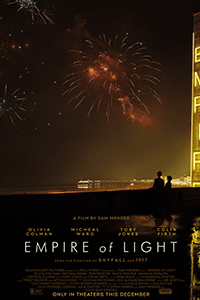

Empire of Light

By Brian Eggert |

An early scene in Empire of Light finds Stephen (Micheal Ward) and Hilary (Olivia Colman), two Empire Cinema employees in England’s coastal town of Margate, nursing a wounded pigeon. When Hilary shows Stephen the abandoned upstairs lobby on his first day, they find an injured bird in the dust and debris. Stephen demonstrates how to wrap the pigeon’s broken wing and then uses his sock to hold the wrap in place. Days later, they return upstairs and set the bird free. Writer-director Sam Mendes uses this scene to anticipate the relationship between Stephen and Hilary, both wounded in their ways, in need of healing, and yearning for freedom. Mendes’ unsubtle symbolism extends to the title as well. Empire of Light takes place around the vintage moviehouse, where a beam of light flickers on a screen and illuminates an entire world into which moviegoers can escape. Using the metaphor of light that creates motion and life out of celluloid moving at 24 frames per second, Mendes portrays life as a series of events, escapes, and detours. If his themes remain obvious, Mendes at least directs some excellent performances in a film that often looks pristine.

Mendes sets his film in 1981, just as Britain endures a struggling economy, a shift toward Thatcherism, and a surge of racial violence. The future seems bleak, and the Empire Cinema is past its prime—echoing the state of today’s culture and movie theaters. Two of the cinema’s upper auditoriums and elaborate bar area have long since been closed and left to the pigeons. In this downtrodden backdrop, Mendes centers at first on Hilary, a duty manager who oversees the theater’s staff, including the assistant Neil (Tom Brooke) and purist projectionist Norman (Toby Jones), for their embittered manager, Mr. Ellis (Colin Firth). Hilary lives a solitary life and shows no genuine interest in movies, having been placed at the theater by social services after a breakdown and hospitalization, the details of which go unshared. Occasionally, Mr. Ellis, a married man, asks Hilary into his office for a pathetic handjob. It’s a bleak existence, and Hilary floats through life in a Lithium haze until Stephen, a new employee, arrives and gradually takes to her openness.

And so, the two outsiders—the middle-aged woman plagued with mental illness and the young Black man regularly harassed by skinheads—form an unlikely and, in this setting, taboo romance. And not without consequences. For instance, their affair makes Hilary happy, so she stops taking her medication, leading to a chemical imbalance, followed by a memorable bipolar outburst at the theater’s gala premiere of Chariots of Fire—an event that means everything to Mr. Ellis. It must be said that Colman does sublime work here, capturing radiant happiness in Hilary’s highs and a cavernous emptiness in her lows. When the character becomes unhinged, the scenes recall Colman’s best moments in The Favourite (2018), with Hilary alluding to a traumatic upbringing and experiences with men. When Hilary fades into her illness, the film gradually shifts to Stephen’s perspective. But Ward’s role is less developed and expressive, even after the film occupies his subjectivity in the second half.

Fortunately, the cinematography by Roger Deakins makes Empire of Light worth the price of admission. This marks the fifth collaboration between Mendes and Deakins, a partnership that started with 2005’s Jarhead, and it’s their most nuanced work together, apart from Revolutionary Road (2008). Although Mendes occasionally offers a scene of painterly grandeur, such as rooftop New Year’s Eve fireworks punctuated with a kiss, he more often restrains himself to the downcast goings-on inside the old theater—sweeping up popcorn, selling candy, and laughing about the weirdest things left by moviegoers. Tonally, the film has a leisurely yet regal pace, unfolding with all the majesty of an Oscar-hungry prestige picture. It’s also a quiet film, accented by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross’ at once haunting and airily light score—their second this year after Luca Guadagnino’s Bones and All.

Fortunately, the cinematography by Roger Deakins makes Empire of Light worth the price of admission. This marks the fifth collaboration between Mendes and Deakins, a partnership that started with 2005’s Jarhead, and it’s their most nuanced work together, apart from Revolutionary Road (2008). Although Mendes occasionally offers a scene of painterly grandeur, such as rooftop New Year’s Eve fireworks punctuated with a kiss, he more often restrains himself to the downcast goings-on inside the old theater—sweeping up popcorn, selling candy, and laughing about the weirdest things left by moviegoers. Tonally, the film has a leisurely yet regal pace, unfolding with all the majesty of an Oscar-hungry prestige picture. It’s also a quiet film, accented by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross’ at once haunting and airily light score—their second this year after Luca Guadagnino’s Bones and All.

The structure of Mendes’ screenplay, his first solo effort, flows from one subplot to the next, from one protagonist to the next, in a manner that sometimes feels ponderous or unfocused. Even so, Mendes offers a throughline in the form of a love letter to cinema. As Norman, Jones’ sincere and rhapsodic speeches about the magic of light and the “illusion of life” on the big screen will make cinephiles swoon. Eventually, when Hilary resolves to take Stephen’s advice and finally watches a film, she leaves the choice up to Norman. In an obvious and inspired pick, Norman selects Hal Ashby’s Being There (1979), a film about a passive protagonist detached from his life and reality. But by the final frames, with its reverent voiceover (“Life is a state of mind”), Hilary brims with joy—and Mendes captures the moment in that all-too-common (but no less effective) shot of a delighted face in the darkened theater and a projector flickering overhead, recalling similar scenes ranging from Cinema Paradiso (1988) to Hugo (2011).

Empire of Light offers yet another 2022 film rooted in nostalgia and the wonder of cinema, told by a filmmaker making a personal statement. Mendes’ picture is less successful than Steven Spielberg’s The Fabelmans in conveying the transportive nature of going to the movies, and his remarks on race resonate less than those in James Gray’s Armageddon Time. Ultimately, the film’s feelings about the equalizing power of art, from cinema to two-tone music (Stephen’s favorite multicultural genre that combined punk and new wave with Jamaican reggae and ska), and its ability to supply a necessary escape in hard times are afterthoughts, if blatantly emphasized. Ultimately, the film seems to be more about people who learn to connect despite their differences, and they’re portrayed by the cast and captured on camera by Deakins with great care and affection. Although Empire of Light feels like it’s trying too hard to make a grand statement on the power of art in a serious mode to win Oscars, I could not resist the humanity and beauty on display.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review