Elvis

By Brian Eggert |

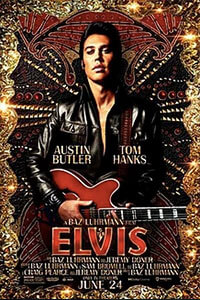

From the kaleidoscopic, gem-encrusted opening to the adulatory end titles that celebrate Elvis Presley as the best-selling solo artist of all time, Baz Luhrmann’s biopic turns the dial to 11 for over two-and-a-half hours. Tackling The King, arguably the most iconic figure in popular music history, presents an impossible task of condensing his larger-than-life persona and lasting mythology into a feature film. Luhrmann approaches the challenge of Elvis with the same frenetic energy as other iconic subjects covered in his Romeo + Juliet (1996) and The Great Gatsby (2013)—by rushing headlong into an eye-popping, head-spinning array of jam-packed montages, vivid camera movements, and anachronisms characteristic of the director’s ostentatious style. Anything less than hyper-stylized and it simply wouldn’t be “a Baz Luhrmann film.” However, the story amounts to little more than the obligatory dramatic beats of any musician biopic, such as Walk the Line (2005) and Bohemian Rhapsody (2018)—Elvis’ rural beginnings lead to artistic inspiration, a meteoric rise, the curse of fame, drug abuse, and eventual downfall. Ultimately, the film is a mixed bag of highs and lows, and precisely what you might expect from Baz Luhrmann’s treatment of this or any subject.

Among the most prominent and surprising lows is the usually reliable Tom Hanks, playing Colonel Tom Parker behind some unconvincing practical makeup and an accent (Deep South by way of the Netherlands) that confuses the ears. Hanks never disappears into the role, so Parker always looks like Hanks in a fat suit with a hooked rubber nose. Worse, the screenplay, credited to four writers (Luhrmann, Sam Bromell, Craig Pearce, Jeremy Doner), relies on Parker’s omnipresent narration. The entire film unfolds from Parker’s perspective, making Elvis an outsider in his own story—and sized up from Parker’s perspective in his last days, wandering around Las Vegas casinos with an IV drip. In a flurry of gleaming images, zippy transitions, and 360-degree camera spins, Luhrmann shows us that Parker is a lifelong schemer who started as a circus promoter before advancing into country music under his All-Star Jamboree Attractions label. A bloated, serpentine figure armed with an assortment of absurd cane heads, his sole ambition seems to be finding the ultimate “snow job,” meaning he wants to dupe people into giving the maximum amount of money while leaving them happy about it. Parker eventually finds Elvis. But he never loses that circus mindset, so Elvis becomes Parker’s ultimate freak show attraction.

While Hanks’ persistent and downright bizarre voiceover repels, Austin Butler’s impressive turn as Elvis presents the film’s high point, drawing our gaze through Parker’s eyes. “Greasy hair, girly makeup,” reflects Parker, “I cannot overstate how strange he looked.” If Hanks appears exaggerated behind his cartoonish nose, double-chin, and paunch, Butler’s natural features (wax lips, high cheekbones, ice-blue eyes) look equally distorted. Still, Butler nails Elvis’ buttery voice and signature rubber-legs wiggle, the overall effect of which leaves teenage girls overcome with desire. Parker watches one girl from backstage and sees her driven to scream by some unknown force inside—a feeling “she was not sure she should enjoy.” Parker recognizes that Elvis is “forbidden fruit” and the ideal attraction: “Something they want to see, but some part of them thinks it’s wrong.” Dollar signs practically appear in the Svengali’s eyes as he witnesses a crowd come undone and throw panties on the stage. “I watched that skinny boy in the pink suit transform into a superhero,” Parker narrates, and then sets out to exploit his show horse for all he’s worth.

While Hanks’ persistent and downright bizarre voiceover repels, Austin Butler’s impressive turn as Elvis presents the film’s high point, drawing our gaze through Parker’s eyes. “Greasy hair, girly makeup,” reflects Parker, “I cannot overstate how strange he looked.” If Hanks appears exaggerated behind his cartoonish nose, double-chin, and paunch, Butler’s natural features (wax lips, high cheekbones, ice-blue eyes) look equally distorted. Still, Butler nails Elvis’ buttery voice and signature rubber-legs wiggle, the overall effect of which leaves teenage girls overcome with desire. Parker watches one girl from backstage and sees her driven to scream by some unknown force inside—a feeling “she was not sure she should enjoy.” Parker recognizes that Elvis is “forbidden fruit” and the ideal attraction: “Something they want to see, but some part of them thinks it’s wrong.” Dollar signs practically appear in the Svengali’s eyes as he witnesses a crowd come undone and throw panties on the stage. “I watched that skinny boy in the pink suit transform into a superhero,” Parker narrates, and then sets out to exploit his show horse for all he’s worth.

With Luhrmann telling the story from Parker’s point of view, we never get a clear understanding of Elvis or what goes on in his head—as though the director acknowledges his own exploitation of Elvis’ iconography to propel this film. And propel he does, with all the energy of a movie trailer selling Elvis’ life, including kooky angles, animated titles, cartoon flashbacks, split-screen montages, and aspect ratio changes. Luhrmann barrels through the story, never getting to the core of why Elvis remains so devoted to Parker. In short order, the manager becomes a surrogate for Elvis’ late mother (Helen Thomson) and ineffectual father and business manager (Richard Roxburgh). And he continues to pull Elvis’ strings, even after the singer realizes the two aren’t aligned. Parker wants him to adopt the look of a “clean-cut American boy” because his black leather and gyrating hips upset conservative politicians, prompting accusations that Elvis commits “crimes of lust and perversion.” But Elvis wants to let his freak flag fly. Luhrmann dwells on this enduring conflict between Elvis and his manager to the extent that his film should have been called “Elvis and Parker.”

Meanwhile, Luhrmann glosses over events that would seem to be important to Elvis, but because they’re not significant to Parker, they don’t earn much screentime—accentuating the oddity of Luhrmann’s storytelling choice. Elvis seems to meet Priscilla (Olivia DeJonge), father Lisa Marie, and become estranged from both within a few minutes of screentime. The same goes for Elvis’ Hollywood career. None of it registers on an emotional level. Instead, Luhrmann underlines Elvis’ controversial role in American culture, including a pulpy flashback to his childhood that shows how gospel and blues influenced the singer’s sound. For Luhrmann, Elvis’ amalgamation of musical styles becomes a symbol of racial desegregation, but Parker doesn’t care about such things—he just wants to sell tickets to the show. The political battlefield reaches its zenith with a long passage about Elvis’ 1968 Christmas special on NBC, coordinated by the singer and show’s hip director, Steve Binder (Dacre Montgomery). While Parker laments that Elvis is “throwing his career away to sing spirituals with a bunch of longhairs,” the special becomes Elvis’ reclamation of his personal brand. The performance is topped with the politicized mourning of the assassinated RFK, albeit with the word “Elvis” towering in red lights on the stage—a visual that makes the moment about Elvis, not the fallen US Senator.

In Luhrmann’s hands, Elvis isn’t so much a problematic appropriator of Black music as an agent of change, emblematizing how art pushes the acceptable limits of culture, thereby enacting social progress. Luhrmann reveals the cycle of influence by drawing connections between Elvis’ antecedents and today’s hip-hop artists on the soundtrack (Nardo Wick, Eminem, CeeLo Green, Denzel Curry, et al.). The film’s central theme remains the uneasy relationship between art and commerce in the music industry—and by extension, the film industry. For that reason, it’s easy to see why Luhrmann would be attracted to framing the story through Parker’s eyes, given that the huckster sees Elvis as a slot machine pouring musical tokens out of his mouth. Luhrmann must have recognized that his film would have a similar appeal. Devoted fans across the globe will rush out to see Elvis, regardless of the mixed critical reception, making the topic almost foolproof in box-office terms. Luhrmann is free to experiment with form and nurture bizarro performances within that money-making framework. Whether he pushes the culture forward with Elvis is up for debate.

In Luhrmann’s hands, Elvis isn’t so much a problematic appropriator of Black music as an agent of change, emblematizing how art pushes the acceptable limits of culture, thereby enacting social progress. Luhrmann reveals the cycle of influence by drawing connections between Elvis’ antecedents and today’s hip-hop artists on the soundtrack (Nardo Wick, Eminem, CeeLo Green, Denzel Curry, et al.). The film’s central theme remains the uneasy relationship between art and commerce in the music industry—and by extension, the film industry. For that reason, it’s easy to see why Luhrmann would be attracted to framing the story through Parker’s eyes, given that the huckster sees Elvis as a slot machine pouring musical tokens out of his mouth. Luhrmann must have recognized that his film would have a similar appeal. Devoted fans across the globe will rush out to see Elvis, regardless of the mixed critical reception, making the topic almost foolproof in box-office terms. Luhrmann is free to experiment with form and nurture bizarro performances within that money-making framework. Whether he pushes the culture forward with Elvis is up for debate.

If the film’s first two-thirds about Elvis becoming a superstar meander and prove visually chaotic, the tone normalizes in the last act, when Parker negotiates a deal at The International in Las Vegas. Stoking Elvis’ paranoia about security, Parker shackles the star in a contract that should have been six weeks but lasts five years—a reveal played against a stage performance of “Suspicious Minds,” with the none-too-subtle lyric “caught in a trap” echoing. While Elvis becomes a Vegas sideshow act worthy of countless impersonators, Dr. Nick’s (Tony Nixon) “vitamin” shots keep the exhausted King performing night after night, headlining a 30-piece orchestra and two sets of background singers. Although too thin for this era’s Elvis, Butler commits to the sweaty stage performances, complete with karate moves and almost evangelical quaking. But once again, Luhrmann’s focus is Parker’s concentration on business affairs to feed his appetite for money. How is Elvis caught in this trap? According to the movie, it’s not his avarice or unchecked spending but his father’s incompetence as a business manager, not to mention his hillbilly clan’s unchecked spending. Elvis presents him as a victim of Parker, barely addressing the star’s erratic behavior and overly lavish lifestyle—collecting a veritable zoo of animals, posing as a cop, gifting Nixon a gun, and so on. The fact that we rarely see beyond the foyer of Graceland reveals how hesitant Luhrmann was about exploring Elvis’ vast superficiality.

So when Parker resolves that Elvis “just needed love,” it can’t help but feel like an oversimplification. Suffice it to say, Luhrmann’s film makes the same mistake. Elvis doesn’t have the patience or nuance to negotiate the many complicated aspects of the singer’s life. Luhrmann resolves to take the easier route and tell Parker’s story. Although the film delivers a few rousing live performances thanks to Butler’s committed turn, most dramatic scenes don’t live and breathe—even as they move with all the variegated energy Luhrmann, cinematographer Mandy Walker, and the editors (Matt Villa, Jonathan Redmond) can muster. There’s not one camera movement or cut that doesn’t whoosh into the moment, outshining any hope at a meaningful connection to what otherwise should be complex characters. What disappoints the most is that Luhrmann’s wild visuals and use of Parker’s subjectivity (a colossally misguided Hanks performance) don’t distract from Elvis’ formulaic biopic structure. It’s the same old story, except bedazzled into an eyesore. Still, Butler’s undeniably charismatic screen presence and the momentum Luhrmann injects into the storytelling make Elvis something you can’t help but watch, even if it remains an unsatisfying curiosity.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review