Elena

By David Hill |

When watching Elena in 2020, one cannot help but notice certain parallels to this year’s Academy Award winner Parasite, despite the significant stylistic and tonal differences between the two films. Not only are both the work of a master director in full command of his craft, but they both deal with the economic divide between the haves and the have-nots, and a large portion of them takes place in two opposing locations: An expansive and luxurious home where the rich live, and a cramped and scrappy apartment where the poor live. In the case of Elena, the luxurious home is situated in a modern and prestigious district in the center of Moscow, and it belongs to retired patriarch Vladimir (Andrey Smirnov, who is not only an actor, but also a respected film director). The scrappy apartment is situated in a Soviet apartment block in the run-down outskirts of Moscow, and it is inhabited by the unemployed Sergey (Aleksey Rozin) and his family. The titular Elena (Nadezhda Markina), an ordinary woman in her fifties who used to be a nurse, is a connective link between the two classes—Vladimir is her husband with whom she lives, and Sergey is her son from a previous marriage.

To use the phrasing in Parasite, Sergey hopes to use his mother’s marriage to Vladimir to “cross the line.” Much to the latter’s dismay, he makes Elena ask her husband for money so that Sergey’s teenage son can go to college and thereby avoid military service (the film never explicitly explains how Vladimir’s money would allow Sergey’s teenage son to go to college, but it’s safe to assume that Sergey’s plan involves bribery). Vladimir refuses to help, stating that there is no reason for him to pay for the education of somebody who is effectively a stranger to him, and that Sergey should take care of his own son. Moreover, after having had a near-fatal heart attack, Vladimir declares to Elena that he plans on writing a will with the following content: Katya (Elena Lyadova, who provided the voice for Marie Bonnevie’s character in The Banishment), his spoiled daughter from a previous marriage, will inherit almost everything, and Elena will have to make do with an annuity. This puts Elena in a moral dilemma, and she decides to take matters into her own hands through drastic action.

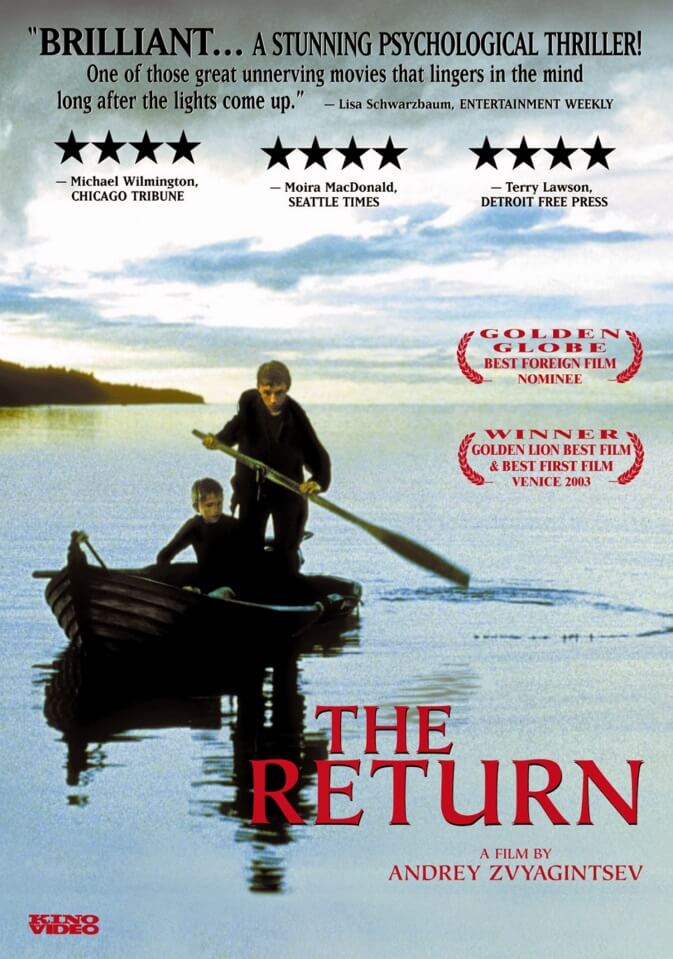

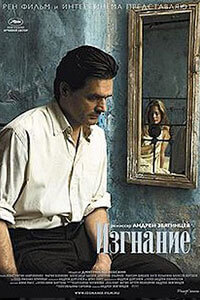

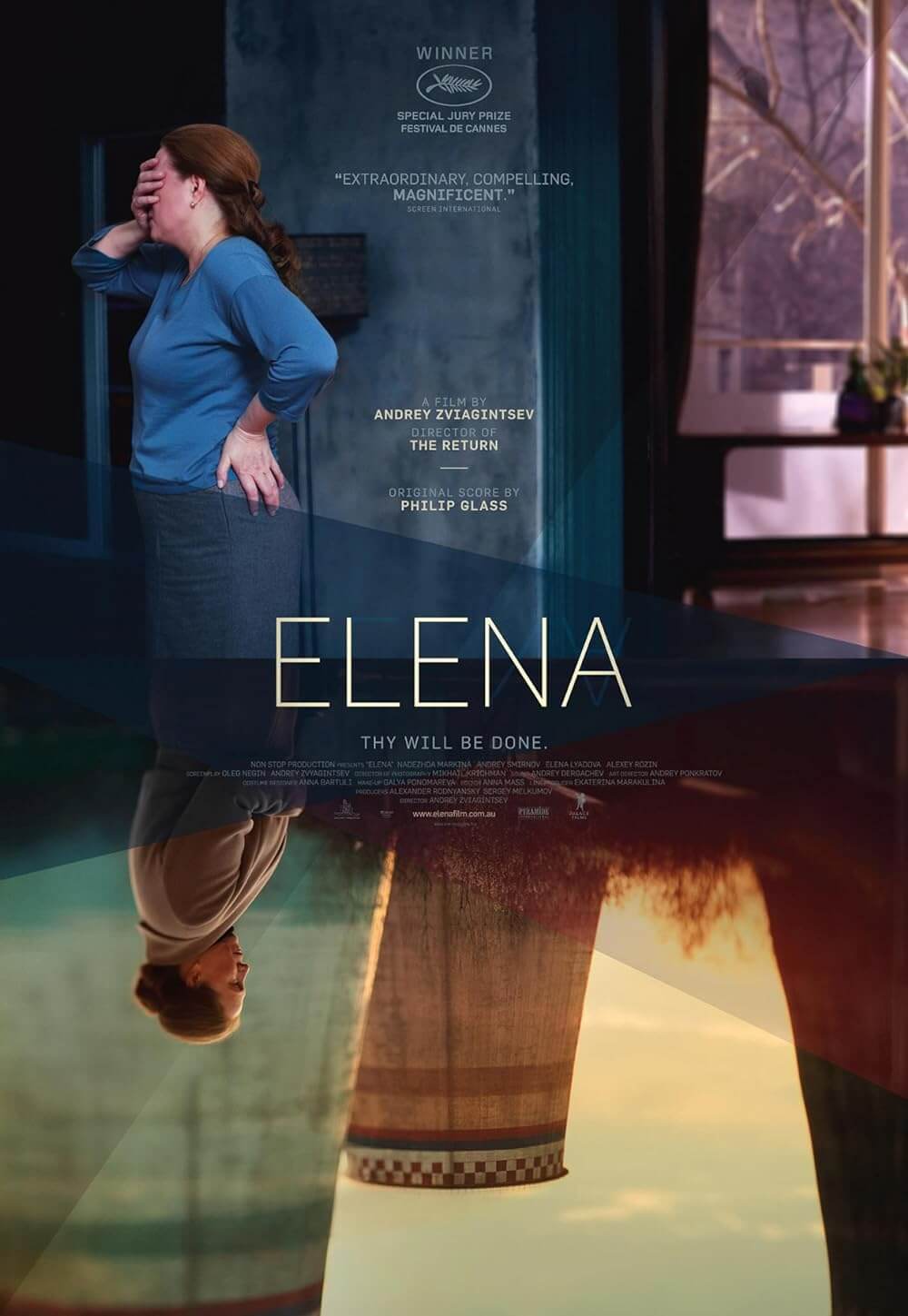

Elena is Russian director Andrey Zvyagintsev’s third feature film. It premiered in the Un Certain Regard section at the Cannes Film Festival in 2011, where it won the Special Jury Prize. The film was a step in a new direction for Zvyagintsev after his sophomore feature The Banishment had been rather similar to his Golden Lion-winning debut The Return. In particular, Elena feels more grounded and specific than the director’s two previous films, which had an abstract feel to them and mainly worked on a metaphorical level. At first glance, viewers might therefore get the impression that Elena is perhaps a minor entry in Zvyagintsev’s filmography, but that would be a serious misconception. The film’s comparatively grounded and specific nature makes for a more compelling and emotionally engaging viewing experience, although Zvyagintsev still keeps viewers at a certain remove. Furthermore, even though Elena lacks the epic and almost mythical dimension of The Return and The Banishment, it still has much to offer beyond its surface.

Zvyagintsev’s third film deals with several themes, and it lends itself to various readings. As indicated above, it can be read as a meditation on class conflict; specifically, the economic divide between the haves and the have-nots. The film mainly explores this theme through the above-mentioned juxtaposition of the rich Vladimir and the poor Sergey, as well as their respective homes that could not be more different from each other. Both Vladimir’s apartment and Sergey’s flat were sound stages that were built for the film (the houses that can be seen next to Vladimir’s apartment were simply panels covered with photos of a typical Moscow courtyard, which is something that viewers will only notice when they are aware of it). Sergey’s flat is a replica of real flats from Soviet apartment blocks built in the ’70s and ’80s, which Zvyagintsev described as “rabbit hutches” in an interview. To underline the claustrophobic nature of the flat, nearly all scenes that take place therein were shot from the same angle, whereas Vladimir’s expansive apartment was covered from several different angles.

Zvyagintsev’s third film deals with several themes, and it lends itself to various readings. As indicated above, it can be read as a meditation on class conflict; specifically, the economic divide between the haves and the have-nots. The film mainly explores this theme through the above-mentioned juxtaposition of the rich Vladimir and the poor Sergey, as well as their respective homes that could not be more different from each other. Both Vladimir’s apartment and Sergey’s flat were sound stages that were built for the film (the houses that can be seen next to Vladimir’s apartment were simply panels covered with photos of a typical Moscow courtyard, which is something that viewers will only notice when they are aware of it). Sergey’s flat is a replica of real flats from Soviet apartment blocks built in the ’70s and ’80s, which Zvyagintsev described as “rabbit hutches” in an interview. To underline the claustrophobic nature of the flat, nearly all scenes that take place therein were shot from the same angle, whereas Vladimir’s expansive apartment was covered from several different angles.

Another major theme of Elena is the importance and corruptive power of money in contemporary society. It is notable that most exchanges between the film’s characters (even those between husband and wife, and between parent and child) feel like cold transactional exchanges that are void of kindness and warmth, and instead dominated by greed and mistrust. In addition to these exchanges and the above-mentioned juxtaposition of Vladimir and Sergey, Elena contains some more subtle references to the economic divide and the importance of money in today’s world. Not only is there a striking shot of Vladimir, shielded in his luxury car, driving by a group of mostly immigrant construction workers, but there is also much materialism on display throughout the film (such as the TVs that often run in the background and mostly show pointless ads or talk shows, or a woman on a train who tries to sell cheap magazines to the train’s passengers).

Moreover, Elena examines the importance of family ties and the responsibilities resulting from them, as well as the gap between generations. Before we meet any characters from a younger generation than Elena’s, there is an early scene in the film that highlights this theme: Elena leaves her house and walks down one side of the street with old-fashioned clothes and her head covered by a headscarf; she is juxtaposed with another, much younger woman who walks down the other side of the street in a modern outfit and her hair waving around. Another important theme of the film lies in gender roles: Zvyagintsev shows contemporary Russia as a patriarchal society where men, regardless of their social standing (Sergey’s behavior towards women is no less condescending than Vladimir’s), dominate, while the role of women is limited to serving men. Zvyagintsev highlights this and the hard work carried out by women by lingering not only on Elena’s housework, but also on a nurse making a bed in a hospital and an attorney’s assistant preparing drinks for the participants of a meeting. Furthermore, it is notable that it is a woman who saves Vladimir when he has a heart attack while swimming. However, despite the themes of Elena being more political than the ones that Zvyagintsev explored in his previous work, the film never turns didactic or overtly political due to the director’s usual observational and non-judgmental approach.

Another difference between Elena and Zvyagintsev’s previous films is that the former was mostly shot in interiors and on sound stages (which the director described as “an interesting artistic constraint”), whereas both The Return and The Banishment contained several exterior sequences that were shot on location. Furthermore, Elena features fewer religious references than the director’s previous work, although religion still plays a role. There is a scene in a church that was written by Zvyagintsev, who received his first co-screenwriting credit for the film. According to Zvyagintsev, his co-writer Oleg Negin initially wanted to leave that scene out, but the director insisted that it was necessary, which once again underlines his affinity to religious themes. In addition to that, Elena is Zvyagintsev’s first film whose main character is a woman. Both The Return and The Banishment had focused on male characters, and the female characters of those films had only played limited roles.

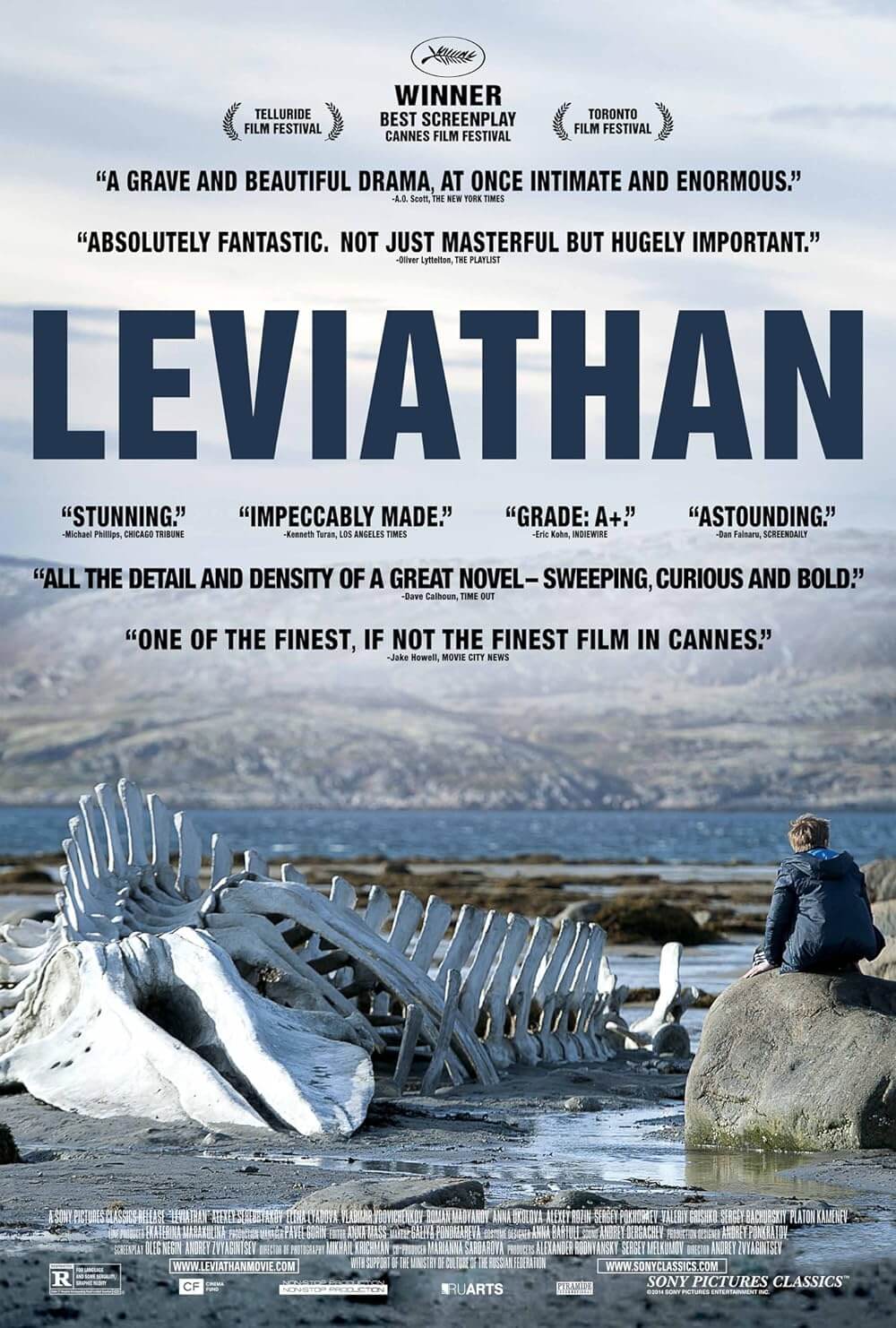

The use of Philip Glass’ “Symphony No. 3” as the film’s score adds yet another dimension to Elena. Even though the score is used sparingly, it is much more imposing than the rather restrained scores of Zvyagintsev’s previous features, and it adds much to the film’s tense and compelling atmosphere. However, the score was not composed specifically for the film. Glass, described as “the greatest composer of our time” by Zvyagintsev, had already written his “Symphony No. 3” back in 1995. When Zvyagintsev asked Glass for permission to use his music in Elena, the latter offered to write something new, but Zvyagintsev declined the offer as he felt that “Symphony No. 3” would fit the film perfectly. Zvyagintsev and Glass did however agree on working together on the director’s next film Leviathan, but that ultimately did not happen due to scheduling conflicts. Therefore, Zvyagintsev once again ended up using music that Glass had already written at an earlier time.

Despite the above-mentioned differences to the director’s previous work, Elena is still unmistakably a Zvyagintsev film. It contains trademarks that were already established in The Return and The Banishment: Masterful direction with a great sense of framing, skillful and controlled cinematography (once again by Zvyagintsev regular Mikhail Krichman), a muted color palette, several long takes, great acting (in particular, Nadezhda Markina’s performance as the titular Elena is outstanding), a deliberate pace, long sequences without dialogue, an open ending, a tense and gloomy atmosphere, and animal symbolism (including a dead horse and birds that can be seen and heard throughout the film). One of the things that stand out among the technical aspects of Elena is the restraint that Zvyagintsev uses throughout most of the film. Nearly all shots are precisely composed and filmed by a fixed camera–with the exception of a wholly unexpected scene towards the end that was shot with a handheld camera, which is all the more effective for its formal contrast to the rest of the film.

While Elena did not quite receive the same attention and acclaim as Zvyagintsev’s Golden Lion-winning debut The Return, it deservedly earned rave reviews from critics around the globe (with several critics at Cannes lamenting the fact that the film premiered in the Un Certain Regard section instead of competing for the Palme d’Or against the likes of Terence Malick’s The Tree of Life and Lars von Trier’s Melancholia). The film was indeed a return to form for the director after his divisive and overly abstract sophomore feature The Banishment, and it constituted a step in a new direction for him. Compared to Zvyagintsev’s previous work, the film feels more grounded and specific, which makes for a more compelling and emotionally engaging viewing experience. However, the director was still able to maintain many trademarks that made his first two films stand out. In particular, Elena is once again challenging and patience-requiring, but ultimately, it’s a deeply rewarding film that is impeccably made.

Bibliography:

Dale, Austin. “Andrei Zvyagintsev Talks ‘Elena,’ His Rebirth and Philip Glass.” IndieWire. 17 May 2012. https://www.indiewire.com/2012/05/andrei-zvyagintsev-talks-elena-his-rebirth-and-philip-glass-47346/. Accessed 12 October 2020.

Graffy, Julian. “Andrei Zviagintsev: Elena.” KinoKultura. January 2012. http://www.kinokultura.com/2012/35r-elena.shtml. Accessed 12 October 2020.

Menashe, Louis. “Elena.” Cinéaste. Vol. 41, No. 1, Winter 2015, pp. 64-65.

“About Elena.” Interview with Andrei Zvyagintsev. Pyramide Video, DVD, March 2012.

David Hill is a lawyer from Switzerland who currently works as a legal counsel for an insurance company. He has long had a passion for cinema, and he uses most of his spare time to watch and research films. His main interest focuses on arthouse films, and he occasionally makes contributions to Deep Focus Review as a guest writer.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review