Reader's Choice

Even Dwarfs Started Small

By Brian Eggert |

Even Dwarfs Started Small is a confounding and vivid picture, even by Werner Herzog’s standards. The Bavarian-born director often traffics in sublime assessments of Nature, complex portraits of humanity’s obsessiveness, and ponderings about everything from the death penalty to the internet. In his 1970 picture, his second full-length feature, Herzog explores an isolated asylum on Lanzarote, a volcanic island in the Canary Islands, that houses dwarfs. The institution’s faculty and even passers-by consist of dwarfs as well. Most of the film’s runtime depicts the inmates revolting, chaotically tearing the place down, setting fire to plants, fighting amongst themselves, and harming nearby animals. Is this Herzog’s anthropological study of a marginalized group of people? Is it a metaphor, and if so, for what? Herzog never comes out and explains what it all means; there’s never a character who articulates the lesson the film hopes to impart, and there are no visual clues to its deeper meaning. In the end, the viewer is left to negotiate what the filmmaker intended by this meandering display of bedlam and the persistent considerations about how Herzog captured this footage and how he views dwarfism.

In his memoir, Every Man for Himself and God Against All, Herzog called the film “probably my most radical work,” and he often ranks it among his own favorites. It may also be his most surreal—and that’s saying something about the director of My Son, My Son, What Have Ye Done (2009). Structurally, the film defies a conventional narrative. Once it begins, it’s 96 minutes of pandemonium, with only hints of significant dialogue to interrupt the procession of destruction and maniacal laughter the director conjures in his actors. In this critic’s interpretation, it’s less about the rebellion of the film’s story than a treatise on how humanity is ever-so-close to descending into lizard-brained mayhem. Herzog often explores the blurry line at which humanity and Nature intersect, and here, he turns this idea into a singular experience. Coupled with Herzog’s reticence to explain the meaning of his films, the anarchic scenario supplies such a thin layer of drama that the film lends itself to interpretation.

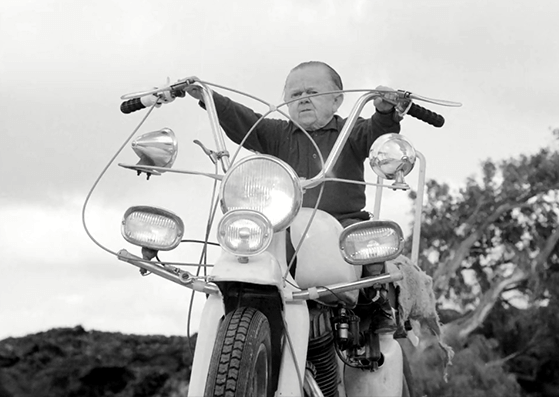

In the first few minutes of screentime, Herzog and his longtime collaborator, cinematographer Thomas Mauch—shooting in crisp black-and-white photography squared by the Academy aspect ratio—calmly examine the institution’s grounds, observing with almost documentary distance the layout and buildings. It’s the calm before the storm; these spaces will soon become the grounds of a frenzied uprising. Early on, the man in charge of the institution, known as The President (Pepi Hermine), ties one of the inmates, Pepe (Gerd Gickel), to a chair. The precise circumstances that led to such dire action remain unclarified. Pepe refuses to speak but, restrained, his maniacal cackling is nonstop. Outside the locked office where The President keeps Pepe, a gaggle of inmates decry their treatment, which is lousy regardless of good or bad behavior. They tear down phone lines and set palm trees ablaze. But their uprising is unfocused, descending into the group forcing a bogus marriage between two inmates or mocking two of their blind compatriots.

Herzog’s treatment of his characters doesn’t encourage much sympathy for their cause. It’s more like witnessing a car accent in slow motion. They start a truck and ride in circles, pulling each other on a rope for fun or playing matador with the vehicle. While filming this scene, one of the actors was run over by the truck but immediately popped up afterward, apparently not seriously harmed. Another actor caught on fire during the scenes where they burned up flowers. The performers were getting so swept up in the action that they were becoming reckless, or maybe it was Herzog who was reckless. The question of whether or not Herzog brings these extraordinary disasters upon himself seems to be ever-present in his films. In any case, Herzog made a promise to his actors: If they remained safe for the rest of the shoot, he would throw himself into a cactus. They did, and so the director put on goggles and leaped into a cactus, requiring a painful process of freeing himself and extracting the long needles.

Herzog’s treatment of his characters doesn’t encourage much sympathy for their cause. It’s more like witnessing a car accent in slow motion. They start a truck and ride in circles, pulling each other on a rope for fun or playing matador with the vehicle. While filming this scene, one of the actors was run over by the truck but immediately popped up afterward, apparently not seriously harmed. Another actor caught on fire during the scenes where they burned up flowers. The performers were getting so swept up in the action that they were becoming reckless, or maybe it was Herzog who was reckless. The question of whether or not Herzog brings these extraordinary disasters upon himself seems to be ever-present in his films. In any case, Herzog made a promise to his actors: If they remained safe for the rest of the shoot, he would throw himself into a cactus. They did, and so the director put on goggles and leaped into a cactus, requiring a painful process of freeing himself and extracting the long needles.

Herzog started making Even Dwarfs Started Small right after completing work on his documentary feature in Africa, Fata Morgana (1971), and as usual, he completed the script in “maybe four or five days,” he told interviewer Paul Cronin. The shoot lasted about five weeks, and Herzog’s experience making the documentary had been so protracted and difficult that he lashed out at the world with this film. “If Goya and Hieronymus Bosch had the guts to do their gloomiest stuff,” he remarked, “why shouldn’t I?” Herzog holds his camera on disturbing scenes where the inmates poke at a dead sow and her orphaned piglets or simply laugh endlessly. On the prominently featured characters, Hombré (Helmut Döring), chuckles to himself about “Mother Nature” and “the cops” in unconnected thoughts. Later, they tie down a monkey for a mock crucifixion—a scene that managed to upset both the Catholic Church and animal rights activists. But for all of their efforts, their rebellion is a failure.

Most troubling is how Herzog and editor Beate Mainka-Jellinghaus juxtapose the dwarfs’ rampage with the rogue chickens around the institution. Besides the dwarfs arranging a cockfight, the chickens have their own side story. Several of them fight over a dead mouse, taunt a fellow chicken with a missing leg, or peck at a dead chicken. These segments are intercut throughout the film, often set to African tribal music—captured near the Ivory Coast while Herzog was shooting his documentary short The Flying Doctors of East Africa (1969). The association between the dwarfs’ actions and the chickens makes them both, in Herzog’s rendering, part of distinct tribes. But the link between the two becomes disturbing given the director’s later remarks about his view of chickens. Herzog once told an interviewer, “Look into the eyes of a chicken, and you will see real stupidity. It is a kind of bottomless stupidity, a fiendish stupidity. They are the most horrifying, cannibalistic, and nightmarish creatures in the world.” Given the onscreen association in this film, it’s difficult to ignore this quote and not consider whether Herzog feels the same way about his characters or dwarfism. Has he made a kind of then-modern freak show of sub-humanity?

Interpretations of Even Dwarfs Started Small range from politically confronting to bewilderment to adulation. After screening the film at the New York Film Festival, Vincent Canby assessed its “essential meaninglessness” and called it “indistinguishable from its Germanic, side-show spectacle, as if it were a movie that had been conceived by the same kind of perverse, uninvolved intelligence that had created the world of the film.” After the film’s release, various groups saw the film as a condemnation of their ideas. Made not long after the student riots in Paris and similar revolts the world over, groups felt the film derided their attempts to create change through rebellion. “Actually, that is probably the one thing they might have been right about,” Herzog told Cronin. He admits that he was “ridiculing the world revolution […] rather than reclaiming it.” Elsewhere, members of a German white supremacist group contacted Herzog after the film’s release and told the director he was high on their kill list, having apparently felt the dwarfs were symbols for them.

Interpretations of Even Dwarfs Started Small range from politically confronting to bewilderment to adulation. After screening the film at the New York Film Festival, Vincent Canby assessed its “essential meaninglessness” and called it “indistinguishable from its Germanic, side-show spectacle, as if it were a movie that had been conceived by the same kind of perverse, uninvolved intelligence that had created the world of the film.” After the film’s release, various groups saw the film as a condemnation of their ideas. Made not long after the student riots in Paris and similar revolts the world over, groups felt the film derided their attempts to create change through rebellion. “Actually, that is probably the one thing they might have been right about,” Herzog told Cronin. He admits that he was “ridiculing the world revolution […] rather than reclaiming it.” Elsewhere, members of a German white supremacist group contacted Herzog after the film’s release and told the director he was high on their kill list, having apparently felt the dwarfs were symbols for them.

Such reactions reveal a couple of things about the film: First, it clearly struck a chord with some groups, inciting them to feel affronted by the association. Second, it reveals that the film, whether intentional or not, presents the dwarfs as horrific and pathetic. Their treatment stings with a pang of Otherness that, similar to Tod Browning’s Freaks (1932), is ultimately exploitative; although, Browning’s film offered more by way of human dignity in his film. Herzog maintains that the failed revolt isn’t a defeat because “for them it is a really good, memorable day; you can see the joy in their faces.” He also claims that he did not intend the dwarfs to be monstrous: “It is us and the society we have created for ourselves.” His rationale and defense are poorly thought out, however, claiming that “We all have a dwarf inside us,” which turns his actors’ very real identities into the personification of a fear of powerlessness. He adds, “It is a very real nightmare for some people who wake up at night and know that basically, deep down, they are just a midget.” Herzog even remarks that while filming Even Dwarfs Started Small, he would wake up terrified that he had transformed into a dwarf overnight, an admission that reveals how he sees his actors’ place in the world.

Throughout his career, Herzog has explored what he calls “ecstatic truth,” which he defines as constants about life that can only be uncovered through poetic or artistic expression. Whether he achieves this by heading into the Peruvian jungle in Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972) or again in Fitzcarraldo (1982), or by subjecting several film crews to the volatility of Klaus Kinski, Herzog often resorts to extremes. Even while being aware of this, Even Dwarfs Started Small forces questions about his attitude toward his actors and their marginalized role in the world; rather than treating them with dignity, he uses them as part of his poetic expression. While those ideas leave the viewer with a bad taste, the worldview he espouses through them is bleak and, pointedly, Herzogian in its assessment of humanity as feeble, disorganized, base, and far from its civilized ambitions. What’s undeniable about the film is that there’s never been anything quite like it before or since, and whatever the ethics involved in the filmmaker’s view of dwarfism, it must be seen and discussed as compelling, undeniably evocative art.

(Note: This review was originally posted to Patreon on December 1, 2023. Many thanks to Steve for requesting this review and for your Patronage!)

Bibliography:

Cronin, Paul. Herzog on Herzog. London: Faber and Faber, 2002.

—. Werner Herzog: A Guide for the Perplexed. Faber & Faber, 2020.

Herzog, Werner. Every Man for Himself and God Against All: A Memoir. Penguin Press, 2023.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review