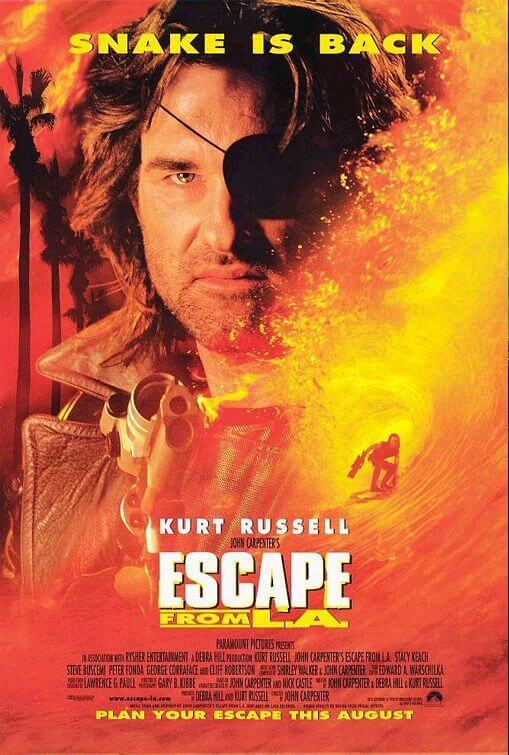

Escape from L.A.

By Brian Eggert |

After years of commercial failures and lost creative battles against various studios, John Carpenter delivered his most acerbic blow against Hollywood with Escape from L.A., his pseudo-sequel to 1981’s cult classic Escape from New York. More a vague remake than a true sequel, the 1996 release represents the famously cynical director’s most contemptuous film, where he lashes out against everyone from studio execs to Disneyland, from the American President to the plastic surgery-addicted culture of Los Angeles. Unfortunately, the film forgoes any grand attempts at narrative originality or technical precision in favor of its message, which is delivered in a number of harsh episodes and encounters involving legendary eye-patched anti-hero Snake Plissken, played to badass perfection by Kurt Russell. Escape from L.A. marks an angry, campy, and over-ambitious project, reminiscent, at least in its intent, of so much cult fare from yesteryear where a social commentary is trapped inside a B-movie presentation (think The Stuff). Even on those terms, Escape from L.A. remains troublesome because of its unclear relationship with its predecessor, if not an admirable effort for its fleeting entertainment value and palpable anger. The key to enjoying the film is setting aside the presentation and dwelling on what Carpenter hoped to say about Hollywood.

More significantly in the realm of Carpenter’s career, Escape from L.A. marks the first major sign the director was burning out, that the studio struggles and underwhelming reception of his then-recent films had incited him to consider an unofficial retirement. Carpenter had made 17 features for either theatrical or television release in the previous twenty years; by comparison, he made only three features in the twenty years following Escape from L.A. All signs pointed to a director growing tired of his craft—that playing the Hollywood game and fighting for artistic integrity when it was rarely delivered had worn him down. His (justifiably) self-proclaimed masterpiece The Thing had bombed, he sacrificed creative control on larger budgeted films, and he collided with studios on titles like Memoirs of an Invisible Man (1993) and Village of the Damned (1995). And after Escape from L.A., he released three failures: the lackluster Vampires (1998), the enjoyable flop Ghosts of Mars (2001), and as of this assessment, Carpenter hasn’t made another film since his ill-received indie The Ward (2010). Indeed, Escape from L.A. seems to signify a paradigm shift in Carpenter’s career, not only as an important change in his perspective and attitude as a director, but also his ensuing technical laziness as a filmmaker, resulting in the poor reception of his works both critically and commercially.

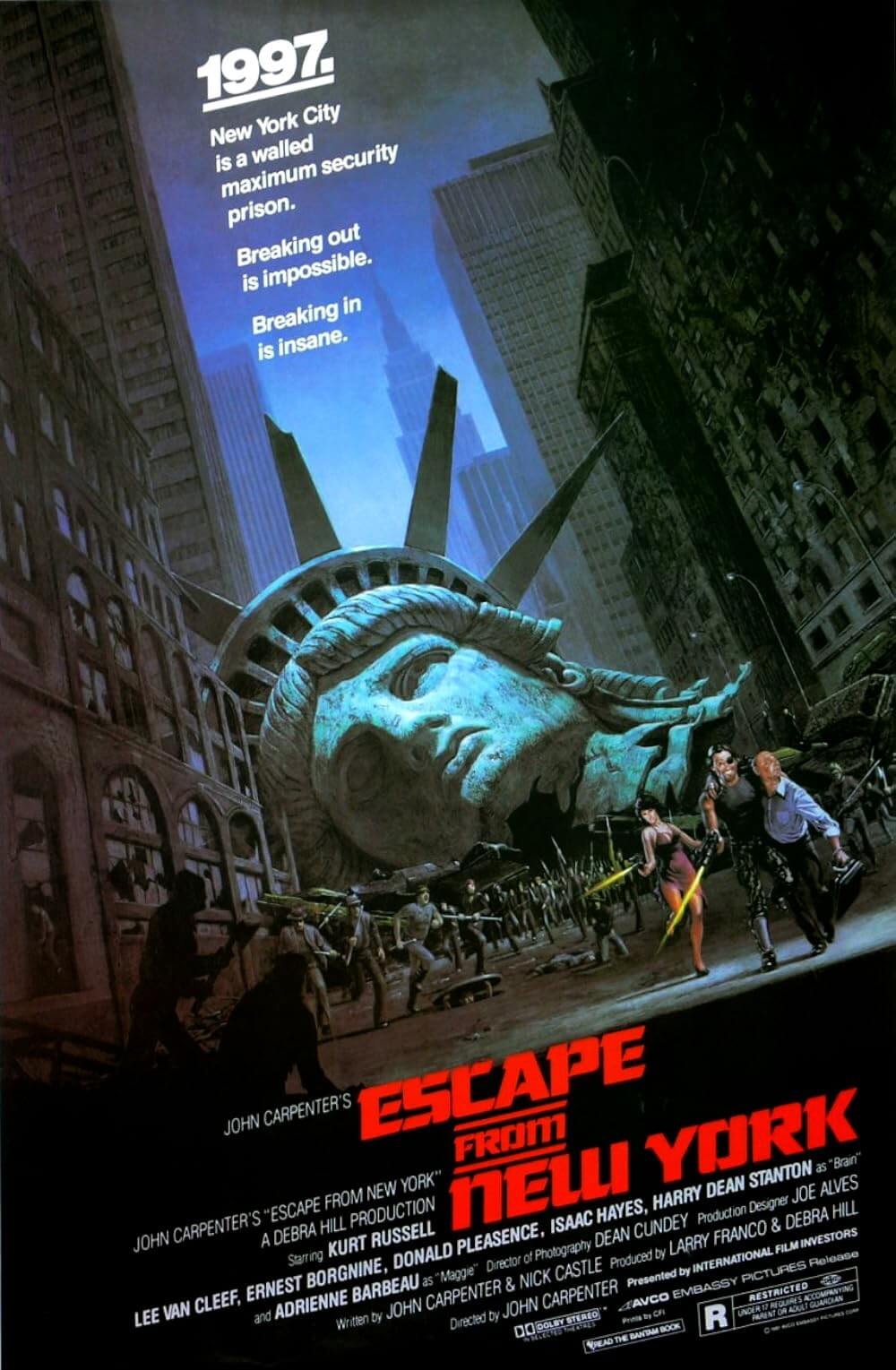

Since Escape from New York earned a respectable profit at the box-office, talk of a sequel began shortly after its debut. Already in the business of sequels after his breakthrough Halloween (1978) and its follow-up Halloween II (1981, written by Carpenter and producer Debra Hill, direction credited to Rick Rosenthal), Carpenter hired television writer Coleman Luck to write a sequel to Escape from New York in 1985, but the draft he delivered was unsatisfactory. The notion of a sequel remained on the backburner until the mid-1990s, when both Carpenter and Russell expressed interest in revisiting the material and character. Along with his longtime producer Debra Hill, Carpenter began writing the script with contributions from Russell, and before long the nostalgia of this group working together again resulted in, what started as, homages to the original, eventually evolving into a veritable remake. Indeed, the film’s structure and plot closely adhere to those of the original, the film opening with a narrated introduction: In the year 2000, an earthquake predicted by the ultra-right-wing President (Cliff Robertson) strikes California, the Pacific Ocean floods the San Fernando Valley, and the remaining island of Los Angeles becomes a prison where the new “Moral America” dumps its rejects.

Since Escape from New York earned a respectable profit at the box-office, talk of a sequel began shortly after its debut. Already in the business of sequels after his breakthrough Halloween (1978) and its follow-up Halloween II (1981, written by Carpenter and producer Debra Hill, direction credited to Rick Rosenthal), Carpenter hired television writer Coleman Luck to write a sequel to Escape from New York in 1985, but the draft he delivered was unsatisfactory. The notion of a sequel remained on the backburner until the mid-1990s, when both Carpenter and Russell expressed interest in revisiting the material and character. Along with his longtime producer Debra Hill, Carpenter began writing the script with contributions from Russell, and before long the nostalgia of this group working together again resulted in, what started as, homages to the original, eventually evolving into a veritable remake. Indeed, the film’s structure and plot closely adhere to those of the original, the film opening with a narrated introduction: In the year 2000, an earthquake predicted by the ultra-right-wing President (Cliff Robertson) strikes California, the Pacific Ocean floods the San Fernando Valley, and the remaining island of Los Angeles becomes a prison where the new “Moral America” dumps its rejects.

Enter Snake Plissken, the former military hero turned criminal anti-hero, caught once again by his government and doomed to Los Angeles Prison. Fortunately, the President’s rebellious daughter Utopia (A.J. Langer) has sided with the Shining Path Peruvian Revolutionary’s leader, Cuervo Jones (Georges Corraface), stealing the U.S. government’s ultimate weapon, the “Sword of Damocles”, which uses satellites to shut down any source of electricity within a targeted area. With it, Cuervo could shut down all power in America. This is fortunate for Snake because the President needs him to recover the weapon from Utopia and Cuervo, both inside L.A. Prison. Within the first moments, the audience recognizes the similarities between this setup and Escape from New York‘s. The stakes are all-encompassing, the exposition heavy. Stacy Keach plays Malloy, a tough military advisor to the President, not unlike Lee Van Cleef’s Hauk from the original. Malloy walks Snake down a long corridor where he has the option to self-terminate before heading to L.A. Once Snake arrives inside, Steve Buscemi’s well-informed Maps to the Stars Eddie stands in for Cabbie (Ernest Borgnine). The transvestite Hershey (Pam Grier) is analogous to Harry Dean Stanton’s Brain. And Cuervo Jones is clearly a counterpart for Isaac Hayes’ The Duke.

The entire plot structure follows Escape from New York closely, where Snake, on a deadline after being poisoned by his government, enters the island prison, uses friends inside to launch a rescue, and then escapes, only to double-cross the U.S. government. But the world Carpenter establishes contains far more detail and proves much bleaker. Snake himself seems defeated, more cynical than he was in the preceding film. As he makes his way through Los Angeles Prison, Snake is stopped and asked, “So they got to you too?” Snake replies, “Sooner or later, they get everybody.” Another inmate asks, “What are you doing in L.A.?” He growls, “Dyin’.” Yet another inmate questions, “You’re Snake Plissken, aren’t you?” Snake replies, “Used to be.” Whereas the name “Snake” was once the character’s own moniker, adopted in rejection of his name otherwise associated with the U.S. military, he’s now so commonly known as Snake that he no longer wants the name. There is no identity for Snake that remains his own, because the world he inhabits is not of his own making.

The entire plot structure follows Escape from New York closely, where Snake, on a deadline after being poisoned by his government, enters the island prison, uses friends inside to launch a rescue, and then escapes, only to double-cross the U.S. government. But the world Carpenter establishes contains far more detail and proves much bleaker. Snake himself seems defeated, more cynical than he was in the preceding film. As he makes his way through Los Angeles Prison, Snake is stopped and asked, “So they got to you too?” Snake replies, “Sooner or later, they get everybody.” Another inmate asks, “What are you doing in L.A.?” He growls, “Dyin’.” Yet another inmate questions, “You’re Snake Plissken, aren’t you?” Snake replies, “Used to be.” Whereas the name “Snake” was once the character’s own moniker, adopted in rejection of his name otherwise associated with the U.S. military, he’s now so commonly known as Snake that he no longer wants the name. There is no identity for Snake that remains his own, because the world he inhabits is not of his own making.

Singularity is an important idea for Snake Plissken in both films. But the depiction of Snake’s particularly grim worldview in Escape from L.A. forces one to ponder why the character keeps going. All throughout Escape from L.A., Carpenter embraces Snake’s individualistic code, representing the character like a lone samurai or gunslinger, specifically of origin in the Western genre. At one point in the film, four men corner Snake. As he suggests a “Bangkok Rules” standoff, and a harmonica score reminiscent of Ennio Morricone’s music echoes under the scene. Snake tosses a can in the air, and when it hits the ground, the men are supposed to draw. But when he sends the can up and their eyes follow it, Snake fires two shots from each of his guns, dropping all four men. “Draw,” he says, recalling characters from Sergio Leone Westerns: Charles Bronson’s unnamed character Harmonica from Once Upon a Time in the West or Clint Eastwood’s Man with No Name. That both Leone characters are nameless helps shape Snake’s identity in the film. Staying “off the grid” and making his own world—a world of crime—allows Snake his only freedom, which of course lands him in jail. With his freedom gone, so is Snake’s identity. The hope of maintaining an identity when the world around you is far removed from anything you would choose tells us much about Snake Plissken, but also Carpenter.

According to author Robert C. Chumbow in his book Order in the Universe: The Films of John Carpenter, Escape from L.A. was designed to be “Carpenter’s hate letter to the industry and the whole Southern California lifestyle.” A sequence where underground freaks capture Snake and his short-lived female cohort Taslima (Valeria Golino, playing the equivalent of Season Hubley’s role from the original) and deliver them to the Surgeon General of Beverly Hills (Bruce Campbell), shows us that plastic surgery addicts now capture norms to maintain their own drooping, artificial faces. Maps to the Stars Eddie remarks “The town loves a winner,” after a crowd turns on Cuervo following Snake’s survival of a basketball “shot clock” challenge, the entire sequence a winking metaphor for how celebrity becomes worshiped by Hollywood. Carpenter’s President is a sly, if none-too-subtle parody of Pat Robertson—who deemed L.A. responsible for the insurgence of ultra-violent cinema in the 1990s (Wild at Heart, Natural Born Killers)—serving as the racist, homophobic high chieftain of the “Moral Right” who damns the violent Los Angeles. Through Carpenter’s worldview, not even Cuervo Jones is authentic; in fact, he’s nothing more than an ersatz Che Guevara wannabe bent on power.

According to author Robert C. Chumbow in his book Order in the Universe: The Films of John Carpenter, Escape from L.A. was designed to be “Carpenter’s hate letter to the industry and the whole Southern California lifestyle.” A sequence where underground freaks capture Snake and his short-lived female cohort Taslima (Valeria Golino, playing the equivalent of Season Hubley’s role from the original) and deliver them to the Surgeon General of Beverly Hills (Bruce Campbell), shows us that plastic surgery addicts now capture norms to maintain their own drooping, artificial faces. Maps to the Stars Eddie remarks “The town loves a winner,” after a crowd turns on Cuervo following Snake’s survival of a basketball “shot clock” challenge, the entire sequence a winking metaphor for how celebrity becomes worshiped by Hollywood. Carpenter’s President is a sly, if none-too-subtle parody of Pat Robertson—who deemed L.A. responsible for the insurgence of ultra-violent cinema in the 1990s (Wild at Heart, Natural Born Killers)—serving as the racist, homophobic high chieftain of the “Moral Right” who damns the violent Los Angeles. Through Carpenter’s worldview, not even Cuervo Jones is authentic; in fact, he’s nothing more than an ersatz Che Guevara wannabe bent on power.

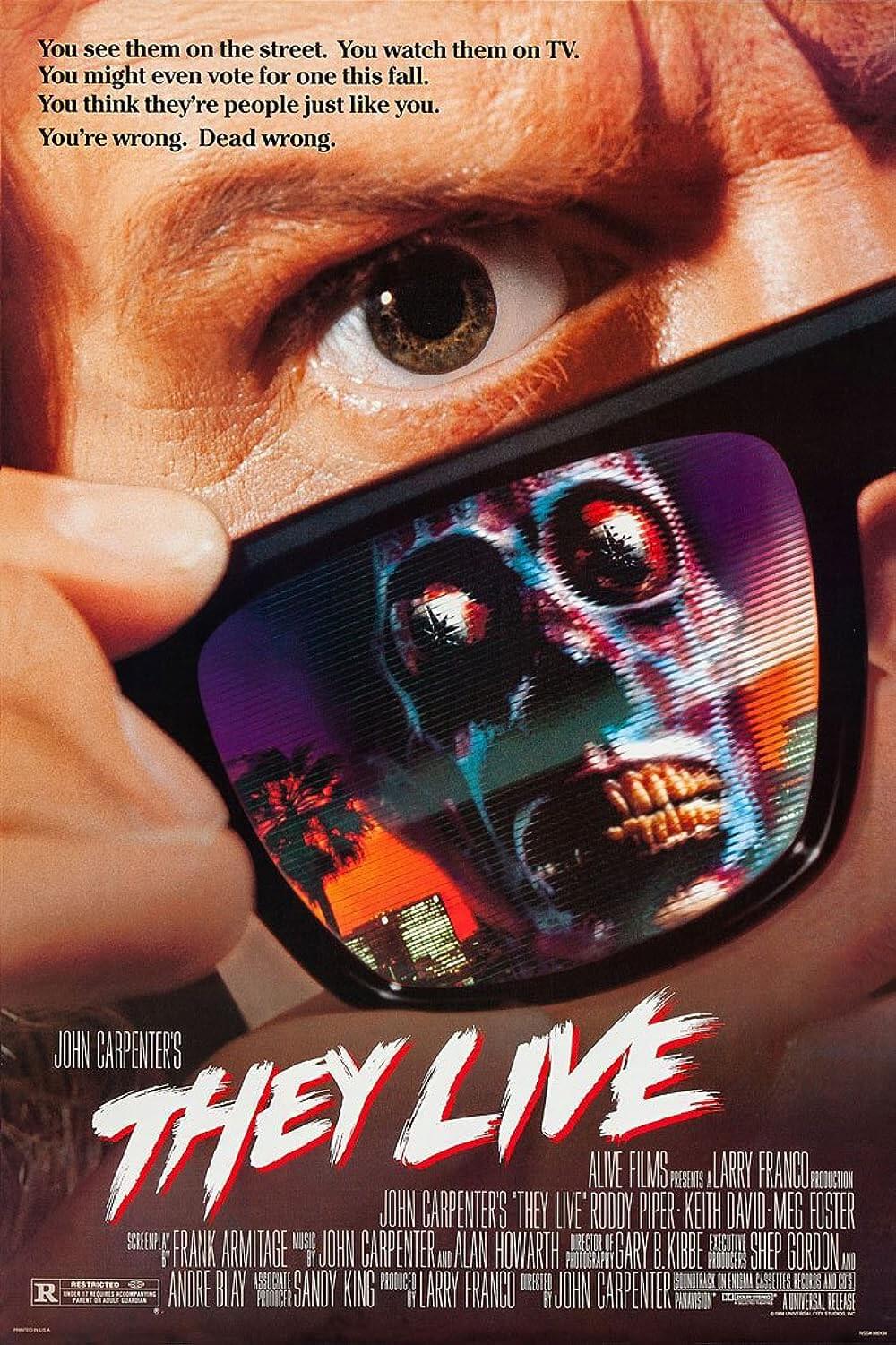

Earlier, Cuervo proclaims, “This fucking city can kill anybody,” and it becomes impossible not to see Carpenter’s disdain for how Hollywood chews up filmmakers and spits them out. But like a true B-movie, in the end, Snake bests both sides of the opposition, not unlike the final moments of Escape from New York. The President wants the “Sword of Damocles” to bring moral order to America; Cuervo wants it to enforce his new chaotic authority. Snake has no tolerance for authority in any form. He sees through authority and despises it. When he returns to U.S. soil with Utopia saved and the “Sword of Damocles” in hand, he uses a switcheroo to carry out Cuervo’s threat, which was ultimately a bluff, that he would render the world powerless. After all, Cuervo hungered too much for power to actually go through with his plan. The final scene shows Snake doing the same thing Cuervo threatened to, returning the world “to the Stone Age” by zapping out all electronics. Except, Cuervo’s plan was murderous and power-hungry, whereas Snake’s execution is a mercy killing on a dead world. After pressing the button, Snake lights a match, ponders it, then looks at the audience, breaking the fourth wall, and blows it out. “Welcome to the human race,” he says. This level of cynicism from Carpenter has only been matched by They Live, the director’s 1988 feature about The Powers That Be secretly being aliens in disguise.

Never quite reconciling whether it’s a Hollywood satire or diverting action yarn, or both, Escape from L.A. remains an enjoyable mess, a flop that earned back just over half of its $50 million budget and received primarily negative reviews. In 1996, $50 million should have provided Carpenter with A-list special FX and visual wonders. But the film contains curiously bad computer-generated images, beginning with shoddy animations of Los Angeles tumbling into the ocean. While Snake drives his cartoonish submarine to the island prison, he passes by Universal Studios and narrowly escapes a laughably rendered shark (viewers couldn’t be blamed for thinking the shark is actually the “Bruce” puppet from Jaws floating in Universal, but in fact Carpenter meant the animated creature to be real). Elsewhere, Snake surfs alongside Peter Fonda in an oddball sequence; accomplishes a 50-yard motorcycle jump onto the back of a pickup; hang-glides down on Cuervo’s party; and narrowly evades a missile in a videogame helicopter, next to Disneyland’s Matterhorn Bobsleds mountain. Rather than spend his large budget and make a few scenes look spectacular, Carpenter makes the unfortunate choice to spread his budget thin, resulting in a visual letdown.

Never quite reconciling whether it’s a Hollywood satire or diverting action yarn, or both, Escape from L.A. remains an enjoyable mess, a flop that earned back just over half of its $50 million budget and received primarily negative reviews. In 1996, $50 million should have provided Carpenter with A-list special FX and visual wonders. But the film contains curiously bad computer-generated images, beginning with shoddy animations of Los Angeles tumbling into the ocean. While Snake drives his cartoonish submarine to the island prison, he passes by Universal Studios and narrowly escapes a laughably rendered shark (viewers couldn’t be blamed for thinking the shark is actually the “Bruce” puppet from Jaws floating in Universal, but in fact Carpenter meant the animated creature to be real). Elsewhere, Snake surfs alongside Peter Fonda in an oddball sequence; accomplishes a 50-yard motorcycle jump onto the back of a pickup; hang-glides down on Cuervo’s party; and narrowly evades a missile in a videogame helicopter, next to Disneyland’s Matterhorn Bobsleds mountain. Rather than spend his large budget and make a few scenes look spectacular, Carpenter makes the unfortunate choice to spread his budget thin, resulting in a visual letdown.

With every screening, there are elements to savor and others to revile about Escape from L.A. The laughably cheap CGI and blatant similarities to Escape from New York are incredibly distracting. Instead, if viewers focus on what Carpenter is trying to say, as opposed to the half-hearted method in which he tries to say it, Escape from L.A. becomes a guilty pleasure and thought-provoking look at Carpenter’s worldview. Moreover, in a touch of historic irony, audiences have learned nothing from the cautionary tales present in either of Carpenter’s films about Snake Plissken; and if released today, it might even be condemned as overly anti-American, with Carpenter left to be branded a cinematic terrorist. But the film is also a bastion of free speech (which seems even more regulated and condemned today than in 1996). In a telling early scene where Malloy tries to convince Snake to take the mission, he warns, “This is your last chance, hotshot.” Snake grumbles, “For what?” Malloy boasts, “Freedom.” Snake can only reply, “In America? That died a long time ago.”

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

As the season turns toward gratitude, I’m reminded how fortunate I am to have readers who return week after week to engage with Deep Focus Review’s independent film criticism. When in-depth writing about cinema grows rarer each year, your time and attention mean more than ever.

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your moviegoing—whether it’s context, insight, or simply a deeper appreciation of the art form—I invite you to consider supporting it. Your contributions help sustain the reviews and essays you read here, and they keep this space independent.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review