Event Horizon

By Brian Eggert |

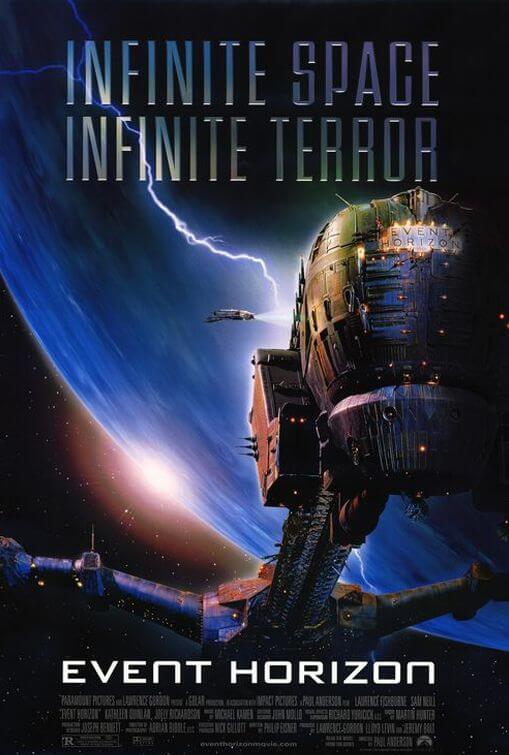

Amid his long list of Z-grade actioners and mindless videogame adaptations, Paul W.S. Anderson comes as close to making something great as he’s ever likely to with Event Horizon. If only he could get that whole story thing down. Having slowly earned minor cult status since its 1997 release, the film stands apart through the audacity of its gorific imagery and the potential of its psychological science fiction-horror concept. However, the muddled script threatens to upend the stunning sets and visuals on display. Though fondly remembered as it may be, neither nostalgia nor genre-bending fandom distracts from the formulaic plot structure or inane dialogue spoken by actors too good for the material. And in the end, Anderson proves only that he cares more about purveying senseless violence and exploring cult-worthy scenarios than directing a polished script.

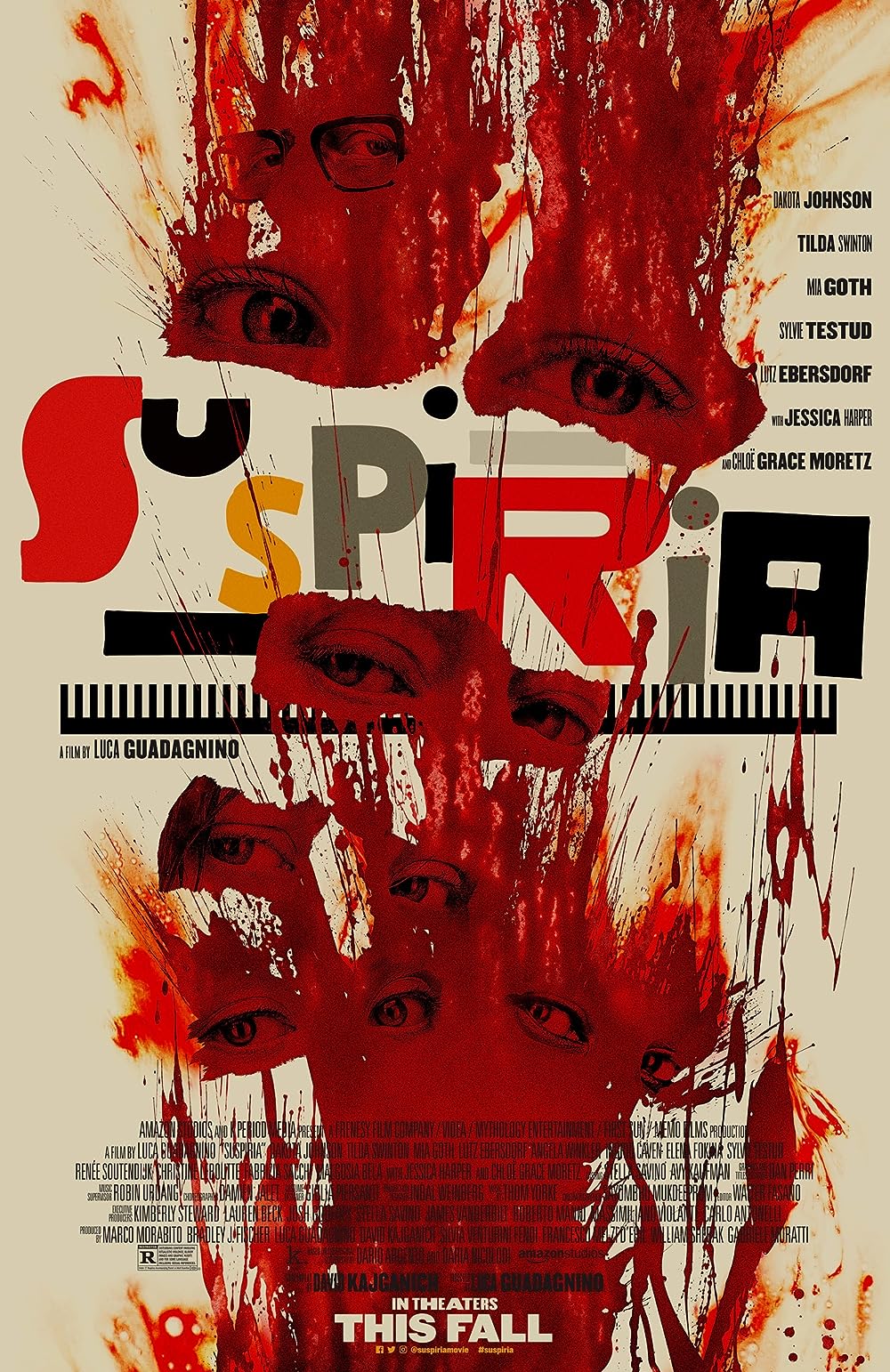

Some audiences don’t mind that the film’s ideas fail to live up to their possibility. They’re just pleased to see disturbing bloody violence in a familiar Alien-meets-Hellraiser situation, even if that means reducing the lofty potential to a mere And then there were none formula. You know the kind: Characters meet their doom one by one, sparking a mystery, until the cause is dramatically revealed in the finale. Leaving it to the audience to decide what’s more important, story or aesthetics, Anderson’s (eventual) commercial success here makes a strong argument that pure visual ingenuity triumphs over the need for, say, a plausible plot or tolerable dialogue. Then again, the genre-savvy viewer may have trouble accepting how thoroughly Anderson borrows from the well of science-fiction and horror movie tropes. Every scene is derivative of some classic: 2001: A Space Odyssey, The Black Hole, The Shining, Solaris—they’re all here. So it’s no wonder that the screenwriter, Philip Eisner, later wrote Mutant Chronicles.

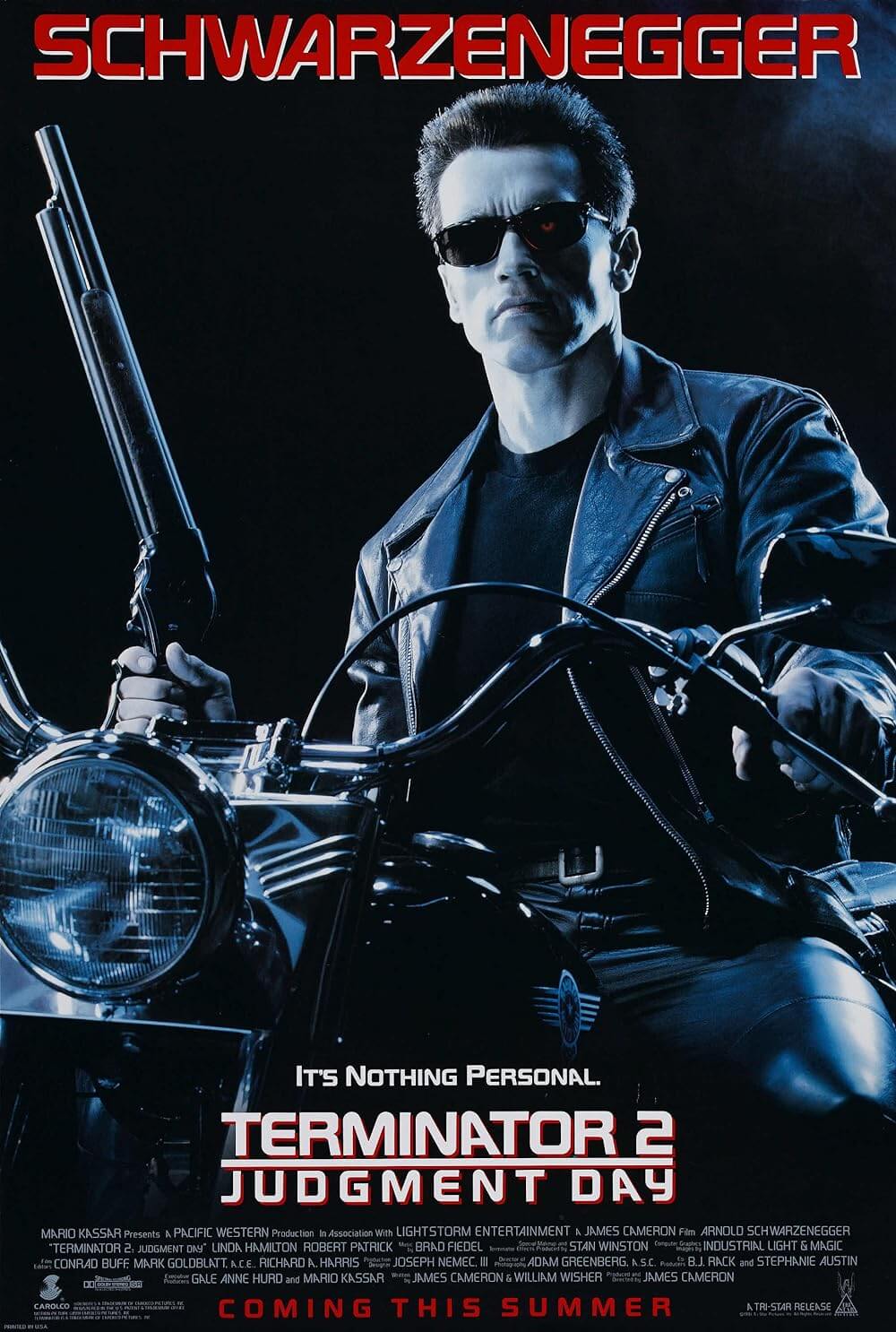

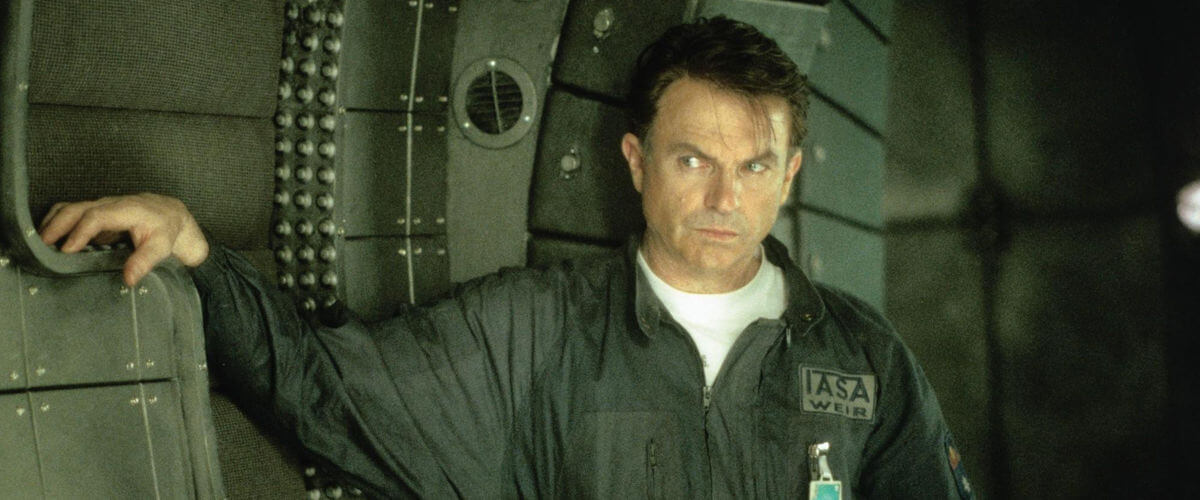

The story, set in 2047, involves a space rescue operation orbiting Neptune, where the lost vessel Event Horizon has miraculously reappeared after seven years. It vanished when it opened the first human-made wormhole and didn’t return from its destination. Where did it go? What happened to its crew? The roughneck team on the search-and-rescue craft Lewis and Clark voyage out to answer these questions. Its orderly Captain Miller (Lawrence Fishburne) barks commands, while its blue-collar crew chummily interacts in the way every space crew has since Alien. They’re accompanied by Dr. Weir (Sam Neil), the designer of the lost ship. He explains that his craft was made to “bend the universe” and punch a hole therein to instantly travel from Point A to Point B. When coming upon their destination, it’s apparent something terrible has happened to the previous crew. Bloody carnage covers a wall. Horrific video records suggest the crew went mad and slaughtered each other, but not before telling anyone listening to the log to “Save yourself from Hell!”

At the heart of the adrift ship resides the Gravity Drive, a whirling ball of lights and metal that opens up a portal to who-knows-where—cryptic messages from the former crew would suggest a Hell-like alternate dimension, but the movie never clarifies to the point of understanding. Suffice it to say that the returned vessel is now evil and somehow alive; it causes the Lewis and Clark crew to hallucinate about their various pasts. For some reason, Dr. Weir goes nutso and begins murdering his comrades. The panicky crew still has time for snarky comments, though. Flash weird and bloody images onscreen, cut to the eerie Gravity Drive for effect, input some techno music here and there, and you have a movie. At least in the eyes of Paul W.S. Anderson.

Every actor in the ensemble inhabits a paper-thin role, allowing for the film’s violence to take precedence over the characters. Fishburne’s deep, commanding voice makes him captain-like, whereas Neill’s presence alone adds a sinister edge to his obsessed scientist. Other cast members include Joely Richardson, Kathleen Quinlan, Jason Isaacs, Jack Noseworthy, Richard T. Jones, and Sean Pertwee. They’re all anonymous human fodder turned into playthings for Anderson’s nightmare hellscape in space, whose gore should’ve received top billing. Pertwee is blown to smithereens. Isaacs is disemboweled and then strung up by wires and meat hooks. Noseworthy’s character goes into space without the required spacesuit, and the result isn’t pretty.

So why is Event Horizon regarded with such high esteem by cultists? How is this film any different than Anderson’s own Alien vs. Predator or Death Race? What do its followers see that critics are missing? Whereas the cult classic status of something like The Mist or Zombieland comes vindicated by a stylish-if-non-mainstream product, here’s a small phenomenon that’s altogether baffling, the result of impressive home video sales and frequent airings on late-night cable television. Horror fans have elevated the film to ridiculous degrees, which can only be attributed to its wowing capacity for brutal descriptions of incomprehensible violence, challenging even Hellraiser in its disturbing yuck factor.

Production designer Joseph Bennett may be the film’s sole redeemer. In conceiving the picture’s admittedly striking look, he brings to life green glowing corridors and the chilling Gravity Drive—the latter being an actual setpiece and not some computer-animated effect. His designs might not be as practical as some other science-fiction spacecraft, with its pointless ornamentation and bizarro shape, but he does what he does with style. The film might suffer from mid-1990s brand CGI, complete with floating zero-gravity debris that looks conspicuously like Flubber, but Bennett’s sets never fail to give Event Horizon’s audience the willies. His work is good enough to surpass Anderson’s substandard direction, demand that viewers overlook the plot, and watch simply for the visual artistry at work.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review