EO

By Brian Eggert |

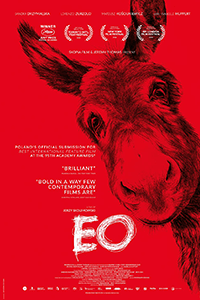

Jerzy Skolimowski’s EO, about a donkey bearing silent witness to a range of human behavior, much of it awful, belongs to a rare breed of films about animals. It’s not a talking animal adventure in the tradition of live-action Disney movies such as Homeward Bound: The Incredible Journey (1993), nor a Marley & Me (2008) tearjerker where human characters feel big emotions because of the resident dog. Instead, the Polish filmmaker draws from Robert Bresson’s 1966 drama Au hasard Balthazar, an intellectual parable where the donkey might stand for a beleaguered Christ, passively suffering for all humankind. But Skolimowski doesn’t have anything so theological or stylistically austere in mind. Regardless of the DNA his film shares with Besson’s masterpiece, Skolimowski creates a dynamic, energized, red-strobed piece of filmmaking that never feels like the work of an 84-year-old directing veteran who got his start during the Polish New Wave. Immersing itself in animal subjectivity, EO is an empathetic yet ultimately unflinching look at humanity’s indifference to the intelligence and emotions of our fellow beasts.

EO marks another recent film that immerses the viewer in animal experiences. On the 2021 festival circuit, Andrea Arnold’s almost wordless cinéma vérité documentary charted the deeply depressing life of a dairy cow, offering occasional beauty amid the wide-angled misery and delivering perhaps the best (albeit deeply unpleasant) argument for veganism ever filmed. Skolimowski’s approach has several similarities, from his use of the boxy Academy aspect ratio to his frequent off-kilter angles that suggest the animal’s distinct view of the world. Like Arnold’s film, it’s also the work of a director who loves animals and wants the viewer to identify with them as creatures capable of emotion, prompting us to leave the theater and yearn to protect them from harm in any number of vile industries. Admittedly, I prefer my cinematic animal rights activism in the form of artificial animals, such as the CGI superpig from Bong Joon-ho’s Okja (2015), where there’s no reason to doubt the American Humane disclaimer that “no animals were harmed” because no real animals appeared in the film.

In a picaresque structure, EO, a circus donkey in Poland, passes from one owner to another, sometimes through official channels, and others by wandering into someone’s company. The film rolls effortlessly among these episodes, lending few dimensions to EO’s human counterparts. Meanwhile, EO seems at odds with the world—either exploited or part of an unnatural environment. The donkey begins in the loving care of a circus performer, Kasandra (Sandra Drzymalska). But the circus illegally uses animals, so officials tear our protagonist from Kasandra and place him into a stable amid horses who receive baths and luxuries while EO receives hard labor. Later sold to rural farmers who use donkeys for gentle interactions with special needs children, EO sees flashes of Kasandra in his mind until, finally, she visits him. And after she leaves due to a spat with her boyfriend, EO escapes the farm to find her and wanders through a fairy-tale wilderness filled with an owl, a fox, and wolves—an otherwise serene moment interrupted by hunters with laser-guided rifles. His encounters with footballers, a trucker with an affinity for heavy metal, and a drifter (Mateusz Kościukiewicz) who returns home to a loaded relationship with his countess mother (Isabelle Huppert), feel almost improvised, ultimately leading EO to a grim fate.

Written along with Skolimowski’s wife and co-producer, Ewa Piaskowska, EO creates a bond with the rather adorable donkey through close proximity. Visually, the film adopts a similar technique as Arnold’s Cow to capture the donkey’s subjectivity—Skolimowski and cinematographer Michał Dymek place the camera near the animal’s face, allowing a wide-angle lens to enlarge EO’s massive, expressive eyes. Through them, we see glimpses of what EO yearns for—Kassandra, carrots, and freedom to explore. The film carries its technique throughout, giving viewers a donkey-eyed worldview. Skolimowski also deploys boldly stylized, red-hued scenes of trauma; searching drone shots that hover over the Polish landscape; and more objective, observational shots that establish the setting. The energized filmmaking, not always consistent in a form-follows-function methodology, gives EO the sense that anything can happen. From one episode to the next, Skolimowski delights in keeping the viewer off-balance, and there’s a particular joy in seeing the filmmaker experiment with form.

Written along with Skolimowski’s wife and co-producer, Ewa Piaskowska, EO creates a bond with the rather adorable donkey through close proximity. Visually, the film adopts a similar technique as Arnold’s Cow to capture the donkey’s subjectivity—Skolimowski and cinematographer Michał Dymek place the camera near the animal’s face, allowing a wide-angle lens to enlarge EO’s massive, expressive eyes. Through them, we see glimpses of what EO yearns for—Kassandra, carrots, and freedom to explore. The film carries its technique throughout, giving viewers a donkey-eyed worldview. Skolimowski also deploys boldly stylized, red-hued scenes of trauma; searching drone shots that hover over the Polish landscape; and more objective, observational shots that establish the setting. The energized filmmaking, not always consistent in a form-follows-function methodology, gives EO the sense that anything can happen. From one episode to the next, Skolimowski delights in keeping the viewer off-balance, and there’s a particular joy in seeing the filmmaker experiment with form.

Capped with the familiar “no animals were harmed” disclaimer and a message explaining the film’s animal-friendly intent, EO avoids putting the central donkey (played by six similar-looking Sicilian donkeys) in peril. When a group of angry footballers blames EO for their team losing and resolve to beat him, Skolimowski and editor Agnieszka Glińska use POV shots that never show the donkey harmed onscreen. Whatever its intentions, EO nonetheless raises questions about the ethics of using animals in any film production. Take a scene set amid a row of cages with terrified foxes inside. The camera peers inside, and the foxes look horrified about what comes next. After all, these foxes aren’t actors, so for the purposes of his film, Skolimowski terrified animals who may not have been harmed physically but probably felt great fear and anxiety as a result of the scene. Despite the production’s reassurances, EO will doubtlessly make anyone with an affinity for animals disturbed by what Skolimowski puts on camera, both in terms of what he depicts and what it took to capture the shot—even if carried out with the utmost care.

EO earned a Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Festival and is Poland’s entry for the Best International Feature category at the Oscars. It has been widely praised among European festivals and critics groups domestically and abroad. Still, when EO’s final abrupt shot leads to a disquieting conclusion, I found myself feeling Skolimowski hadn’t convinced me of anything new—I already felt that animals are living creatures with minds and emotions. They’re not humans, of course, but they deserve our respect and consideration, every bit as much as our fellow humans do. Although I agree with Skolimowski’s message and outlook on animals—that they live in a harsh world, and we should do more to improve their lives—the film’s constant tension, both textual and extratextual, left me wondering whether the shattering result was worth putting these beings through the stress of the production. I cannot answer that question. But in the same way that I refuse to read grim emails from the ASPCA but will gladly donate to their cause, Skolimowski has made an unquestionably heartfelt and challenging film that I never want to watch again.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review