Emma.

By Brian Eggert |

Will Jane Austen adaptations ever have another renaissance like the one experienced in 1995? Ang Lee’s Sense and Sensibility set the standard impossibly high that year, achieving an uncommonly human touch to Austen’s idealistic tale of romance and class hierarchies, with a cast that today seems impossibly good (Emma Thompson, Alan Rickman, Kate Winslet, Hugh Grant, Hugh Laurie, Imelda Staunton, and Tom Wilkinson). But Masterpiece Theater’s Roger Michell and his version of Persuasion also raised the bar, blending a naturalistic romance with a period-accurate milieu and performances by Amanda Root and a dashing Ciarán Hinds. Then there’s the BBC’s sweeping six-episode miniseries, Pride and Prejudice, featuring Jennifer Ehle and Colin Firth in roles bound to make any viewer’s heart ache and swoon. Of course, the back-to-back adaptations of Emma have left their mark not through their faithfulness to the original text but their novelty. Amy Heckerling’s Clueless took the story to Beverly Hills, resulting in a quintessential 1990s film that still brims with energy, wit, and genuine emotion—it may be the best modern-day adaptation of Austen yet (it also inspired this reader to explore Austen’s written work). A year later, Gwyneth Paltrow made a sprightly turn in a version of Emma set against the original 19th-century backdrop.

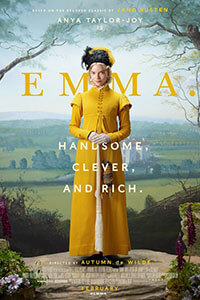

Not surprisingly, filmmakers have avoided trying to improve upon these adaptations in the subsequent decades, save for inspired films by Joe Wright or Whit Stillman. And with classical book-to-screen adaptations thoroughly covered between these 1995 works and episodic versions on British television, we’re left with postmodern and ironic perspectives on Austen, the stuff of Pride and Prejudice and Zombies (2016) and Autumn de Wilde’s new version of Emma (or depending on how literal you take the poster, EMMA., punctuation and capitalization intended). De Wilde, a photographer and music video director, makes her feature-film debut in this mannerist piece, complete with elongated necks and accentuated pastels captured by Christopher Blauvelt’s cinematography. She brings her stagey lighting and ostentatious costume design to Austen’s most un-self-aware protagonist, a character who proves too superficial and materialistic for some readers. De Wilde’s mannerist visual approach won’t help endear the character to skeptics, as the film shows evidence of a director more interested in design, style, and particulars of performance than the substance and emotions at work in Austen’s story.

De Wilde’s style-first emphasis cannot help but resemble the worlds created by Sophia Coppola in Marie Antoinette (2006) or various examples from Wes Anderson’s career, where the artificiality of the production offers a commentary through its visual luster. For instance, Emma employs seasonal chapters, each introduced in a stationary image reminiscent of the stage-like transitions in Anderson’s Rushmore (1998). Even Blauvelt’s symmetrical framing and sharp camera movements resemble an Anderson picture, while the editing by Nick Emerson uses abrupt cuts to punctuate a joke or accentuate the affectations of de Wilde’s style. Costumer Alexandra Byrne, along with makeup and hair designer Marese Langan, employ rigid and indulgent designs that keep the viewer at a distance, from unruffled gowns to the mass of tight spirals in Emma’s hair. The approach makes Austen’s text seem like a storybook illustrated by designers, a romantic fantasy within a romantic fantasy. It’s an aesthetic that is not without its critiques of Emma Woodhouse’s classist world and all its frivolities, but barbs so beautifully rendered will hardly break the skin.

Austen’s most snobbish, 20-year-old protagonist is introduced to us as “handsome, clever, and rich,” played by Anya Taylor-Joy in a role that makes use of the performer’s painterly features, as if she were realized by Jacopo Pontormo. She’s first seen accompanied by her two manservants, drifting around the Highbury estate owned by her hilariously hypochondriacal father (Billy Nighy, in full Bill Nighy mode) before dawn, picking flowers—or rather, ordering her attendants to pick them by lantern light. Her tedious and embellished life is characteristic of the period (Austen published her novel in 1815), full of manners and elegance to spare, enough to describe the entire society as ornamentation. De Wilde’s film follows Austen’s novel, preoccupying Emma with matchmaking after her longtime governess and friend, Miss Taylor (Gemma Whelan), gets married and leaves her to find a new project. She sets out to arrange a husband for her less fortunate friend, Harriet (Mia Goth), without any real understanding of what Harriet desires.

Austen’s most snobbish, 20-year-old protagonist is introduced to us as “handsome, clever, and rich,” played by Anya Taylor-Joy in a role that makes use of the performer’s painterly features, as if she were realized by Jacopo Pontormo. She’s first seen accompanied by her two manservants, drifting around the Highbury estate owned by her hilariously hypochondriacal father (Billy Nighy, in full Bill Nighy mode) before dawn, picking flowers—or rather, ordering her attendants to pick them by lantern light. Her tedious and embellished life is characteristic of the period (Austen published her novel in 1815), full of manners and elegance to spare, enough to describe the entire society as ornamentation. De Wilde’s film follows Austen’s novel, preoccupying Emma with matchmaking after her longtime governess and friend, Miss Taylor (Gemma Whelan), gets married and leaves her to find a new project. She sets out to arrange a husband for her less fortunate friend, Harriet (Mia Goth), without any real understanding of what Harriet desires.

Both de Wilde’s direction and the screenplay by novelist Eleanor Catton present Emma with an expressive arch quality that underlines the main character’s preening, undue self-assuredness. It’s a take that makes Emma a character perfectly relevant for our social media-obsessed age, where every seemingly generous post has a self-serving intent. It’s anyone’s guess why the intelligent and decent Mr. Knightley (Johnny Flynn), a family friend with prospects, falls for Emma with her occasionally awful, vain, indelicate, and inconsiderate behavior. Case in point: Her cruel treatment of the genuine and vulnerable chatterbox Ms. Bates (Miranda Hart), to whom Emma never adequately apologizes in this version, might render the character finally unsympathetic. It’s difficult to root for this Emma because it’s as though Cher from Clueless had been replaced by Regina from Mean Girls. She’s too superior and persnickety, and everyone puts up with her because she’s rich. Our affection for the character only emerges through Mr. Knightley’s love—making for an admittedly swoon-worthy finale, nosebleed and all—but that may not be enough to endear her to some viewers.

Much of the film depends on whether we can look beyond the superficiality of de Wilde’s style, the rigid formality of David Schweitzer and Isobel Waller-Bridge’s score, the extravagance of the designs, and be overcome as Emma’s best-laid plans crumble. It’s commendable that de Wilde challenges the viewer with these formal barriers, expecting that we will see beyond them to recognize the romantic undercurrents that become so pronounced by the final scenes. Alas, these aesthetic choices render Emma a brazen and sometimes hollow experience, more concerned with getting the look right than the emotions. As a result, de Wilde’s take on the material acknowledges that Emma’s world is one of surfaces, but she doesn’t delve beyond those surfaces enough to explore the characters internal lives in the way Austen did with her prose or as previous iterations did with expository devices (such as narration or a diary). What we’re left with, then, is an empty, if impressively mounted satire on class that engages our eyes but not our hearts.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review