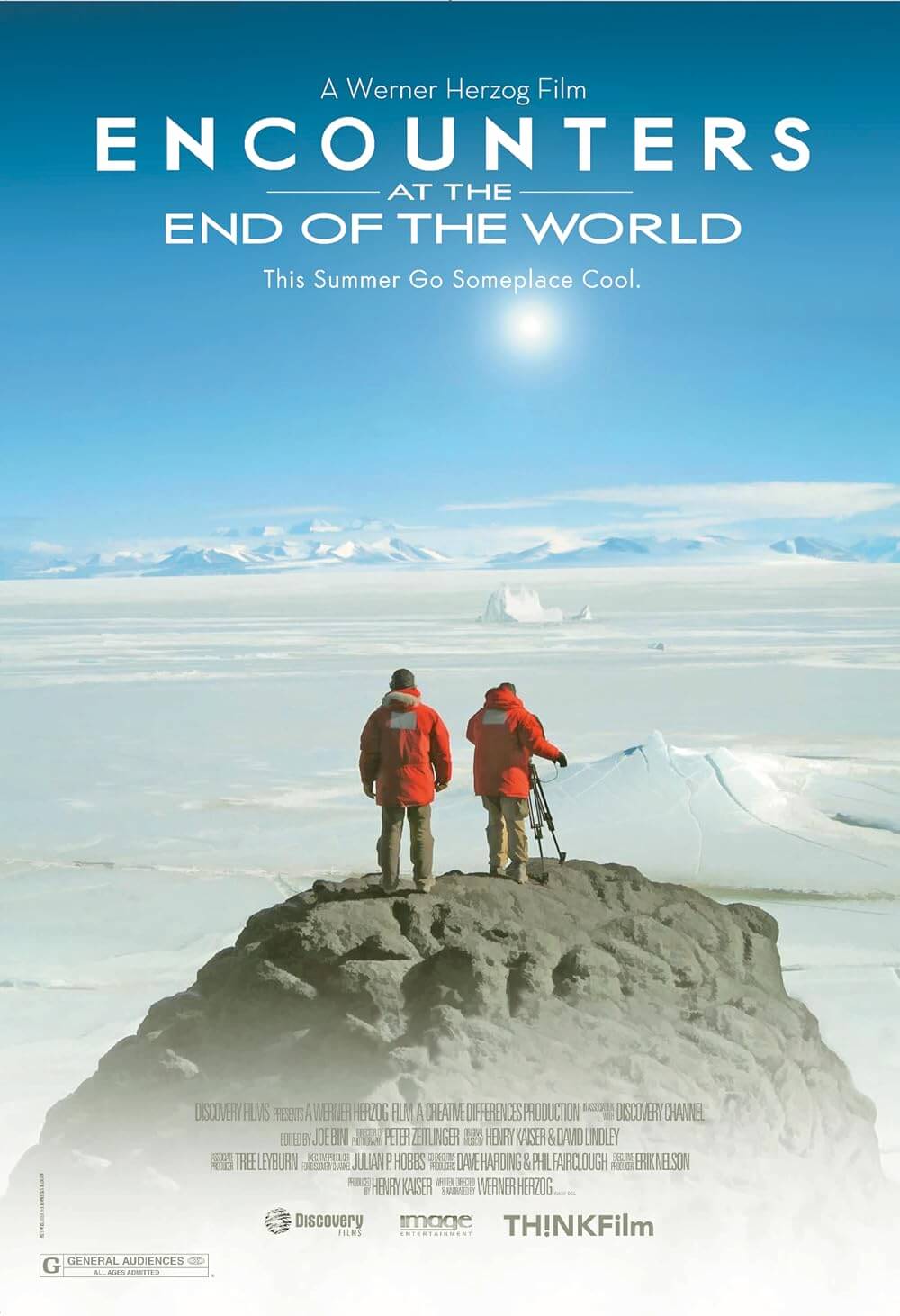

Encounters at the End of the World

By Brian Eggert |

In the opening of Werner Herzog’s Encounters at the End of the World, the director explains that The National Science Foundation provided him with a grant to shoot his documentary after he asked questions about the way humans use Nature: “Why is it that a sophisticated animal like a chimp does not utilize inferior creatures?” Indeed, Herzog sees an imbalance between Nature and humanity, as human beings see themselves outside of Nature and often exploit landscapes or what are perceived to be inferior animals for the benefit of humankind. Rather than relaying endless facts or using animated charts to prove his point, he ventures to Antarctica, where he explores the scientists who live and research there. He shows how humanity’s presence results in a desperate attempt to, in some cases, insert their authority over Nature; in other cases, the scientists there seek to escape humanity. In either case, the harsh and brutal environment reveals the continued disparity between Nature and humankind.

An exceptionally beautiful and thoughtful documentary, Encounters at the End of the World was released in 2007. Herzog became interested in Antarctica during his production of Grizzly Man (2005), whose music producer Henry Kaiser showed the director personal diving footage he took of the Ross Sea at the South Pole. Fascinated by the underwater footage, Herzog applied for and was awarded a grant to shoot a documentary in Antarctica. He had a seven-week window to shoot his film and could make only a single trip, which left no time for location scouting or time to plan interview subjects. Moreover, his team was limited; Herzog and his frequent cinematographer Peter Zeitlinger represented the entire crew. Herzog arrived hoping to find a pure place barely touched by humankind, but what he found at first was that humanity had spoiled Nature. He describes conveniences such as “the ugly mining town” of McMurdo Station and its aerobic studio as “abominations” on the otherwise pure landscape. The viewer can sense his disgust and, before long, he seeks to get away from the somewhat industrialized and tamed center of McMurdo.

Herzog’s interviews consist of scientists who enthusiastically talk about their research projects to the camera; but also laborers, vagabonds, rejects, and escapees of the human world who have found themselves on the edge of the planet. Early on, he talks to caterpillar driver and philosopher Stefan Pashov, a Bulgarian who reflects on how he “fell in love with the world” and adventure after reading The Odyssey. After his remarks, the shot stays there, and Pashov looks both optimistic and sad, thus adding a layer of undefined substance, which Herzog is content not to explore for the mystery it contains about Pashov. The Antarctic scientists and workers place themselves at incredible risk in unrelenting conditions to understand Nature or, in some cases, isolate themselves. Herzog identifies with them through his open subjectivity and search for poetic truth. He seems to find the location and its people inherently dramatic, as the unforgiving yet magnificent landscape requires a certain kind of individual to confront it. Those willing to face such an extreme, sublime form of Nature have an innate quality that Herzog remains fascinated by and curious about. Perhaps it’s because he’s the same way.

Herzog’s interviews consist of scientists who enthusiastically talk about their research projects to the camera; but also laborers, vagabonds, rejects, and escapees of the human world who have found themselves on the edge of the planet. Early on, he talks to caterpillar driver and philosopher Stefan Pashov, a Bulgarian who reflects on how he “fell in love with the world” and adventure after reading The Odyssey. After his remarks, the shot stays there, and Pashov looks both optimistic and sad, thus adding a layer of undefined substance, which Herzog is content not to explore for the mystery it contains about Pashov. The Antarctic scientists and workers place themselves at incredible risk in unrelenting conditions to understand Nature or, in some cases, isolate themselves. Herzog identifies with them through his open subjectivity and search for poetic truth. He seems to find the location and its people inherently dramatic, as the unforgiving yet magnificent landscape requires a certain kind of individual to confront it. Those willing to face such an extreme, sublime form of Nature have an innate quality that Herzog remains fascinated by and curious about. Perhaps it’s because he’s the same way.

Elsewhere, he speaks to mechanic Libor Zicha who escaped the Iron Curtain and remains ready to travel at any moment. Rather than force the man to recount his dramatic escape, Herzog can see the pain on Zicha’s face. In narration, Herzog says, “The tragic events surrounding his escape haunt him to this day.” He tells Zicha, “You do not have to talk about it.” At this moment, the viewer should realize that Herzog isn’t a typical documentarian, obsessed with pushing for facts and details from his interviewees. Herzog searches for poetic truth in what he shoots, whether it be a vast underwater landscape or an emotionally raw character. In his interview with Zicha, the poetry resides not in Herzog’s commentary or how he portrays the scene for his audience—Zicha’s wordless expression is enough. The humanity and truth of Zicha’s readiness, his painful past, and his reason for escaping to Antarctica are all apparent without forcing Zicha’s tale on camera or expanding in any way that might better illuminate unnecessary details.

In other scenes, Herzog stages moments for the truth they provide about the human-Nature dynamic. For example, he arranges a moment where two researchers play electric guitar on top of their bunker to illustrate the solitude of their presence against the white backdrop. An equally staged moment occurs when Herzog shows scientists placing their ears to the ice to listen to hypnotic seal sounds. Beneath the ice, the seals communicate with each other across vast distances, the sounds themselves are reminiscent of science-fiction noises, echoing as if lasers had been shot through space or robots had just learned to communicate in their own language. The scientists have instruments that could listen with more clarity; what is more, they can stand and hear seals without getting down on the ice. But Herzog stages the moment for its truth, how the evocative imagery of listening to ice suggests the sublime world on the other side. Herzog believes that truth can be fabricated through poetic and artistic choices like this one. As long as such creativity results in what Herzog sees as the truth of a scene, the method does not matter, even if his choices bend the documentary’s limits as a subdivision of nonfiction film.

In other scenes, Herzog stages moments for the truth they provide about the human-Nature dynamic. For example, he arranges a moment where two researchers play electric guitar on top of their bunker to illustrate the solitude of their presence against the white backdrop. An equally staged moment occurs when Herzog shows scientists placing their ears to the ice to listen to hypnotic seal sounds. Beneath the ice, the seals communicate with each other across vast distances, the sounds themselves are reminiscent of science-fiction noises, echoing as if lasers had been shot through space or robots had just learned to communicate in their own language. The scientists have instruments that could listen with more clarity; what is more, they can stand and hear seals without getting down on the ice. But Herzog stages the moment for its truth, how the evocative imagery of listening to ice suggests the sublime world on the other side. Herzog believes that truth can be fabricated through poetic and artistic choices like this one. As long as such creativity results in what Herzog sees as the truth of a scene, the method does not matter, even if his choices bend the documentary’s limits as a subdivision of nonfiction film.

Yet another interview features computer expert Karen Joyce, who carries on (and on) about her travels in exotic, dangerous locations. Even Herzog admits the interview “goes on forever,” though it speaks to the type of individuals that find themselves in Antarctica—people willing to face Nature no matter the risk. At the same time, Herzog establishes the continent as a place where humans do not belong; like visitors to the Moon, they are not meant to be there. Nonetheless, mysterious and deeply personal drives compel them, or maybe their journey South marks a sign of madness. In a later sequence, he draws an unspoken comparison between the people in Antarctica and a disoriented emperor penguin. A solitary penguin diverts his course from the others, heading inland toward the mountain, toward certain death. Herzog asks researcher Dr. David Ainley, “Is there such thing as insanity among penguins? I don’t mean that a penguin might believe he or she is Lenin or Napoleon Bonaparte, but could they just go crazy because they’ve had enough of their colony?” Could this madness be the very thing that drives people to attempt to overcome an unconquerable Nature?

Indeed, the madness of which Herzog speaks reveals another theme in Encounters at the End of the World—that of an impending apocalypse. In its madness, humanity attempts to conquer Nature and, as a result, slowly destroys the planet. Herzog’s respect for Nature aligns with the scientists and other interviewees in the film, who, in many cases, are so appalled with humanity’s unique disrespect for Nature that they leave and escape to Antarctica; they reject humanity in favor of Nature. Herzog finds a profound, poetic truth in their choice to face the sublime. But his film also tries to establish that, as persistent humanity may be its attempts to conquer Nature, the natural world remains beyond our absolute control. Consider when he stands on the edge of a volcano with Dr. Clive Oppenheimer, and they discuss the inevitability of another extinction-level eruption that human beings are helpless to prevent. “Human life is part of an endless chain of catastrophes,” Herzog explains, “the demise of the dinosaurs being just one of these events. We seem to be next.” Herzog’s remarks seem even more prevalent today, especially given Stephen Hawking’s recent prediction that humanity has less than a century left on this planet.

Indeed, the madness of which Herzog speaks reveals another theme in Encounters at the End of the World—that of an impending apocalypse. In its madness, humanity attempts to conquer Nature and, as a result, slowly destroys the planet. Herzog’s respect for Nature aligns with the scientists and other interviewees in the film, who, in many cases, are so appalled with humanity’s unique disrespect for Nature that they leave and escape to Antarctica; they reject humanity in favor of Nature. Herzog finds a profound, poetic truth in their choice to face the sublime. But his film also tries to establish that, as persistent humanity may be its attempts to conquer Nature, the natural world remains beyond our absolute control. Consider when he stands on the edge of a volcano with Dr. Clive Oppenheimer, and they discuss the inevitability of another extinction-level eruption that human beings are helpless to prevent. “Human life is part of an endless chain of catastrophes,” Herzog explains, “the demise of the dinosaurs being just one of these events. We seem to be next.” Herzog’s remarks seem even more prevalent today, especially given Stephen Hawking’s recent prediction that humanity has less than a century left on this planet.

Herzog seems to accept the transience of human beings, as though humanity’s short time on the planet equates to an astronaut’s brief mission on another world. (As Neil deGrasse Tyson noted on Cosmos, if time was represented by a Cosmic Calendar, the Big Bang would have taken place January 1, but humanity would have existed only for the last few seconds of December 31.) Herzog creates a further association when describing Antarctic scientists as astronauts exploring a sublime extraterrestrial landscape beneath the ice. Take his observations of Antarctic divers as they prepare their sub-temperature scuba gear: “To me, they were like priests preparing for mass,” he narrates. Or when the divers are under several feet of ice, “To me, the divers look like astronauts floating in space.” Later, he wonders, “And when we are gone, what will happen thousands of years from now in the future? Will there be alien archeologists from another planet trying to find out what we were doing at the South Pole?” Throughout the film, Herzog, like many of the scientists he interviews, accepts the inescapable disappearance of the human race.

However grim such notions may be, Encounters at the End of the World also treats Nature like a temple, evoking an almost spiritual, but certainly strange and inhuman kind of splendor. The film contains scenes that, through Herzog’s artistic use of his camera and the accompanying score, create cinematic poetry in its observations of Nature. During a five-minute underwater sequence without narration or interviews, Herzog’s choice of music implies the grandeur of what is shown. As a probing camera searches amid uncanny sea creatures rarely seen by human eyes, a folk song called “Planino, Stara Planino” echoes with ghostly Bulgarian voices, bringing a spiritual quality of other-worldliness to the Antarctic sea floor. With his inquisitive camera and music reverberating in unison over such scenes, the director creates a poetic association with the majesty of Nature that is felt throughout the film, whether it be sea life, volcanoes, seal sounds, or simply Pashov looking over the landscape.

However grim such notions may be, Encounters at the End of the World also treats Nature like a temple, evoking an almost spiritual, but certainly strange and inhuman kind of splendor. The film contains scenes that, through Herzog’s artistic use of his camera and the accompanying score, create cinematic poetry in its observations of Nature. During a five-minute underwater sequence without narration or interviews, Herzog’s choice of music implies the grandeur of what is shown. As a probing camera searches amid uncanny sea creatures rarely seen by human eyes, a folk song called “Planino, Stara Planino” echoes with ghostly Bulgarian voices, bringing a spiritual quality of other-worldliness to the Antarctic sea floor. With his inquisitive camera and music reverberating in unison over such scenes, the director creates a poetic association with the majesty of Nature that is felt throughout the film, whether it be sea life, volcanoes, seal sounds, or simply Pashov looking over the landscape.

Herzog is viewed as ultra-serious and sometimes dismissible for his strangeness, perhaps because his style has become ironically funny and self-referential in pop-culture (he parodied Encounters at the End of the World by voicing an Antarctic documentarian in DreamWorks Animation’s The Penguins of Madagascar). His oddball celebrity status has left the importance of his documentaries—their artistry, their commentary on the human-Nature struggle, their sheer beauty—somewhat overlooked. Nevertheless, there is a poetry to the dismal outlook and peculiarity of his documentaries, offering an ingrained point of view and way of understanding his films’ subjects. Certainly, viewers must appreciate Herzog’s imagination and way of looking at the world, and furthermore, appreciate the originality and naturalist’s insight he provides. From his perspective comes a willingness to recognize how human beings and Nature remain at odds, and through that, an attempt to understand our small place in the universe.

Sources:

Aimes, Eric. “The Case of Herzog Re-Opened.” A Companion to Werner Herzog. West Sussex: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2012, pp. 393-414.

Burke, Edmund. “A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful.” Aesthetics: A Comprehensive Anthology, Ed. Steven M. Cahn and Aaron Meskin. Malden: Blackwell Publishing, 2008, 113-122.

Cagle, Chris. “Postclassical Nonfiction: Narration in the Contemporary Documentary.” Cinema Journal. Vol. 52 Issue 1. 2012, pp.45-65.

Cronin, Paul. Herzog on Herzog. London: Faber and Faber Ltd., 2002.

Herzog, Werner. Conquest of the Useless: Reflections from the Making of ‘Fitzcarraldo’. Ecco, Reprint Edition, 2010.

LaRocca, David. “‘Profoundly Unreconciled to Nature’: Ecstatic Truth and the Humanistic Sublime in Werner Herzog’s War Films.” The Philosophy of War Films, David (ed. and introd.) LaRocca, UP of Kentucky, 2014, pp. 437-482.

Prager, Brad. The Cinema of Werner Herzog: Aesthetic Ecstasy and Truth. London: Columbia University Press, 2007.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review