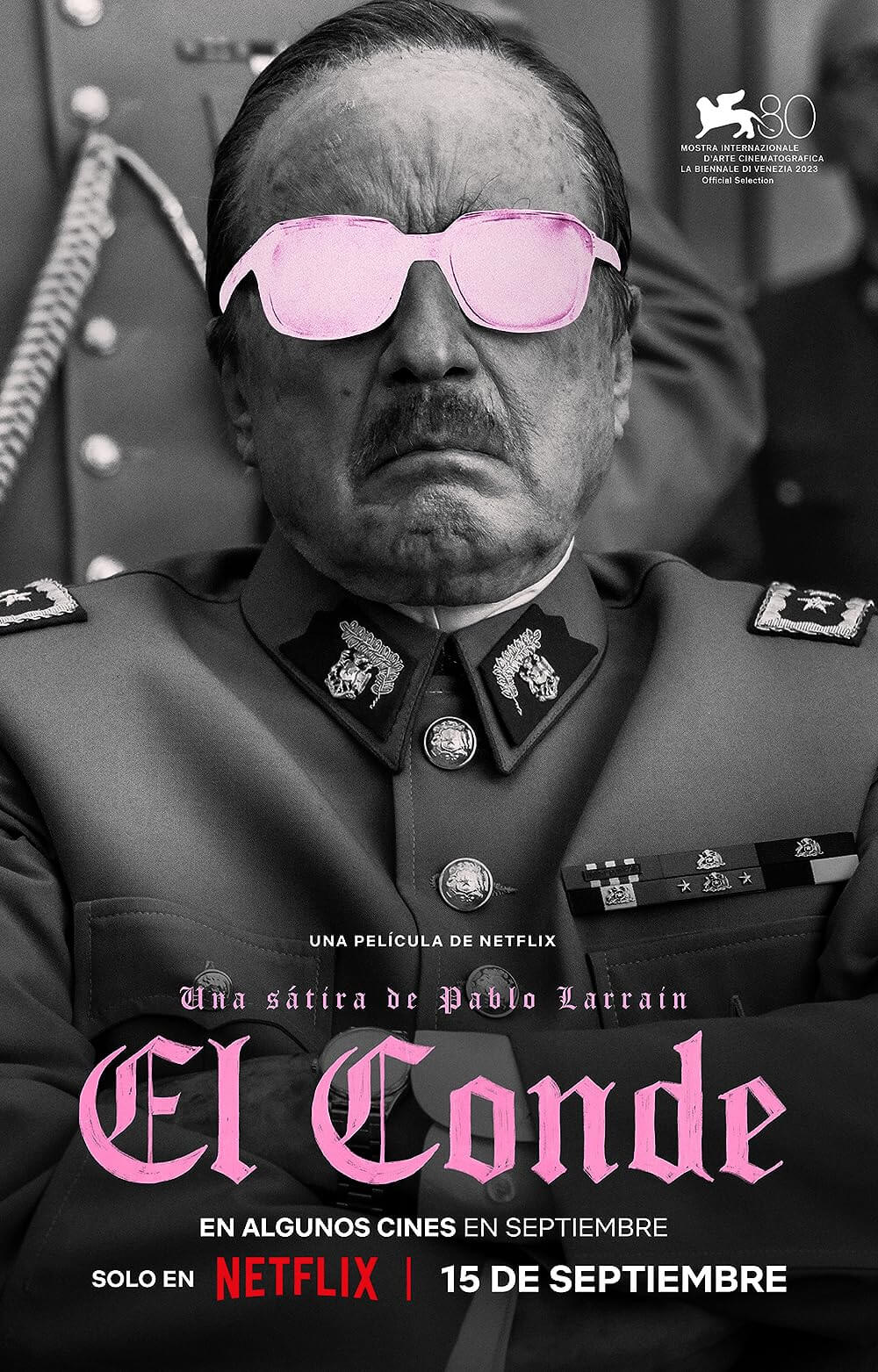

El Conde

By Brian Eggert |

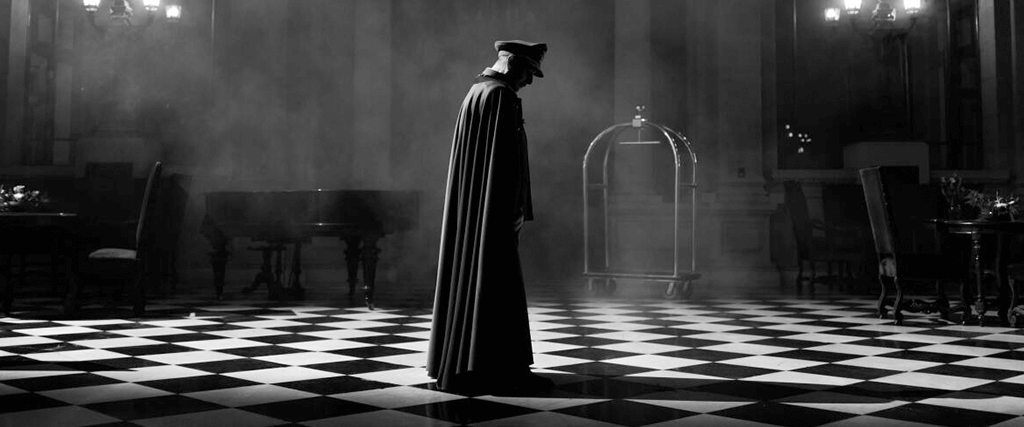

Pablo Larraín’s El Conde (The Count) imagines the brutal Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet as a vampire in an extended metaphor about political despots. Not long after Pinochet’s reported death at 91, the fascist leaps into the sky, garbed in a billowing cape and general’s uniform, looking like an aged military commander crossed with Superman and Dracula. He glides over vast monochrome landscapes and bodies of water before arriving in Santiago, where he hunts for sustenance. Finding a woman in bed, he penetrates her neck with a knife and carves a black opening into her chest cavity. He extracts her still-beating heart, drops the organ into his victim’s blender, and guzzles down the thick, sanguine purée like a revitalizing smoothie. Between the monster feeding on his country’s people, living forever, and reappearing under similarly corrupt identities, Larraín uses potent imagery to remark on how tyrants will continue to have power throughout history unless they are exposed and held accountable for their crimes, allowing their respective countries closure and alerting them about similar figures in the future. While the film’s message is rarely more complicated than its premise, Larraín’s execution is a sublime blend of gorgeous filmmaking and black-as-pitch humor.

El Conde begins with an alternate origin story for Pinochet (Jaime Vadell), whose 1973 military coup took down President Salvador Allende’s leftist Popular Unity government, submerging Chile into 17 years of violent and oppressive rule under the general-turned-dictator. Inspired by pictures of Pinochet wearing a cape, Larraín’s screenplay, co-written with Guillermo Calderón, makes no mistake about its broad caricature—the film is a political cartoon in cinematic terms. As the British-voiced and wholly unreliable narrator (Stella Gonet) explains, Pinochet’s fictional origins start in France some 250 years ago. There, he served as an officer in the army of Louis XVI—where he first realized he was a vampire and fed on sex workers—before switching sides during the French Revolution. After France’s aristocracy fell, the devout monarchist fought against similar revolutions in Haiti, Russia, and Algeria. Eventually, he found his way to Chile, where he found a bride, Lucía (Gloria Münchmeyer), often rumored to be the controlling voice in his ear, compelling him to commit his worst crimes against humanity. He stops a Bolshevik incursion, rises to power, and quickly becomes a millionaire by feeding on the Chilean people, hiding his money in secret bank accounts, most of them in the USA.

Born during the Pinochet regime, which lasted until 1990, Larraín has explored this era before in his earlier works: Tony Manero (2008) echoed the unscrupulous and decadent times by following a Chilean man whose only dream is to become like John Travolta’s character in Saturday Night Fever (1977) by any means necessary. Post Mortem (2010) follows a pathologist’s assistant who is expected to cover up the true causes of the deaths during Pinochet’s coup. And among Larraín’s best films to date, No (2012) centers on how politicians used advertising techniques for a winning campaign to vote Pinochet out of office. Although the director is perhaps best known today for his immersive takes on famous female icons in Jackie (2016) and Spencer (2021), his latest and tenth film shows him experimenting with genre and Chilean history in a manner unlike anything he’s done before. Using horror for political satire in playful ways, he delivers an extension of the magical realism often attributed to South American fiction, albeit with cinematic antecedents in the classical horror genre.

El Conde isn’t intended to be scary or particularly thrilling in the mode of typical vampire fare; its deployment of gothic horror visual motifs and bloodsucker iconography serve the satire first. Take how, despite Pinochet’s record of political murders and torture, he does not mind being called a killer since, in his mind, his acts supported his country; however, he takes issue with being called a thief, which he openly acknowledges as accurate. But in his twisted logic, that crime is selfish rather than for the country. Inhabiting a decrepit mansion in the south, Pinochet lives with Lucía and his longtime Russian lieutenant-turned-butler, Fyodor (Alfredo Castro). Caught in a depression since his false death, he intends to stop drinking blood and say goodbye to the cruel world. Meanwhile, the narrator supplies outright commentary by passing judgment on these subordinates, describing Lucía as having done nothing but “open her legs and allow a soldier to fornicate with her.” Larraín’s best joke resides in his reveal of the narrator’s identity, which won’t be spoiled here, but which further remarks on the circularity of authoritarianism among political leaders.

El Conde isn’t intended to be scary or particularly thrilling in the mode of typical vampire fare; its deployment of gothic horror visual motifs and bloodsucker iconography serve the satire first. Take how, despite Pinochet’s record of political murders and torture, he does not mind being called a killer since, in his mind, his acts supported his country; however, he takes issue with being called a thief, which he openly acknowledges as accurate. But in his twisted logic, that crime is selfish rather than for the country. Inhabiting a decrepit mansion in the south, Pinochet lives with Lucía and his longtime Russian lieutenant-turned-butler, Fyodor (Alfredo Castro). Caught in a depression since his false death, he intends to stop drinking blood and say goodbye to the cruel world. Meanwhile, the narrator supplies outright commentary by passing judgment on these subordinates, describing Lucía as having done nothing but “open her legs and allow a soldier to fornicate with her.” Larraín’s best joke resides in his reveal of the narrator’s identity, which won’t be spoiled here, but which further remarks on the circularity of authoritarianism among political leaders.

Enter Pinochet’s five grown children, who have been stripped of their power and privilege since their father’s public death. Knowing he’s a vampire and has untold bank accounts where he hid the fortune he siphoned from Chile, the children hire a mathematically inclined nun, Carmen (Paula Luchsinger), who agrees to discreetly investigate Pinochet’s papers and provide an accounting of his funds—not to mention his crimes—while promising to save whatever of his soul remains. “She wants to cast the devil out of me,” Pinochet observes. “But I’ve got nothing left inside.” Larraín also uses Carmen as a critical commentator when she interviews the children, exposing their banal evil as they make excuses for their father, noting that other dictators did worse. Carmen even breaks her pretense in reality-defying scenes where she openly insults the children or admits her plan to sow confusion and infighting among them. Though, her confessions go unnoticed, and her mission is far from pure. Indeed, Larraín is no stranger to critiques of the Church, as seen in The Club (2015), a portrait of disgraced priests living together in exile. So despite Carmen’s holy intent to kill, expose, or save Pinochet, the Church proves corruptible—no less bent on preserving itself by stealing from the people and manipulating world leaders.

Thanks mainly to cinematographer Ed Lachman’s stunning camerawork, using an ARRI Alexa Monochrome camera designed for this production, El Conde is Larraín’s most beautiful film to date. The filmmaking draws from silent cinema, specifically Carl Theodor Dreyer’s work, referenced visually. More than once, Carmen’s appearance captures the ecclesiastical anguish seen in Renée Jeanne Falconetti’s eyes in The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928). And in a nod to Vampyr (1932), Lachman’s rich and textured imagery often deploys stark silhouettes and shadows that almost serve as irises, framing the grim central vampire against Juan Pablo Ávalo and Marisol García’s score of classical string compositions. In more modern sequences recalling that of a lonely superhero soaring above his territory, Pinochet’s scopic flights above Chile have a hypnotic, searching quality that frames the predator’s solitude in a country that despises him. Why reap the benefits of immortality in such a world? It’s almost enough to inspire sympathy for the devil, except that Larraín uses these visuals in acidic, ironic terms. (What a shame the film won’t be shown in general or even arthouse theaters and instead debuts on Netflix, robbing moviegoers from seeing this projected on the big screen.)

Vadell’s alternately sad and monstrous performance as Pinochet, who searches for reasons to keep living, may seem to deliver a toothless argument for some. The treatment threatens to portray him less as an active predator than a passive monster, languishing in the aftermath of his worst crimes, which the film does not address beyond unspecific references. However, Pinochet’s crimes are not the subject of this film. For Larraín, the character’s vampirism makes him a figurehead for the eternal evils of political leaders who operate with impunity and make excuses for their crimes, only to see their behaviors return in another form. Although El Conde may seem deeply unsatisfying in conventional narrative terms, its message is unmistakably powerful, but not in the way one might expect from a film portraying a dictator as a movie monster. Larraín is more interested in diagnosing the circulations in history and using comic hyperbole and bloody horror to do so. If the film’s entrenched yet unmissable symbolism weren’t enough, it’s also a beautiful, imaginative, and superbly crafted film, one that tests the usual function of storytelling in Hollywood cinema and offers a distinct, editorial alternative.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review