Emilia Pérez

By Brian Eggert |

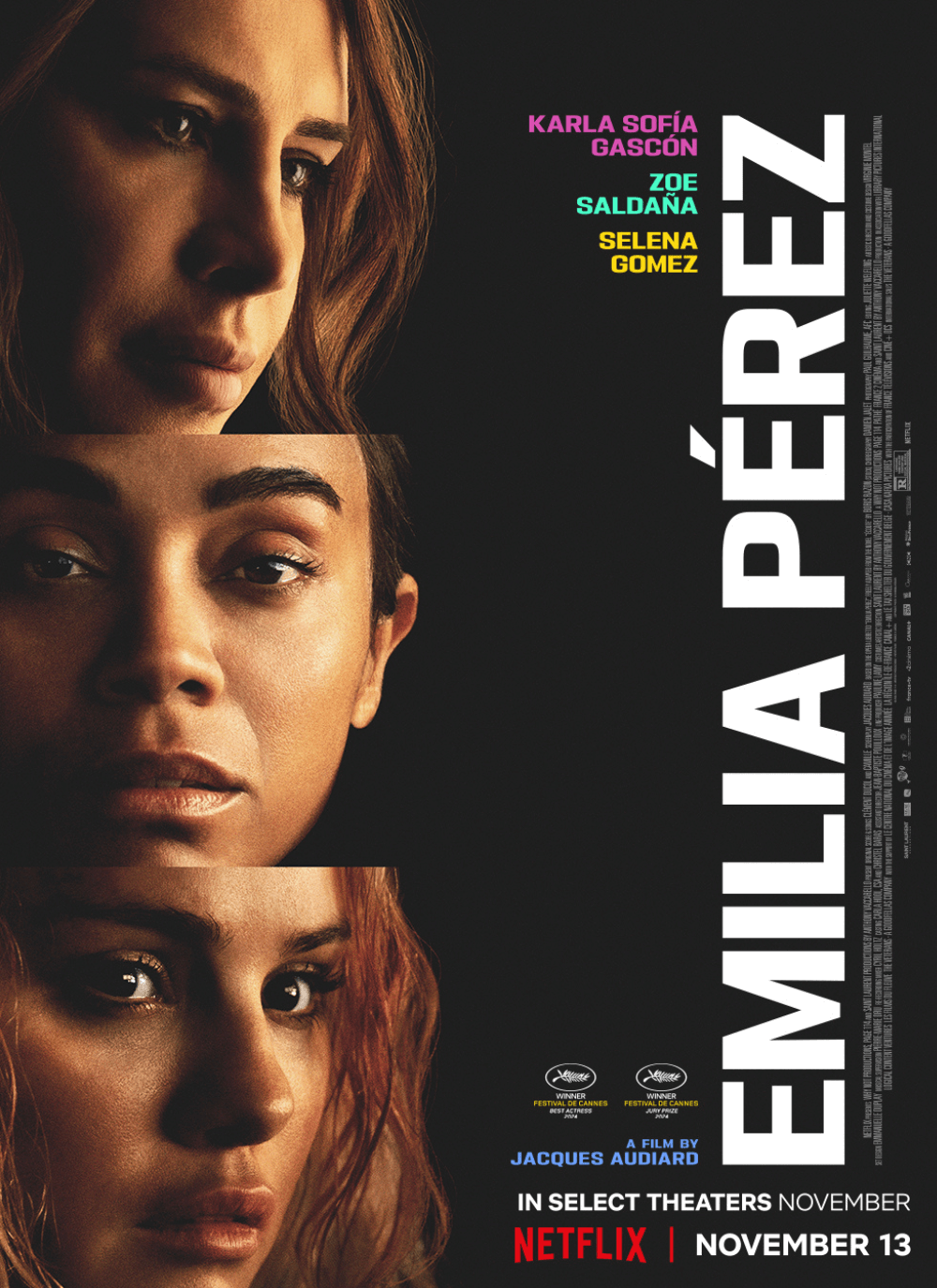

A film can be imperfect but still deserve love and achieve greatness. Take Jacques Audiard’s new project for Netflix, Emilia Pérez, as a case in point. This divisive, pop-inspired tragedy about the identity and redemption of a Mexican drug cartel head takes such bold swings that I found it irresistible. The French auteur’s latest is an audacious, genre-defying, tonally shifting musical that takes on female empowerment, political corruption, gender-affirming surgery, and human plurality—as well as transitioning into one’s true self, making amends for past crimes, and getting answers for the staggering number of cartel-related disappearances in Mexico. All of this might sound like unlikely material for a musical, but then again, so are the Weimar Republic, sex work, and murderers who turn their victims into pies, but that hasn’t stopped these ideas from becoming iconic musicals. Instead, the inherent messiness of people emerges as a theme in Audiard’s narrative and execution. Emilia Pérez isn’t a ritzy MGM musical produced during Hollywood’s Golden Age; it’s a rough-around-the-edges production with delightfully unpolished song-and-dance sequences. But like its titular character, the flawed yet endearing result earned my affection and awe.

Drawing from a brief thread in Le Monde contributor Boris Razon’s 2018 novel Écoute, Audiard’s screenplay explores the fluidity of identity. He centers on a gravely voiced Mexican drug lord, Manitas del Monte, who resolves to leave his criminal life and embrace the woman he has felt inside him since childhood. Under facial prosthetics, Manitas is played by the mesmerizing Karla Sofía Gascón, who shared the Best Actress award at the film’s Cannes Film Festival debut with her costars, marking the first such award for an openly trans actress. Gascón is empathetic, wounded, and passionate in the role, but she’s also a force of danger. With her character, Audiard forgoes turning Emilia Pérez into a film with something to say about transgender identity, like The Danish Girl (2015). Instead, it’s a personal and specific account, and its methods of representing the trans experience may not always conform to the inclusive discourse or socially conscious language of the moment. But it does something better: it tells a story that revolves around a trans character who’s moving and involving, which helps normalize a socially and systemically marginalized group.

Our entry point is Rita (Zoe Saldaña), a Mexico City attorney worn out from the rampant corruption in her office, the ignorance of her boss, and getting little in return for her effort. In the opening song, she announces the story to come as a tale of love, death, and the suffering of a country, firmly establishing Emilia Pérez as a tragedy. After her team wins a highly publicized case, she receives a mysterious call from a man promising to make her rich. Veritably kidnapped, Rita soon comes face-to-face with Manitas, who promises to pay millions if she coordinates specialists to carry out the required procedures in secret. After flights to Bangkok and Tel Aviv, Rita arranges the operations and a new home for Manitas’ wife, Jessi (Selena Gomez), and their two children in Switzerland. At the same time, the cartel leader’s death is staged, and the newly dubbed Emilia Pérez emerges, funded by years of running drugs and making people disappear. Several years later, Emilia meets Rita again, and together, they establish an NGO dedicated to unearthing the bodies of Mexico’s missing persons and giving their loved ones closure, many of them murdered during Manitas’ reign.

Audiard’s musical concentrates on storytelling over razzle-dazzle, embracing the genre’s impulsive nature without feeling chaotic. Emilia Pérez features long passages without songs, and the performative numbers themselves, while catchy, don’t overshadow the narrative thrust. The music and songs, credited to composer Clément Ducol and singer Camille, range from hip-hop to operatic in genre, often with a Latin sound and performed in Spanish. Yet, the choreography by Damien Jalet proves less expressive and far removed from a traditional musical presentation. Only the sequence for “La Vaginoplastia,” a song about the surgeries required to complete a transition, attempts the playful (and, in this case, ironic given the subject matter) whimsy one often associates with musicals. For the rest, the ordeal has a scrappy quality, mainly because these players don’t usually perform in this genre. But with the movie musical just barely present in modern cinema, who does? The days of performers such as Fred Astaire, Ginger Rogers, Judy Garland, and Gene Kelly, who specialize in musicals, have long since passed. Today, audiences are lucky to get one or two worthwhile musicals a year.

That’s why it’s surprising to see Saldaña, who steps away from actionized blockbusters for James Cameron and the MCU, showing she has the voice and sharp physicality for singing and dancing. Rita’s musical numbers are the most kinetic and alive in the film. By contrast, Gascón’s songs are performed with a sensitive voice, from Manitas’ rough but delicate vocals (“I want the depth of my soul to smell like honey”) to her airy singing as Emilia, with open-hearted lyrics. Her songs ache, particularly after her character transitions, and she begins living with Jessi and the kids under the pretense of Manitas’ cousin—all the while reminded of her former life. The tender song “Papa,” performed with her son (and sung by Juan Pablo Monterrubio), reflects Emilia’s inner turmoil and lingering aspects of Manitas, including a similar smell only her son can recognize. Gomez plays a more significant role in the film’s volatile final third, as Jessi, years removed from the father of her children, moves on to a passionate affair with Gustavo (Édgar Ramírez). But Emilia still feels possessive about her former spouse and family, leading to a pointed confrontation.

To whatever extent this material might feel unlikely for its director, its themes are more appropriate than the surface suggests. Audiard has a journeyman’s ability to switch from one genre to another, yet he maintains an auteur’s obsession with dramatic changes in his characters. That’s a persistent concern in his oeuvre: A Prophet (2009) found Tahar Rahim playing an outsider who finally discovers his calling as a kingpin in prison. Rust and Bone (2012) charted a similar shift in Marion Cotillard’s character, who goes from a theme park whale trainer to an underground fight manager. In Dheepan (2015), Audiard’s Palme d’Or winner, a Sri Lankan soldier wrestles with integrating his faux family into his new French surroundings. In Audiard’s English-language debut, The Sisters Brothers (2018), John C. Reilly’s Western outlaw dreams of settling down and living a quiet domestic life. In each example, Audiard confronts realistic subjects with poetic flourishes, and that tendency has never been more apparent than in Emilia Pérez, given the innate expressiveness of musicals. However, in his portrait of Emilia’s journey, it’s curious that Rita remains the focal point, as her inner life goes mostly unexplored, serving as a kind of participatory witness or audience surrogate to the tragic events that befall Emilia and Jessi.

The film’s detractors have raised questions about its authenticity—its portrait of the trans experience, life in Mexico, etc.—especially considering Audiard, who does not speak Spanish, shot most of the film on French soundstages and put a Spanish woman and two Americans, but few Mexicans, in the lead roles. The major exception is Adriana Paz, excellent, who plays Emilia’s lover, and shared Cannes’ Best Actress award with costars Saldaña, Gascón, and Gomez. However, little about the musical genre is meant to be an authentic slice of reality. Realism and musicals are antithetical. When characters break into songs at random, and crowds dance alongside the main characters, this is less a reflection of reality than a conscious use of subject matter usually reserved for unvarnished realism to put a new spin on the musical. Rather, Audiard’s Almodóvarian premise and playful execution of Emilia Pérez coalesce into a grim fantasy of change and absolution wrapped in a gritty drama and theatrical tragedy. Its unique blending of tones, styles, and genres into an unclassifiable work of art makes Audiard’s film exciting, entertaining, and affecting. Much like the eponymous character, the film doesn’t fit into any box or prescribed definition, and that’s what makes them so defiantly original.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review