch the entire experience again with a focus on Ava.

Garland received his start working as a screenwriter for Danny Boyle, first in an adaptation of his book The Beach (2000), and then later genre-redefining efforts like the first fast-zombie film, 28 Days Later (2002), and the ruminating space mission Sunshine (2007). Along with other titles like Never Let Me Go (2010) and Dredd (2012), Garland has made a considerable impact on the sci-fi genre as a screenwriter. His first directorial effort proves his talent extends beyond the printed page. Ex Machina is a precisely shot and labored-over production that looks much more expensive than its price tag suggests. Garland brought along production designer Mark Digby, who worked on 28 Days Later as a supervising art director and designed the production of Dredd. Spare hallways and concrete walls convey an emptiness that is contrasted by the significant presence of a Jackson Pollack painting hanging on Nathan’s wall. Expert CGI brings Ava’s robotic internal machinery to life, while the entire film has a futuristic surface sheen, an almost glowing quality courtesy of the soft, often hued lighting by cinematographer Rob Hardy.

The expert technical package in Ex Machina never distracts from the film’s overall themes, however, which revolve around questions of humanity. What makes someone human, or sentient? And if you create artificial sentience, does it automatically have the same rights as a human? Audiences have been seriously asking these questions about intelligent androids since we were first introduced to Data on Star Trek: The Next Generation. Much like Data, Ava seems to have emotions and desires. She expresses herself through artwork, and she appears melancholy in her cage. And like any conscious intelligence, from a lion in a zoo to an imprisoned human being, if locked up they will want to escape. As Ex Machina progresses and Ava demonstrates her desire to be freed, questions about Ava and artificial lifeforms transfer over to questions about Nathan and humanity. How does anyone really know what someone else is thinking? How do we know that the expressions or responses conveyed by people haven’t been tailored to impart an intended response? Human beings are deceptive creatures. And if someone creates a truly conscious artificial being, wouldn’t the final test of its humanness be its ability to deceive based on its own desires? To be sure, Nathan’s capacity for dark secrets carries over to Ava and makes the last act of Ex Machina both disturbing and fascinating.

Ex Machina‘s characters and their increasingly tense interplay absorb the viewer on a level few films do, allowing the actors to deliver performances that feel lived in for much longer than the film’s runtime. Garland has achieved a picture that seeks answers about humanity, and what it finds is that our motives are often suspect and our behavior duplicitous, however well-intentioned we may seem. For example, the creator of artificial intelligence might grow jealous of its superior creation or have selfish motives for creating it in the first place. In its most reduced form, the film’s central theme is that pure intentions rarely exist in human beings, and therefore a true artificial intelligence will veil its yearnings like humans often do. In that sense, Ex Machina could be a precursor to Steven Spielberg’s A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001), where human beings find they have apprehensions, if not downright hatred for something that is smarter, lasts longer, and ultimately reflects humanity too well. By considering such ideas in an enclosed environment with so few characters, Garland has made Ex Machina an intense, engaging film that plays with the viewer’s head and, as the best films often do, demands an exceptional degree of time to process.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review