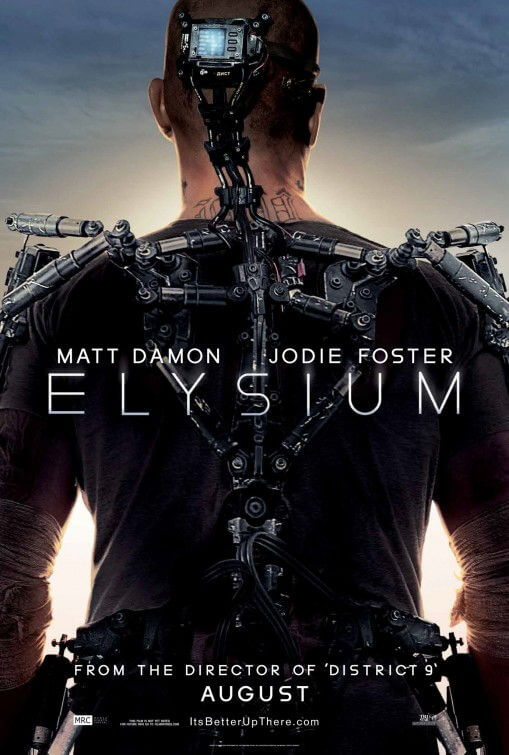

Elysium

By Brian Eggert |

Neill Blomkamp’s Elysium comes four long years after his breakthrough debut District 9, which was hailed by critics and genre aficionados as an instant science-fiction classic. With it comes the expectation that the South African writer-director will once again catch lightning in a bottle, that he’ll find that same balance of gritty escapist action, fascinating tech designs, and a sci-fi-infused political parable, all inside a surprisingly human narrative. And while each of those characteristics is present in Elysium, the result disappoints not only because it fails to meet our admittedly unrealistic hopes that it might live up to Blompkamp’s first, but because, ironically enough, the outcome isn’t as polished as his sophomore effort. Indeed, Blomkamp’s approach to storytelling has taken a similar journey as his move up—from a relatively low-budget project on District 9, which required so much ingenuity and resourcefulness, to the kind of underdeveloped, mindlessly big-budget Hollywood production audiences expect during summer movie season. But it’s best not to let expectation get the better of you; even if his second film’s social commentary isn’t as strong as his first, Blomkamp rarely produces a dull moment.

Set in the year 2154, the film opens on a dystopian Earth where human civilization has been divided into two classes. On the overpopulated surface festering with poverty and squalor reside the ultra-poor, who live in a seemingly endless landscape of shanty huts and try to survive with no medical care and barely a scrape of food. High above in orbit is Elysium, a massive utopian space station catering only to the super-rich who can afford to live in its decadence: clean air, green scenery, and free medical treatments for every conceivable ailment. The setup alone emphasizes the economic gap between classes and, just by association, impregnates Elysium with the illusion of a social commentary. But as Blomkamp’s film goes on, it becomes apparent the filmmaker is more concerned with the actionized possibilities of such a futureworld—including robots, space shuttles, and zap guns—than how his story might raise questions about its parallels to contemporary society.

Our hero is Max (Matt Damon), an ex-car thief and parolee whose former criminal life has been abandoned in favor of a quiet job at the robot factory. Pestered by his friend Julio (Diego Luna) to embrace his inner criminal and reminded of his good nature by his first love Frey (Alice Braga), a doctor with a daughter dying of leukemia, Max looks into the sky at Elysium and dreams of getting a ticket. He also drifts off through the film in overwrought flashbacks, remembering his childhood times with Frey at his side and the good Sister who told him he’d do important things someday. Sure enough, after an accident at work that leaves him irradiated, Max has five days to live, and a trip to Elysium’s advanced medical facilities is his only chance of survival. Dirt poor and with no options, Max agrees to a radical scheme concocted by Earthbound rebel Spider (Wagner Moura) to get aboard the heavenly space station and use its advancements for the betterment of the human race. The plan: shoot down the shuttle of billionaire robot factory owner John Carlyle (William Fichtner) and steal information stored in Carlyle’s brain that will allow Spider to gain access to Elysium and shut down its security. To keep Max going, Spider’s unsavory crew drills an exo-suit into Max’s body, making him a kind of cyborg superman.

If Max is Superman, then Delacourt (Jodie Foster) is Lex Luthor—the Secretary of Defense with a bleach-blonde hairdo and the odd accent of a Frenchwoman taught to speak English by a Brit. She’s tasked with making certain no filthy Earthlings get aboard and contaminate the betters, but she seems to hate Earth so. Why? What drives this hatred beyond the usual excuse of pure elitism? We never find out. She’s a prickly character that, given some background and juicier dialogue, could have been something like Angela Lansbury in The Manchurian Candidate. Instead, she’s left to utter silly villain lines that at times raise questions of logic. (To make a point about how protective she feels over her space station, Delacourt asks Elysium’s president if he has any children. Wouldn’t she know this, being the Secretary of Defense? Wouldn’t everyone on Elysium know if the president has children?) Also underdeveloped is Delacourt’s henchman, Kruger (Sharlto Copley), a decommissioned soldier and sword-wielding madman she uses to carry out her under-the-radar deeds. She tasks Kruger with stopping the raid on Elysium, but Kruger’s unpredictable streak leads to violence both on Earth and, eventually, on the space station itself.

Strangely, Blomkamp spends little screen time developing Elysium and its population. Scenes on the station mostly involve Delacourt’s plans to “retire” the current president by scheming with Carlyle to reboot Elysium or something like that. Its residents dress and eat well, their homes are clean and pointedly white, but there’s no personality to the place aside from tedious serenity. Whereas District 9 considered both sides of the alien and human apartheid in South Africa, Blomkamp seems content to demonize the privileged and root solely for the underclasses. This setup means the stakes are outlined in a few simple broad strokes, no more complicated than black and white, human and alien, or in this case, Earthling and Elysian. The conflict is clear, the good guys are good, and the bad guys are bad, nothing more or less. Enduring and good-humored, Max would be boring if Damon were not such a likable actor. Foster’s character is, as suggested, frustratingly underdeveloped. Copley is the standout as the wildly sadistic Kruger, the kind of character whose face is blown off by a grenade but he keeps coming at you; yet, he too is grossly under-motivated.

All of these characters and situations are serviceable and entertaining, however. Making it even easier to sit back and enjoy the ride is Blomkamp’s mise-en-scène, comprised of exciting action scenes, coarse hand-to-hand combat, explosive weaponry, and a vérité visual style. He saturates every frame with sensory information that makes us feel the story, from the visual stink of the squalid Earth slums to the fragrant promise of cherry blossom trees planted about the structural coldness of Elysium’s core. Blows exchanged between the robo-enhanced Max and, in time, Kruger, look painful, their impact hard and reminiscent of the visceral quality in a Paul Verhoeven picture, though at times, it feels as if Blomkamp rushes us through the action with sometimes abrupt cutting. High-tech guns and protective shields look intimidating and deliver a physical pummeling we feel in the film’s shocking degree of bloodshed, fully justifying the R-rating. In fact, Elysium’s entire second half or more plays like an extended reel of those thrilling few minutes from District 9 where Copley’s infected government employee teams with an alien to escape a maximum security detention center using gory alien weapons.

Blomkamp seems to revel in these moments; so do the satisfied groans in the audience. As such, it’s difficult to come down too hard on Elysium for what it lacks in political edge, since the visceral quality of the film has been so carefully detailed. We must remember that this is only the promising director’s second picture, and as a result, we’re still trying to determine what “a Neill Blomkamp film” should mean. Whether he keeps making inspired action movies or high-toned science-fiction, his talent behind the camera is evident. And so, Elysium belongs on the ever-growing list of 2013 science-fiction titles better seen for their production design and mindless action than their story or characters. Oblivion, Pacific Rim, Man of Steel, Europa Report, After Earth, The Host, and even Star Trek Into Darkness have all provided more style than substance. Each title on this list (and there were others not mentioned) seems to value concepts over fully formed ideas, and intriguing setups over significant narrative arcs. Nearly all of them were impressive in their technical specs and formal presentations, but none will be remembered for ages as essential sci-fi. For its merits and effortless escapism, Elysium will at least be remembered as a solid actioner.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review