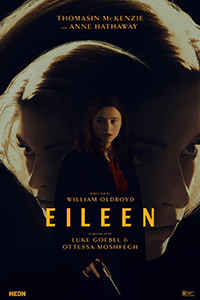

Eileen

By Brian Eggert |

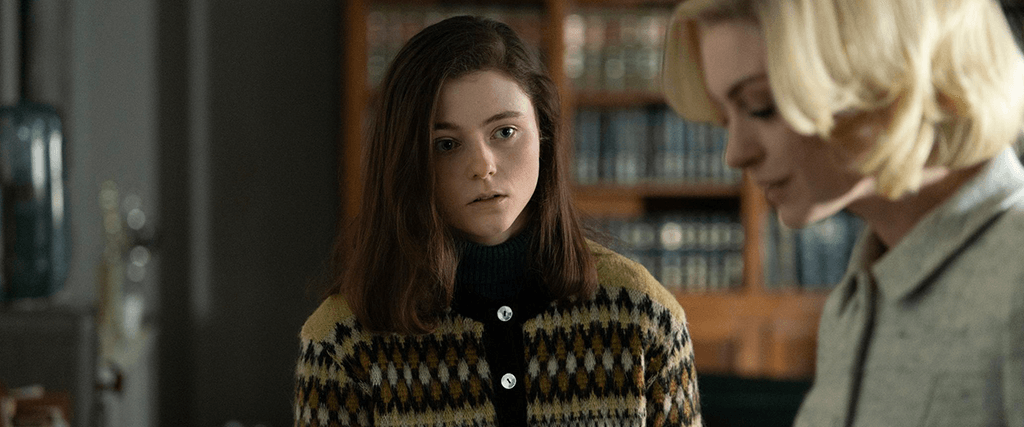

Eileen is a bit strange. Played by Thomasin McKenzie, she’s a quiet 24-year-old who works at a prison, secretly masturbates in public and on the job, and just assumes everyone wants to kill their father. At least in her father’s case, it’s not an unreasonable fantasy. A widower and former police chief played with committed, drunken abandon by Shea Whigham, her father has retired into a-bottle-a-day alcoholism and has been known to wave his gun around, aiming at passing children. He’s also deeply cruel to Eileen, remarking that while other people make moves, she’s “just there.” Her father is a product of the Massachusetts-brand hostility and misogyny that surround her, facilitating a bleak fantasy life where she alternately dreams of suicide and murder. Eileen is the subject of director William Oldroyd’s second feature, Eileen, after his superb 2016 debut Lady Macbeth, another film about a young woman suffocating in an oppressive patriarchal world, prompting a sharp response toward self-actualization. But unlike Florence Pugh’s character in the director’s debut, Eileen is far less intentional, far more complex, and far messier.

Oldroyd’s take on Ottessa Moshfegh’s 2015 novel registers somewhere between a character study and a thriller, though it’s not entirely successful in either mode. From the vintage opening titles to the moody throwback score by Richard Reed Parry (from Arcade Fire), Eileen has the feel and not altogether satisfying quality of Alfred Hitchcock’s last few films. Although it’s not closely related in terms of story or character, Eileen made me think of Marnie (1964), one of Hitchcock’s most divisive works. Both examine a disturbed young woman desperate to escape her early life, both fail to get inside their troubled protagonist’s mind adequately, and both have thriller elements without being conventionally thrilling. Moshfegh and her author-husband Luke Goebel’s screenplay leaves much about Eileen ambiguous, resolving to show, not tell—an admirable and cinematic quality, to be sure. And while equivocacy usually sparks interest and imagination, the film’s vagueness in the finale results in a disappointing anticlimax.

A bright spot in Eileen’s bleak world is the new prison psychologist, Rebecca (Anne Hathaway, in the rare performance where she disappears into her role), who pairs her Hitchcock-blonde looks—complete with peroxide hair and a classy wardrobe—with a Harvard education. To Eileen, Rebecca is everything her shitty hometown lacks, and so she mingles her desire to be Rebecca with her sexual attraction. Fortunately, Rebecca is just as bored in this setting as Eileen, so the two form a bond. Eileen interprets their drinks after work, confidant conversation, and the occasional touch as flirtations. And perhaps they are. Moreover, Rebecca takes a professional interest in the case of a local boy, Lee Polk (Sam Nivola), who brutally killed his cop father and shows no remorse. Eileen also shares an interest in Lee, watching his solitary time in the prison yard from a window. But her interest borders on envy for Lee’s willingness to act. When a prison guard (Owen Teague) whom she fantasizes about condemns that Lee killed a cop, Eileen defends him: “He killed his father—there’s a difference,” as if to say, Killing your father isn’t so bad. Remarks such as this hint at how troubled she is, and how much time she spends alone inside her private headspace.

Eileen is a textured visual experience thanks to Australian cinematographer Ari Wegner, whose impressive credits range from the based-on-a-Twitter-thread mayhem of Zola (2021) to the evocative landscapes of Jane Campion’s The Power of the Dog (2021). In each example, Wegner’s approach serves the story yet proves stylish and distinct. Here, her images recall the slight desaturation of Todd Haynes’ Carol (2015), with yellowish and pale hues to reflect the period and blue-collar environs worn by time and cigarette smoke. Costume designer Olga Mill dons the characters in unglamorous and plain clothing that disappears into the surroundings, until Rebecca arrives and shows a touch of class, channeling Kim Novak in Vertigo (1958). However, even when Eileen dresses up in her mother’s clothes to meet Rebecca during their off-hours, there’s a second-hand quality to her style that suggests she has not found herself—she’s dressing up as someone else.

Eileen is a textured visual experience thanks to Australian cinematographer Ari Wegner, whose impressive credits range from the based-on-a-Twitter-thread mayhem of Zola (2021) to the evocative landscapes of Jane Campion’s The Power of the Dog (2021). In each example, Wegner’s approach serves the story yet proves stylish and distinct. Here, her images recall the slight desaturation of Todd Haynes’ Carol (2015), with yellowish and pale hues to reflect the period and blue-collar environs worn by time and cigarette smoke. Costume designer Olga Mill dons the characters in unglamorous and plain clothing that disappears into the surroundings, until Rebecca arrives and shows a touch of class, channeling Kim Novak in Vertigo (1958). However, even when Eileen dresses up in her mother’s clothes to meet Rebecca during their off-hours, there’s a second-hand quality to her style that suggests she has not found herself—she’s dressing up as someone else.

Eileen has much in common with Carol, given the mid-century setting and age difference between the two main characters, along with styles that seem a decade older than the story—appropriately so, since Haynes’ film took place in the early 1950s. Except, Eileen doesn’t have a May-December romance with Rebecca; their friendship is less defined by attraction than by Eileen’s obsession and lingering gaze. Regardless, whatever’s developing between Eileen and Rebecca shifts sharply in the haphazard third act, which involves Lee’s damaged mother (Marin Ireland, excellent in her brief scenes) and a clunky scheme stumbled into by the incidental femme fatale. It’s a pulpy twist into upsetting territory that, for a single scene, left me breathless. But it’s followed by an unsatisfying and not particularly enlightening conclusion, with unanswered questions and uncertainty about whether the titular character learned anything.

My understanding of the book—which, in full disclosure, I have not read, but I trust my wife’s assessment—is that it’s told in first person by Eileen several decades after these events, giving substance to her inner life and perspective on her actions. Perhaps a similar framing device or internal dialogue may have shed additional light on the character, given more meaning to the ending, and enriched the film. At 98 minutes, the film is lean, superbly crafted in technical terms, and terrifically acted, though it feels not quite complete. It could have used more time inside this character’s messed-up mind, if not for answers, then at least more exposure to her unseemly behaviors and their patterns. McKenzie is compelling in the lead role, giving her finest performance since Leave No Trace (2018), and it’s easy to get lost in her screen time opposite Hathaway. But when the credits started to roll, I was left wanting more, albeit not in a good way.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review