Elemental

By Brian Eggert |

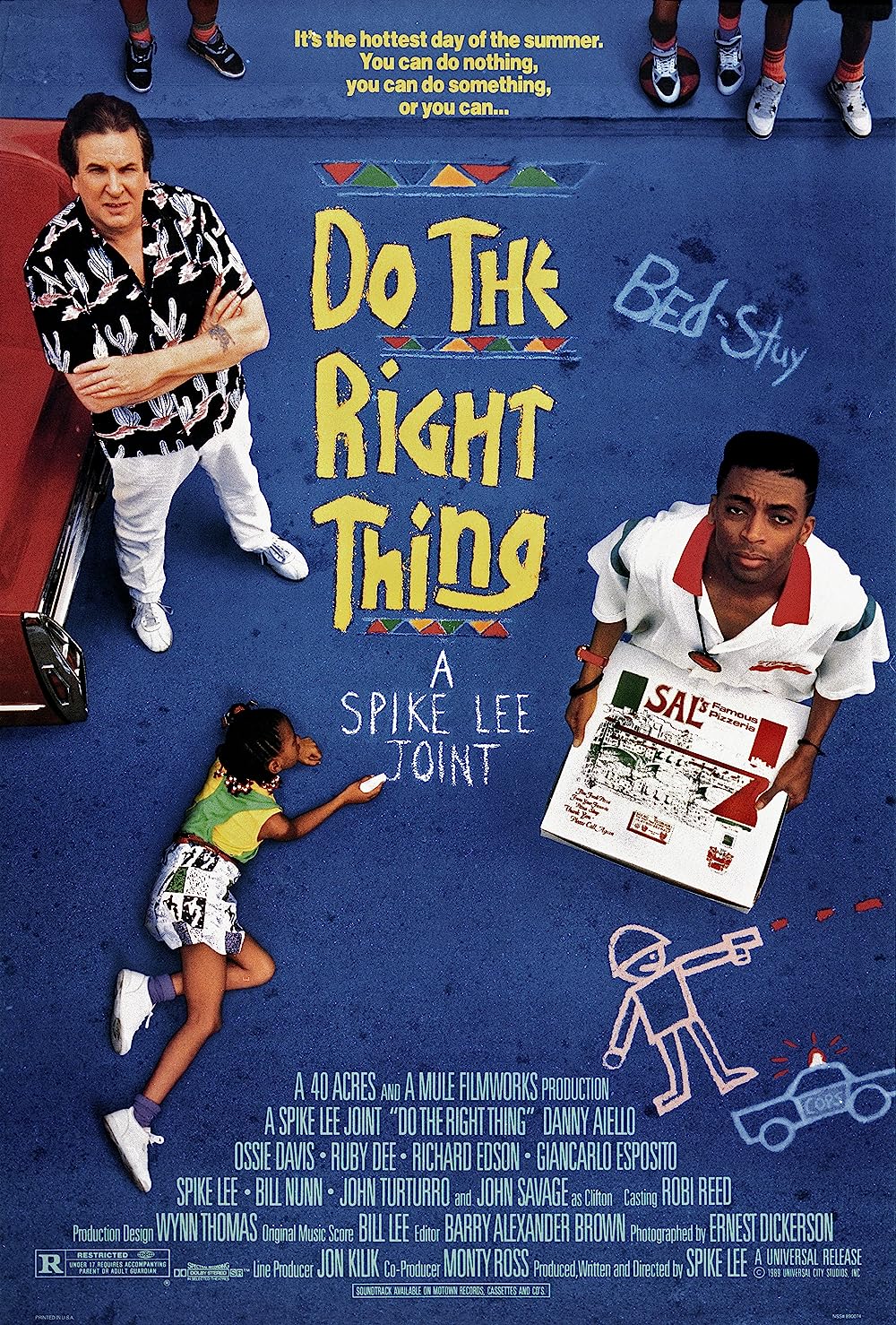

Elemental looks like standard Pixar fare, complete with personified ideas serving as characters. Sure enough, the story concerns a world inhabited by the four classical essential elements (water, fire, air, earth). Given how these abstract concepts take on human characteristics, the setup invites easy, surface-level comparisons to Inside Out (2015) or any of the studio’s other features. Even the animation looks average—the studio’s most cartoony yet—with some obvious and even banal world-building details, corny dialogue, and character designs built around the elements. But the themes and protagonists add to a tender, warm-hearted story of star-crossed lovers that feels vital for today. Not only does it supply a compelling analogy for racial prejudice—the story beats recall everything from Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967) to Do the Right Thing (1989)—but it’s also a genuinely romantic movie. Early in Elemental, just when you start to think Pixar has lost its touch, the studio blindsides you with another moving and inventive work of animation and storytelling.

Initially, the screenplay (credited to John Hoberg, Kat Likkel, and Brenda Hsueh) could be mistaken for a Pixar parody. The story takes place in Element City, a vast metropolis whose inhabitants have arrived in waves of immigrants. The last group of immigrants to arrive are the not so cleverly named Fire People, who hail from Fire Land—generic labels that could have been replaced with more creative fire-related alternatives. Other element groups worry that the Fire People will destroy everything and bring harm if touched, prompting one character to declare, “Elements don’t mix.” Our protagonist is named Ember Lumen, of course, and voiced by Leah Lewis. She’s bound by the traditions of her parents, Bernie (Ronnie del Carmen) and Cinder (Shila Ommi). With their devotion to traditionalism kept in an eternal blue flame that originated in the old country, Ember’s father operates a small store that sells Fire People food and wares, while her mother gives smoke readings in the back room. Ember’s parents have raised her with the expectation that someday she will take over the family store, but she has a fiery temper, leaving Bernie with doubts.

Facing pressure to uphold the family legacy, Ember becomes angry, and her explosive temper inadvertently causes the family store’s water pipes to burst. This prompts the arrival of a city inspector, a Water Person named Wade Ripple (Mamoudou Athie). While Ember tries to stop him from reporting the leaky family store to the city, she also has her first meaningful interaction with someone of his persuasion. Wade, a nice guy who’s easily reduced to blubbery tears, agrees to help her, introducing Ember to the multicultural world of Element City outside of her ethnically isolated neighborhood. They fall for each other, prompting a dating montage and Ember’s awkward visit to a Ripple family dinner. The restrained romance is backed by a sense of danger, suggesting that if Ember touches Wade, he’ll boil and evaporate, or alternatively, his water will put out her flame. To be sure, that’s not the only allusion to romantic chemistry. References to “pruning” among Earth People, the chemical reaction when Ember and Wade finally touch, and the “hanky panky” between Ember’s parents make Elemental a rather horny (albeit PG-rated) love story.

Still, I struggled with the computer animation in Elemental. It contains an array of incongruous styles that don’t always feel part of a whole. Fire People resemble the flat-looking fire character Calcifer from Howl’s Moving Castle (2004), represented with bold lines around facial features and an ever-burning body shape—thus continuing the tradition of Pixar borrowing from Hayao Miyazaki. Wade and his fellow Water People have more substance; light travels through their semi-transparent bodies, creating a three-dimensional depth. The Cloud People, too, seem tangible, like floating cotton candy. The least inspired designs belong to the Earth People, who play the smallest role in the story. They recall the rock trolls from Frozen (2013), looking like stone-nosed garden decorations. Meanwhile, non-personified water and some objects often look photoreal, contrasting the cartoonish character designs. Certainly, the characters can sometimes feel like they were assembled for different movies, each with a distinct style. But the disparate appearances also embody the multicultural concept behind Element City, so what might feel inharmonious at first ultimately bolsters the themes, even if it never quite achieves visual harmony.

Indeed, if the animation seems more functional than eye-popping, Elemental’s message resonates as a parable for the dangers of intolerance (it will probably be banned in Florida schools). Disney’s Zootopia (2016) covered similar ground but didn’t reach beyond its basic ideas about discrimination. Although in Elemental the groups use predictable epithets such as “fireball” and “cloud puff,” it also considers the economic conditions of race by portraying more established elements who take their privilege for granted. Wade, whose family lives in a posh apartment complex with residential security guarding the front door, doesn’t understand why Ember feels beholden to tradition, denying herself the chance at a career in glass sculpture to instead work at her family’s store. “Getting to do what you want is a luxury,” she informs Wade, which brings to light how first-generation immigrants often lack the advantages of established generations. Not only does the film confront such privilege, but the story delivers a thoughtful message about the importance of empathizing with people whose social backgrounds may be different from yours, as well as respecting traditions but not mindlessly conforming to them.

Director Peter Sohn, who helmed 2015’s underrated The Good Dinosaur, turns what might have been a by-the-numbers movie into a surprisingly heartfelt and insightful story—in other words, a Pixar film. While it supplies a worthwhile lesson with unmistakable parallels to contemporary issues of race and culture, it also earns a tear or two from the endearing romance. And despite the sometimes obvious world-building, the material works, even when it’s not altogether narratively satisfying. Take a subplot about cracked dam doors, which allow water through that could destroy the Cinders’ home. Even though the problem is never adequately resolved, when the dam bursts due to the city’s negligence, it cannot help but recall the levees bursting in New Orleans, flooding neighborhoods that have been deprioritized due to a prejudicial authority. Armed with bright, if unsubtle commentaries about racism, traditionalism versus progressivism, and the dynamism of urban communities, Elemental, like Pixar’s Onward (2020) and Luca (2021), feels like a low-tier effort. But it’s a fully realized form-follows-function concept that, like the company’s best work, goes deeper than its surface implies.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review