Elizabeth

By Brian Eggert |

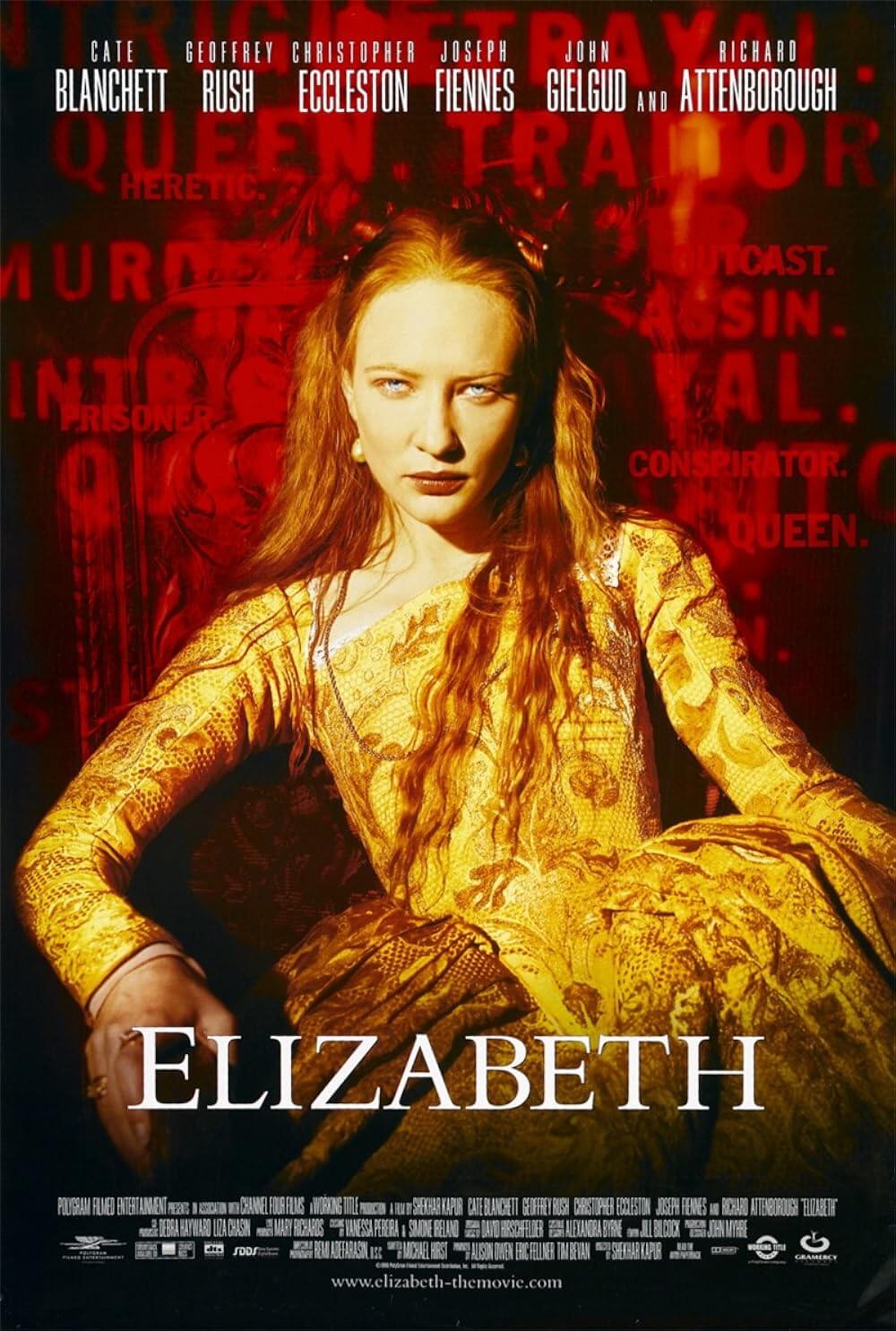

Movies sporting a single standout performance often lack in other areas; in truth, an outstanding performance can drain the remainder, lessening it. The actor mutes the narrative, embossing a script that might not deserve attention but for that one part. See Philip Seymour Hoffman in Capote or Jamie Foxx in Ray—great performances in so-so movies. And then there are movies like Elizabeth, which features high production values, fluid camerawork, and breathtaking art direction, all in addition to the tour de force performance by Cate Blanchett. I imagine it would still be great if Blanchett were not present; however, I can’t see another actress giving her part such humanity.

Appropriately dark, Elizabeth carries an ominous tone of political and religious dread through every scene. As it begins, Queen Mary I of England is dying. Being Roman Catholic, both she and her advisers worry over her sister’s potential takeover. Elizabeth, a Protestant, is accused, even jailed for supposedly conspiring to assassinate Mary, her half-sister. After a tumor-ridden uterus finally kills her, Mary’s crown falls to Elizabeth, who enters her coronation somewhat naively, not realizing how much hatred is felt for her throughout her kingdom or how much danger surrounds her.

In these first scenes, Blanchett shows a bright innocence, one completely unaware of her position’s sacrifices. It’s like watching a brave child finally becoming aware of the cruel world, and it’s heartbreaking. Her adviser Sir William Cecil (Richard Attenborough) keeps at Elizabeth about her dire situation, her throne that remains threatened pending her marriage, and her “loyal” staff that conspires against her. Grudging parties in Scotland and France threaten her crown should she not marry and form an alliance. Cecil pleads for Elizabeth to consider marriage proposals from the Spanish King and Frenchman Duc d’Anjou, an incorrigible fiend played with levity by Vincent Cassel. Meanwhile, she has her own lover, Robert Dudley, Early of Leicester (Joseph Fiennes), a man the whole kingdom seems to know shares her bed. Her true love, however, is England.

If only the Duke of Norfolk (Christopher Eccleston) realized her passion; he protests her initiation at the outset, and then, behind closed doors, he works to dethrone she who would not follow Catholicism devoutly. Norfolk is supported by The Pope (John Gielgud), who writes decrees stating that anyone following the new Queen Elizabeth follows a heretic. Religious assassin John Ballard (Daniel Craig, before he was James Bond) is sent to dispose of Elizabeth for the church; instead, he offs one of her attendants with a poisoned dress.

However, in Walsingham (Geoffrey Rush), Elizabeth does have one ally, a man who respects his Queen for her independence. With baleful eyes, he sits in the shadows, assuring her “safety” and all that that entails. When Mary de Guise (Fanny Ardant) threatens England, Walsingham returns her threats with metaphors about how England must lie in bed with either Spain or England. Rush says this raising an eyebrow. The next day, in her bedchamber, De Guise’s nephew Duc d’Anjou finds his aunt murdered. Rush is an enthralling onscreen presence; his Walsingham believes in Elizabeth’s ability to control her council, as they underestimate the fairer sex. While she outwits them, he takes action to assure her wit is enough. Rush offers pitch-perfect charm in his malicious plotting, always with a menacing smile, standing in the background, doing the most vicious acts to support his Queen.

Relatively unknown in 1998 when this picture was made, Blanchett’s appearances in Oscar and Lucinda and The Wedding Party didn’t hint at what she brings to the screen here. She achieves a range of personality traits: the timid and emotionally free young woman; the sexless and powerful leader; the panicky, emotional paranoiac (a personality that recalls Bette Davis’ own Elizabeth interpretation from The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex). Blanchett has gone on to challenge the best living actresses, shaking Meryl Streep and Judi Dench down from their platforms with her roles in The Aviator, Notes on a Scandal, and this. I truly believe Blanchett when her Elizabeth claims, “If I choose, I have the heart of a man”—a statement we’ll see fulfilled in total later this year when she plays folk poet Bob Dylan in I’m Not There.

Director Shekhar Kapur (The Bandit Queen) revels in strong female characters. Elizabeth, his first American feature, is no exception. His film is beautifully realized with equal amounts of Hollywood glamour and the dusty reality of sixteenth-century architecture. Kapur makes wonderful use of Blanchett’s abilities, utilizing her bodily and facial control to achieve this film’s last startling moments when she becomes The Virgin Queen—a pure symbol, rather than a person filled with subjectivity.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review