End of Watch

By Brian Eggert |

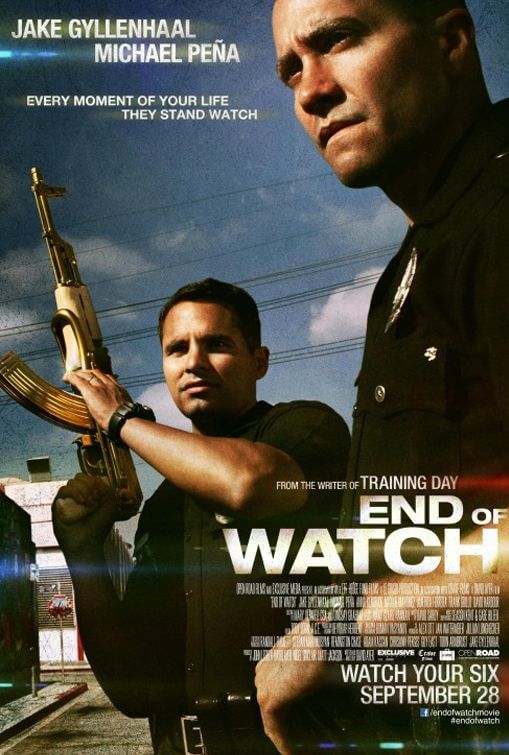

Both as writer and director, David Ayer has made some of the best cop movies in recent years, all of them set in Los Angeles. He wrote Training Day and Dark Blue, made his directing debut with Harsh Times and later helmed Street Kings, and now he’s written and directed End of Watch. This moving and exciting L.A. cop movie is devoid of overused corruption stereotypes and refreshingly infused with the theme of brotherhood between officers. Its two central characters, partners Brian Taylor (Jake Gyllenhaal) and Mike Zavala (Michael Peña), patrol their dangerous South Central beat, an area wrought by gang violence, relying on each other through every criminal encounter. But Ayer resists depicting them as crooked or jaded officers, although his previous work has explored police corruption in sometimes over-the-top ways. Instead, he delivers a buddy cop story in which his characters are hard-working good guys who uphold the law. How novel.

To do this, Ayer takes an almost reality-TV-by-way-of-Cops approach. Taylor, who’s enrolled in a night film course, decides to record their experiences on patrol for a project by carrying a handheld camera. He also fixes small cameras to Zavala and himself during their beat, although his supervisor warns him against it. This pseudo “found footage” setup allows for point-of-view angles and an endless shaky-cam effect courtesy of Roman Vasyanov’s gritty lensing, which brings a high-energy tone to their car chases and shootouts. Moreover, we see shots from the perspective of Hispanic and African American gang cameras, which inevitably cause a blend of cop and gang footage when the two groups converge. Ayer’s visual technique as it relates to its implementation in the story, however, is inconsistent. If we’re to believe all footage onscreen is from a character’s camera, Ayer’s periodic use of aerial shots and establishing shots feel out of place, as do intimate moments where the camera takes an anonymous third-party perspective when the scene hasn’t supplied this third party. More consistent use of his device would have allowed the viewer to fall into the material easier, but at times we ask ourselves, “Who’s filming right now?”

Beyond this, Ayer’s cop movie finds a chummy place amid Taylor and Zavala, two hot shots who have a grand sense of camaraderie between them. After taking down a couple of gangbangers in the movie’s opening shootout, the thrill-seeking partners progress on something of a lucky streak. They rescue children from a fire, stumble on a major drug bust, and find a human trafficking hub. Taylor believes their recent arrests might be connected, and he starts playing detective, though doing so is outside his pay grade. At home, Zavala’s pregnant wife Gabby (Natalie Martinez) has just given birth to their first child, and Taylor has met “the one” in Janet (Anna Kendrick), with whom he considers marrying. Meanwhile, their outwardly unconnected drug busts have gained the attention of the cartels, which are expanding into the area. A ruthless band of thugs is enlisted to take down the two cops, and the final 20 minutes of Ayer’s movie unfold as the gangland hit on the cops plays itself out.

Essential are the talents of Gyllenhaal and Peña, who together logged hundreds of ride-along hours with actual LAPD offers in preparation for their roles. As a result, the rapport between these men is felt in their lighthearted banter and every personal or offhand anecdotes they share during their patrols, while moments of action proceed with kinetic veracity. There’s an excess of bromantics here, but it’s to illustrate the solidarity between officers. They call out “brother” and “partner” to one another during scenes of tension and in their frequent heart-to-hearts, a somewhat corny trait that might seem like marketing for a career in law enforcement, if it didn’t feel so genuinely portrayed. Although scenes with Taylor and Zavala’s families don’t quite congeal with the reality-based setup, they provide emotional backing. Their friendship feels natural and deeper than your average buddy cop movie. And though Ayer’s screenplay resorts to some of the clichés we associate with the genre, the performances are so strong that we hardly care.

End of Watch paints a realistic portrait of LAPD patrol officers, and a positive one at that. When so many cynical films (a good number made by Ayer) have little else except censures to throw at the LAPD, how refreshing it is to see a movie where cops are not represented as shady, murderous, or self-destructive. As for Ayer’s formal presentation, the wobbly hand-held camerawork and irregular use of POV shots make the viewing experience nothing short of distracting. Had Ayer maintained the pretense of this effect or simply forgone explaining its use of shaky-cam altogether, the movie would have been saved from countless holes. Fortunately, Gyllenhaal and Peña have such a successful chemistry with one another that their characters’ relationship draws our attention away from the technical annoyances and focuses it on the movie’s main theme of the bond between officers.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review