Emancipation

By Brian Eggert |

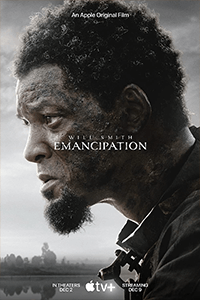

Caught between two modes, the Oscar-baiting prestige drama and an exploitative action movie, Emancipation never finds a balance. Director Antoine Fuqua helms a competent and sharp-looking production alongside producer-star Will Smith. But the result often feels like a by-the-numbers historical epic, with all the requisite speeches, slow-motion, and sweeping battle scenes. Yet, somewhere between the obvious script and Smith’s ill-fitting ultramodern screen presence, Fuqua cannot resist turning the subject matter into a story dependent on chases, violence, and warfare over characters or emotions. Written on spec by William N. Collage, the film’s screenwriter—known for duds such as Exodus: Gods and Kings (2014) and Assassin’s Creed (2016)—based the material on the true story of a man named Gordon, who escaped slavery and joined the Union Army. A famous photo of Gordon’s unthinkably scarred back would be used by the abolitionist movement as proof of slavery’s horror. Smith plays Gordon, here renamed Peter for some reason. From this freely adapted chapter in history, Emancipation uses its reported $120 million budget to offer a dry and uneven retelling of an otherwise harrowing story.

Opening titles situate the film just after the Emancipation Proclamation when enslaved people faced a choice: wait for their liberation or take freedom for themselves. However, before Peter knows anything about his options, the Confederate army buys him to build a railroad—and he vows to someday return for his plantation-bound wife (Charmaine Bingwa) and children. Soon, Peter and a few others learn of their newly declared freedom and resolve to escape through dangerous swampland toward “the sound of Lincoln’s cannons” in Baton Rouge. The lofty filmmaking in these early scenes suggests a serious costume drama, punctuated when Fuqua depicts unflinching scenes of cruelty and murder perpetuated against the enslaved Black men. Later, these scenes haunt Peter as he fights for survival. But the film’s violence—compelled by Peter’s unwavering Christian beliefs that function as a shield, or perhaps a dagger since Peter kills a pursuer with a crucifix—operates with the logic of the Blaxploitation slave-revenge subgenre. Fuqua’s genre-inflected setups suggest he would have rather been making something pulpier, or at least another Equalizer sequel (his next project, incidentally), and they clash with the film’s stately tone.

Even so, Emancipation leans into action movie tropes by giving our hero a villain, Fassell (Ben Foster), a dreaded “manhunter” accompanied by his right-hand crony, Sergeant Howard (Steven Ogg, who played second fiddle to Negan on The Walking Dead). Foster, who excels at playing antagonists, turns Fassell into a B-movie version of Michael Fassbender’s plantation owner in 12 Years a Slave (2012). Foster chews scenery and delivers villainous dialogue like a pro, making the character appropriately detestable. When Peter escapes, Fassell announces, with insidious pleasure in his voice, “We’ve got work to do.” What unfolds is a tense, days-long chase through the swamp, where, in a touch of unintentionally hilarious sensationalism, Peter must wrestle an alligator with a knife underwater to survive (between Damien Chazelle’s Babylon and Ti West’s X and Pearl, it has been a big year for alligators in cinema). The film’s unsuccessful blend of actionized suspense and gravity recalls Kasi Lemmons’ Harriet Tubman chase movie, Harriet (2019), a similar misstep.

Emancipation resists digging beyond the surface irony that, after escaping enslavement in the South, the liberated Peter is dubbed stolen property or “contraband” by the North, and he’s forced to enlist and to “get back at those God-forsaken devils.” Why confront complex hypocrisies head-on, especially when there’s a battlefield sequence to mount? After all, Gordon did go from slave to soldier in a matter of weeks, so at least it’s not a Hollywood fabrication (even though the dramatic turn feels like one). Fuqua reaches an underwhelming climax with scenes reminiscent of Edward Zwick’s Glory (1989), with Black soldiers fighting for their freedom in the Union Army. Although the scenes lack tension, at least cinematographer Robert Richardson knows where to place the camera. But the filmmakers’ choice to desaturate every image, draining much of the color to create the look of a sepia-toned photograph (similar to the look of Women Talking), gives Emancipation a faux visual historicity. Along with the film’s slow-motion and grandiose compositions for big moments, Fuqua attempts an epic stature that never lands.

Emancipation resists digging beyond the surface irony that, after escaping enslavement in the South, the liberated Peter is dubbed stolen property or “contraband” by the North, and he’s forced to enlist and to “get back at those God-forsaken devils.” Why confront complex hypocrisies head-on, especially when there’s a battlefield sequence to mount? After all, Gordon did go from slave to soldier in a matter of weeks, so at least it’s not a Hollywood fabrication (even though the dramatic turn feels like one). Fuqua reaches an underwhelming climax with scenes reminiscent of Edward Zwick’s Glory (1989), with Black soldiers fighting for their freedom in the Union Army. Although the scenes lack tension, at least cinematographer Robert Richardson knows where to place the camera. But the filmmakers’ choice to desaturate every image, draining much of the color to create the look of a sepia-toned photograph (similar to the look of Women Talking), gives Emancipation a faux visual historicity. Along with the film’s slow-motion and grandiose compositions for big moments, Fuqua attempts an epic stature that never lands.

Much of the film’s unevenness is due to Smith’s characteristically modern presence; he neither disappears into the role nor into the setting. Peter may be a single-note character because Collage wrote him that way, but he also looks like Smith putting on a performance. Whether audiences want to watch Smith after the infamous Oscar slap is another issue altogether. Some critics have framed Emancipation as Smith’s comeback vehicle, ignoring that the film wrapped principal photography in New Orleans in late 2021, long before Smith struck Chris Rock on live television in March 2022. But the awards-hungry film isn’t likely to help Smith’s reputation or anyone else involved. Along with Peter, most characters remain dimensionless, leaving the narrative to consist of one plot event after another. The exception is Foster, who is memorably vile, but it’s nothing new for him; he’s been playing deranged villains since 3:10 to Yuma (2007), and what’s more, he’s gone from the film far too early.

Emancipation exists in a curious in-between space. Regardless of Fuqua’s tendency to look at his subject matter through an actionized lens, he never trivializes the material. Yet, he also doesn’t make the story feel particularly heartrending or urgent. Somehow, he delivers a respectable, flavorless movie about a traumatic historical account that should reverberate today—but it doesn’t. Had the filmmakers tipped the scale toward a more genre-centric approach, similar to Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained (2012), or a more humanistic touch as in 12 Years a Slave, the result may have been more potent and memorable. Unfortunately, Fuqua occupies a position between both extremes, never committing to one or the other, and therein never distinguishing his film in a way that gives it personality. Apart from an alligator fight and some underwhelming action, Fuqua takes few risks and asks little more of his audience than polite and unearned reverence.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review